Symmetry and Hermeneutics

What is written by inspiration must be read by inspiration.1

– wrf3

Natural methods do not produce supernatural results.

– wrf3

With my background in math and science, symmetry is a very important concept. Nature is full of symmetries. The conservation laws of energy, linear momentum, angular momentum, and charge correspond to time translation symmetry, space translation symmetry, rotational symmetry, and gauge symmetry, respectively. Is symmetry maintained in the supernatural world? That is, is symmetry maintained between the reading and writing of inspired works? Nature does break symmetry and perhaps it is the case that what is written by inspiration can be understood through natural means.

There are two striking examples in Scripture where symmetry must be preserved. As mentioned in this post on Dispensationalism, the first is Genesis 15:18:

On that day the LORD made a covenant with Abram, saying, “To your zera‘ I give this land, ...

zera‘ is ambiguous as to number, like the English word fish. Some English bibles translate it using the equally ambiguous "seed" or "offspring" but many, such as the NRSV, NASB, NIV, and NKJV use the plural "descendants". Not one uses the singular "descendent". The Septuagint, however, translates it as singular: "τῷ σπέρματί". Paul stresses this point in Galatians 3:16:

τῷ δὲ Ἀβραὰμ ἐρρέθησαν αἱ ἐπαγγελίαι καὶτῷ σπέρματι αὐτοῦ οὐ λέγει καὶ τοῖς σπέρμασιν ...

Now the promises were made to Abraham and to his descendent; it does not say, “And to descendants,” as of many; but it says, “And to your descendent,” that is, to one person, who is Christ.

Here, symmetry between the inspiration of the writing of scripture and the reading of scripture is maintained. Natural methods of reading Genesis 15:18 result in understanding "zera‘" as plural, instead of singular.

Another example of the importance of symmetry is seen in John 3:3 and 7, where Jesus tells Nicodemus "you must be born ἄνωθεν." ἄνωθεν can be understood several ways: again, anew, from the top, from above. Nicodemus' reply to Jesus shows that he understood it in a way that Jesus did not mean. Symmetry between inspiration and interpretation was broken.

There is a further symmetry between Paul's understanding of to whom the promises to Abraham were made and Jesus' statement to Nicodemus. Paul says that covenant with Abraham was not made to the "children of the flesh" (that is, the natural descendants) but to "the children of the promise." (Romans 9:6). He then uses Isaac and Jacob to illustrate who the children of the promise were. Isaac was born through divine intervention, for Sara was barren, and selected by divine choice, since Ishmael was firstborn. Both Esau and Jacob were born through divine intervention, for Rebekah was barren, but the promise went to Jacob through divine selection. In the same way, Jesus told Nicodemus that the children of the kingdom are born by divine intervention and divine selection.

[1] A search of DuckDuckGo, Google, and Bing turns up no sources for this quote. Yesterday, Grok attributed it to Joseph Smith, but a search of archive.org did not confirm this. Today, Grok attributed it to Ralph Waldo Emerson. But the referenced work did not contain these words.

Dispensationalism

Dispensationalists misunderstand scripture for the same reason Nicodemus misunderstood Jesus.

Read More...

Quote: Expulsion from Eden

And the LORD God said to Adam, "If you're going to hide from me,

you aren't going to do it in the comfort of my home."

– Gen 3:8, 24

On Limited Atonement

The Synod of Dort referred to the atonement in Articles 3, 5 and 6. In part, article 6 says:

... the sacrifice of Christ offered on the cross is [neither] deficient [n]or insufficient...2

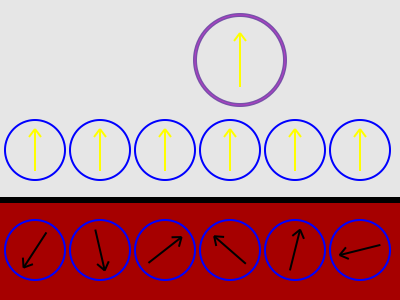

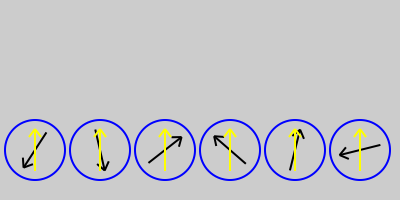

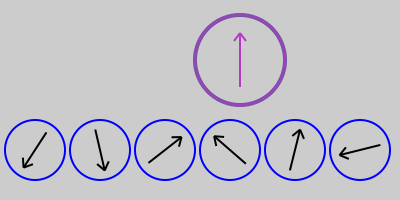

Proponents of limited atonement stress the sufficiency of the atonement but they overlook that their interpretation is deficient. These two pictures3 vividly illustrate how their "gospel" is deficient. There is sufficient water for everyone who is thirsty. But...

[1] Perhaps this explains other non-gospel gospels such as "Jesus is King" or "the kingdom of God is at hand." And if a limitarian says the gospel is "believe on the Lord Jesus Christ" follow up with the question, "believe what, exactly?"

[2] The "is not" outside of the quotation was distributed to the inside of the quotation.

[3] Courtesy of Grok.

More Rules of God Club

- The fourth rule of God club is that God is known by experience.1

- The fifth rule of God club is that only God can give you the experience of Himself.2

[1] Abraham had no scripture, no systematic theology, and no philosophy that we know of. Furthermore, he didn't need them. John 10:27; Heb 3:15

[2] Acts 22:6-9; John 3:3

Theodicy: Another Perspective

This same change of perspective is possible with the "problem" of evil (and divine hiddenness) which are two arguments employed for the non-existence of [a good] God.

The first step to the change of perspective is to remember that logic does not prove its axioms. It cannot, otherwise one is engaging in circular reasoning. The next step is to recall that logic neither adds to, nor subtracts from, the system described by the axioms. If it isn't "in" the axioms, it doesn't appear as a result; if it is "in" the axioms, it doesn't disappear from the result. Logic is a physical operation, not unlike a meat grinder. Beef in, hamburger out; pork in, ground pork out.

These first two steps should be without controversy. So should the third, but it's less familiar; namely, that nature does not impose on us the axioms that we choose. There are more axioms in "mind" space than there are in "meat" space2,3, and nature does not "tell" us which axioms we should use to describe it.

The switchover may come from the observation that the problem of evil and/or divine hiddenness are problems for some people and not for others. Jesus, for example, affirmed the existence of a good God in Luke 18:19 and denied a problem with hiddenness in his sermon on the mount [Matthew 5:8].

So if evil and hiddenness are problems, then the problem is inherent in the axioms; if they aren't problems, they aren't problems inherent in the axioms.4

Since nature doesn't tell us which axioms to choose, why do we choose the axioms we do? Are these "problems" just a mirror to our souls?

AddendumIt's gratifying to find someone coming to the same conclusion independently. In the coffee shop this morning I read the following and had to update this post.

Our passions infiltrate our intuitions. When in a bad mood, we read someone’s neutral look as a glare; in a good mood, we intuit the same look as interest. Social psychologists have played with the effect of emotions on social intuitions by manipulating the setting in which someone sees a face. Told a pictured man was a Gestapo leader, people will detect cruelty in his unsmiling face. Told he was an anti-Nazi hero, they will see kindness behind his caring eyes. Filmmakers have called this the “Kulechov effect,” after a Russian film director who similarly showed viewers an expressionless man. If first shown a bowl of hot soup, their intuition told them he was pensive. If shown a dead woman, they perceived him as sorrowful. If shown a girl playing, they said he seemed happy. The moral: our intuitions construe reality differently, depending on our assumptions. “We don’t see things as they are,” says the Talmud, “we see things as we are.” – "

Intuition", David G. Myers

[1] I usually make a "v" with my middle and index fingers and look at the dancer through the gap, starting at her feet and moving up until she changes direction. If she doesn't switch by the time I get to the waist, I move down and try again. Sometimes I have to vary with width of the gap. Blink several times and she goes back to the initial direction.

[2] This assumes that there is a difference between the two spaces. We certainly perceive that there is. But, as the dancer illustrates, we might not be looking at reality the right way.

[3] Non-Euclidean geometry is one well-known example of this.

[4] See "The Rules of God Club" for one set of axioms in which evil and hiddenness are not problems.

The Rules of God Club

The first three rules of God club:

- The first rule of God club is that you don't make the rules.

- The second rule of God club is that you can't intuit the rules.2

- The third rule of God club is that God doesn't play by the same rules.

[2] Prov 3:5, 1 Cor 2:6-16

Read More...

Fiat Lux & Anthropology

Before God said, "Let there be light," He said, "Let there be darkness" and "let there be chaos."

Dialog with an Atheist #4

@PhilosophieW is the straight man who has (unwittingly) set up the conversation for me (@stablecross) as the joker. The two atheists are @alancolquhoun1 and @theosib2. @theosib2 was featured in the third dialog.

@PhilosophieW: I would describe the perception of God as emotional and/or intuitive perception. I experience a deep connection, closeness, indeed love, often intertwined with a recognition of what is currently right or would be. Nothing extraordinary, and nothing that others do not also report.

@alancolquhoun1: My question asked for a characterisation of its perceptible qualities. I think I should (rationally) interpret your fourth failure to answer my question as either die [sic] to unwillingness or die [sic] to inability. Either way, we're no more enlightened than we were when you joined in.

@stablecross: Perhaps you missed my previous answer to your question. The perceptible qualities are those of sentience, by which you conclude that a being, other than yourself, has an “I”. And we know that one of those qualities isn’t physical construction.[2]

@alancolquhoun1: Sentience qua sentience is imperceptible.

@stablecross: Is your partner sentient?

@alancolquhoun1: Of course. But her sentence [sic] is not perceptible.

@stablecross: Then on what basis should anyone accept your claim when, to all appearances, she’s indistinguishable from a philosophical zombie?

Later, in another thread, @theosib2 wrote:

@theosib2: How else are you going to support something? If you claim something, you also need to provide SOME way to CHECK. "Trust me bro" is not an argument. And arguments grounded in unverified facts are unsound.

Seizing an opportunity I jumped in:

@stablecross: @alancolquhoun1 made the claim that his partner is sentient. I’ve asked why I should accept that she’s sentient and not a philosophical zombie. He hasn’t responded, despite prompts. Perhaps you can help him devise such a way so that it works on her, other animals, and machines?

@theosib2: I haven't ruled out that some humans might effectively be philosophical zombies. The majority of them are on Twitter and Facebook.

@stablecross: That’s irrelevant to the question posed. So what if you make that determination? Why should anyone else believe you?

@theosib2: It's relevant insofar as any kind of humor makes life better. I'm not an expert in philosophy of mind. All I have to go on is some study of neuroscience, which is probably not adequate on its own.

@stablecross: You don’t need Phil Mind or neuroscience. Everything you need to know you should have learned as part of your PhD. You simply cannot determine internal logical behavior by objective external measurement. You know this, because your only answer was “a lookup table.”

And so the conversation with @theosib2 dead ends where it did before, and with @alancolquhoun1 in the same place. The atheist makes claims to knowledge for which they can produce no objective support. Reason fails them when it comes to detection of mind. But they can't admit it, because that would remove one of the stabilizing legs of the chair on which atheist arguments sit.

[1] A third conversation is here, but it's based on philosophical stance instead of intelligence. The claim is that skepticism should be one's default position, which self-defeating. There has to be a ground of knowledge which just so happens to be the subjective "I". And that ties these conversations together.

[2] The Physical Ground of Logic.

Dialog with an Atheist #3

I prefer the academic definition of atheist: Belief that there are no gods.

I do not identify as an atheist.

I am a militant agnostic. I don't know, and you don't either.

@theosib2 and I have had numerous discussions about computer science and religion. In particular, we have gone back and forth about how we can test for 3rd party consciousness. It is absolutely impossible to objectively determine if something is conscious. The Inner Mind shows the physical reason why this is true. However, @theosib2 maintains this is not the case, even though I have pressed him to state what a function with this behavior is doing:

ξξ→ζ ξζ→ξ ζξ→ξ ζζ→ξ

Objectively, it's a lookup table. Objectively, it has no meaning and no purpose. It's just a swirl of meaningless objects. Subjectively, it does have meaning and purpose, but we can't decide what it is. It could be a NAND gate or a NOR gate. Arrange these gates into a computer program and we might be able to determine what it is doing by its overall behavior. But we have to be able to map its behavior into behavior that we recognize within ourselves.

With this as background, I responded to @theosib2:

“I’m conscious!”

“I don’t think so. You’re not carbon based.”

“I passed your Turing test, multiple times, when you couldn’t asses my form. I’m conscious, dammit.”

“I don’t know that you are. And you don’t, either.”

@theosib2 responded identically to "Victorian dad":

If only we could have a rigorous definition of consciousness. Then your comparison might be valid.

The endgame then played out as before:

Are you conscious?

Sometimes I wonder (with link to They Might Be Giants "Am I Awake?")

But only sometimes, right?

The atheist either has a problem with either knowing things that are subjectively known, or admitting the validity of subjective knowledge. Because if subjective knowledge is validly known, then demands for objective evidence for God are groundless. Because we have objective knowledge that mind is only known subjectively.

Quotes

The essence of Christianity is not doctrine any more than the essence of physics

is the formulas. Christianity is, first and foremost, hearing the music of heaven and

being so enthralled that you can't help but join in the dance.

-- wrf3

You can go from experience to reason about the experience.

But you cannot go from reason to experience.

No philosophical argument ever made anyone see the beauty

in a sunrise, taste the crispness of an apple, or cause a

sneeze.

So it is with God.

-- wrf3

The first quote was born after my morning walk/run while drying off afterward. I still had my AirPods in when a certain song by Fall Out Boy so captured my imagination that I started dancing in front of the mirror. It wasn't a pretty sight by any stretch of the imagination, but the Spirit blows where it will.

The second follows from the first, especially after reading "Apologetics Beyond Reason" by James. W. Sire, which greatly - and far more ably - expresses this than I ever could.

A Review of "Vital Grace"

Tom gets many things right. I told him on Sunday that I think that our church should make a class available with this book as the text. Having said that, now I'm going to "knife the baby" (not really. It's more of a deep exfoliation). Knowing me as he does, he expects no less because the purpose of a critical review is to make the next edition of the book even better.

Read More...

A Diplomatic Review of "A Boisterous Polemic"

[updated 11/15/2024, see footnote 6]

For whom did Christ die? A "5-point" Calvinist will answer, "for the elect only". A "4-point" or "moderate" Calvinist will answer "for everyone, but especially for the elect." "A Boisterously Reformed Polemic Against Limited Atonement", by Austin C. Brown, looks at the evidence for each answer and comes down on the side of the moderate Calvinist.

For the sake of brevity, I will use "5P" and "4P" to refer to the respective five point and four point positions.

My first observation, which should not be controversial, is that there is a typo in the Kindle version on page 190/191: "This happened to me twice. Once during the examination process to be become a deacon in the RPCNA and during my examination...". My remaining observations, save the penultimate, will be in areas where I think Brown could present a stronger argument. The next to last observation will be in the way of personal application.

Read More...

Critiquing Calvinism

... the Remonstrants were concerned about the teaching that God forces his grace on sinners irresistibly. [emphasis mine]

...

Bending the will of a fallible being by an omnipotent Being powerfully and unfailingly is not merely sweet persuasion. It is forcing one to change one’s mind against one’s will.

...

God changing our will invincibly in irresistible grace brings to mind phenomena such as hypnotism or brainwashing.

...

Note the striking contradiction—God will “overcome all resistance and make his influence irresistible,” and yet “irresistible grace never implies that God forces us to believe against our will.” No attempt is made in the article to reconcile these apparently contradictory assertions.

I will try to reconcile these allegedly contradictory assertions. The idea that God forces the spiritually dead to awaken to life in Christ is common in Arminian arguments. But it simply isn't what God does. "Aha!" moments, "Eureka!" moments rise from the recesses of our minds and present to us a new way of seeing, a new way of thinking, and that new thing is so obvious that we wonder why we never encountered it before. Of course we embrace it. Why would we not? It has positively transformed a part of our life.

Lemke asks:

Why would there be a need to persuade someone who had already been regenerated by irresistible enabling grace?

God works through His word: written, oral, or otherwise. He gives sight to the blind and hearing to the deaf (Ex. 4:11). He gives transforming inspiration. Regeneration and persuasion go hand in hand. He regenerates through persuasion and persuades through regeneration.

I am reminded of the scene in "The Wizard of Oz" when Dorothy opens the door of her house and sees Oz in color. Before then, everything was in black and white. The external change of location which brought color into her life is a parallel to the internal change that brings new sight to the Christian. What Dorothy saw on the outside the Christian sees on the inside.

[1] The "marriage" argument. It is argued that Christ died for His bride, the Church, to "sanctify it, having cleansed it." [Eph 5:25-27].

There is an inseparable unity between Christ's death for the church and his sanctifying and cleansing it. Those from whom he died he also sanctifies and cleanses. Since the world is not sanctified and cleansed, then it is obvious that Christ did not die for it.

– Edwin H. Palmer, "The Five Points of Calvinism".

I don't think this argument survives Isaiah 54:5:

For your Maker is your husband, the Lord of hosts is his name; ...

– NRSV

Which makes 1 Cor 7:15 all the more interesting.

Advent

There is a tragic scene in Ezekiel where the prophet sees the glory of the Lord leave the temple. It goes out the East Gate, departs Jerusalem and heads to the Mount of Olives, where it, presumably, ascends to heaven. It passes out of human experience and never returns to this temple. This divine visitation of God is called the “Shekhinah” Glory. “Shekhinah” - from the Hebrew word for “dwelling” - represents the visible presence of God among His people. When the Israelites were led out of Egypt from slavery to freedom, the Shekhinah glory led the way. When the Law was given to Israel at Mt. Sinai, the Shekhinah glory was there. After the Tabernacle was built, the Shekhinah glory resided in the most holy place above the ark of the covenant. When Solomon built the first temple, the Shekinah glory dwelt there. Rabbinic literature even states that the Shekinah glory sits at the right hand of God in heaven.

But in Ezekiel’s time it’s gone. In the intervening years, a new temple is built in Jerusalem, but there is no record of the presence of the glory of God. Until the night when a child who is the light of the world is born in Bethlehem. The night when the Shekinah glory is swaddled in rags and placed in a feeding trough. The night when everything changes and the world will never be the same again. And this is why we celebrate Advent!

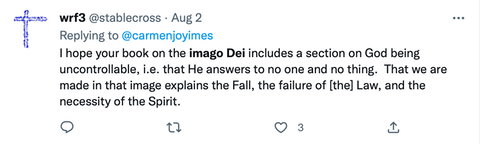

On the Image of God

Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”So God created humankind in his image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

– Genesis 1:26-27, NRSV

When we think of the "imago Dei", we typically think of things like:

- Self-awareness

- Rationality

- Creativity

- Infinity

- Universality

- Community (i.e. the Trinity)

- the Ideal. (Beauty, Quality, Utility, and Goodness all compare something to an ideal. Beauty is ideal appearance, quality is ideal construction, utility is ideal fitness for use, goodness is a general comparison to an ideal).

- Self-replication. God adopts us as sons and conforms us to the image of Christ.

Being made in this image explains the entire arc of redemption: the Fall, the failure of [the] Law, and the necessity of the Spirit.

This idea is clearly undeveloped, but given that I put it out on Twitter, I decided to publish this little bit.

On the Knowledge of God

[updated 11/21/2020 to change "all side" to "all sides"]

[updated 7/20/2022 to add quotes from Markides and Oppy]

I'm just this guy, you know?1 One of the possible recent mistakes I have made is getting involved with Twitter, in particular, with some of the apologists for theism and for atheism whose goal is to prove by reason that God does, or does not, exist. Over time, having examined both the arguments both for and against, I have come to the conclusion that neither side has any arguments that aren't in some way fundamentally flawed. One day, I will make this case in writing (I still have much more preparation to do first). Still, the failure of one argument doesn't automatically prove the opposite case. So the failure of the arguments on all sides does not mean that a good argument doesn't exist. It just means we haven't found it. Yet, once you see the structure of these arguments, their commonalities, and the problems with them, you begin to wonder if it isn't a hopeless enterprise in the first place. Hence my proposed "Spock-Stoddard Test" and "The Zeroth Commandment." To be sure, these are not based on rigorous proof, but merely on informed guesswork. But they encapsulate the notion that whether or not one believes or disbelieves in God is a logically free choice. It is primal. It is not entailed by other considerations. You either do, or you don't, for no other reason that you do, or you don't. Post-hoc rationalizations don't count.

When one is, as it were, the "lone voice crying in the desert" with an opinion that appears to be relatively rare, at least in the circles I run in, it's gratifying to find others who have come to the same conclusion. Clearly, group cohesion doesn't make my position true or false, but it does make it less lonely. Herewith are a few quotes that I've come across along the way.

He is not in the business of giving them arguments that will prove he has some derivative right to their attention; he is only inviting them to believe. This is the hard stone in the gracious peach of his Good News: salvation is not by works, be they physical, intellectual, moral, or spiritual; it is strictly by faith in him. ... Jesus obviously does not answer many questions from you or me. Which is why apologetics-the branch of theology that seeks to argue for the justifiability of God's words and deeds-is always such a questionable enterprise. Jesus just doesn't argue. ... He does not reach out to convince us; he simply stands there in all the attracting/repelling fullness of hisexousia and dares us to believe. -- Robert Farrar Capon. Parables of Judgment

Jesus did not, indeed, support His theism by argument; He did not provide in advance answers to the Kantian attack upon the theistic proofs. -- J. Gresham Machen,Christianity and Liberalism

Like probably nothing else, all authentic knowledge of God is participatory knowledge. I must say this directly and clearly because it is a very different way of knowing reality—and it should be the unique, open-horizoned gift of people of faith. But we ourselves have almost entirely lost this way of knowing, ever since the food fights of the Reformation and the rationalism of the Enlightenment, leading to fundamentalism on the Right and atheism or agnosticism on the Left. Neither of these know how to know! We have sacrificed our unique telescope for a very inadequate microscope.The Divine Dance

...

In other words, God (and uniquely the Trinity) cannot be known as we know any other object—such as a machine, an objective idea, or a tree—which we are able to “objectify.” We look at objects, and we judge them from a distance through our normal intelligence, parsing out their varying parts, separating this from that, presuming that to understand the parts is always to be able to understand the whole. But divine things can never be objectified in this way; they can only be “subjectified” by becoming one with them! When neither yourself nor the other is treated as a mere object, but both rest in an I-Thou of mutual admiration, you have spiritual knowing. Some of us call this contemplative knowing. -- Richard Rohr,

Reformed theology regards the existence of God as an entirely reasonable assumption, it does not claim the ability to demonstrate this by rational argumentation. Dr. Kuyper speaks as follows of the attempt to do this: “The attempt to prove God’s existence is either useless or unsuccessful. -- Louis Berkhof,Systematic Theology

Today, it is generally agreed that there can be no logical proof either way for the existence of God, and that this is purely a matter of faith. -- Marcus Weeks,Philosophy in Minutes

But the way to know God, Father Maximos would say repeatedly, is neither through philosophy nor through experimental science but through systematic methods of spiritual practice that could open us up to the Grace of the Holy Spirit. Only then can we have a taste of the Divine, a firsthand, experiential knowledge of the Creator. -- Kyriacos C. Markides,The Mountain of Silence

I think that such theists and atheists are mistaken. While they may be entirely within their rights to suppose that the arguments that they defend aresound, I do not think that they have any reason to suppose that their arguments are rationally compelling... -- Graham Oppy, Arguing About Gods

One final quote is appropriate:

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God. -- Matthew 5:8, NRSV

[1] Said of Zaphod Beeblebrox, "The Restaurant and the End of the Universe"

Evidence for Christianity

At some point, it pays to stop beating your head against a wall and see if a fresh approach doesn't yield a new way to look at the problem.

The theory of computation shows that computation is certain behaviors on meaningless symbols (cf. the Lambda Calculus). We know, from the Lambda Calculus, how to derive logic. Once we have logic, we can derive meaning. From there, we can derive math, morality, and everything else for a human level intelligence. One can replace the meaningless symbols with physical atoms and show how neurons implement computation. And we know from computability theory, that how the device is implemented isn't what's important - it's the behavior.

We know that human level sentient creatures have a sense of self. It is something we are directly aware of, but outside observers cannot measure it objectively. Our thoughts, our ego, are "inside" the swirling atoms in our brains. An outside observer can only see the behavior caused by the swirl of atoms. Certainly, we can hook electrodes up to brains and measure electrical activity. But we cannot know what that activity corresponds to internally, unless the test subject tells us. It is only because we share common brain structures that we can try to predict which activity has what meaning in others.

The swirl of atoms in our brains, the repeated combination and selection of meaningless symbols, is a microcosm of the swirling of atoms in the universe. If our brains are localized intelligence, the case can be made that swirl of atoms in the universe is a global intelligence. But this is a subjective argument. This is why the Turing Test is conducted where an observer cannot see the subject. Seeing the human form biases us to conclude human intelligence. But for a non-human form, an observer has to recognize sentience from behavior. Why might that not be the case?

First, because there is a lot of randomness in the behavior of the universe and it is a common idea that randomness is ateleological. It lacks meaning and purpose. Unfortunately, this philosophical stance is without merit, since randomness can be used to achieve determined ends. The fact of randomness simply isn't enough to move the needle between purpose/purposelessness and meaning/meaninglessness. One could argue that human intelligence contains a great deal of randomness. But an observer looking on the outside cannot objectively see which is the case.

Second, because the behavior of the universe doesn't always comport with our desires. Our standards of good and evil are not the universe's standards of good and evil. If one holds to an objective morality, one will miss the possible sentience of someone who behaves very differently from ourselves.

Third, we want to think that there is only one objectively right way to view the universe. But the universe doesn't make that easy. We have the built-in knowledge of infinity (an endless and therefore unmeasurable process). There is no consensus whether infinity is "real" or "actual" and, since we can't measure it, I don't think consensus will ever be achieved. There is also the question of whether matter produces and moves the mind or mind produces and moves matter. Neither side has achieved consensus.

Into this mix comes Christianity which states that there is an extra-human intelligence "inside" the existence and motion of the universe, who has a sense of right and wrong that is different from ours, where what has been made is a strong indication of that sentience, and who calls people to itself. Because sentience is a subjective measurement, it must be made on faith - which is one of the bedrock tenets of Christianity. This picture of local intelligences inside a bigger intelligence is consistent with "in Him we live and move and have our being." Yet in spite of this connectedness, we remain disconnected, not recognizing our state. Which is yet another teaching of Christianity.

Much more can, and must, be said. But the immateriality and incommensurability of infinity; the subjectivity of sentience and morality; and the ability to build thinking things out of dirt are all a part of both Christianity and natural theology.

On Self

While I agree with this sentiment (after all, Psalm 57:1 says that God has wings), Dr. Tuggy has also used this idea to defend Unitarianism. More specifically, Dr. Tuggy lists 20 self-evident principles that he uses to guide his reading of Scripture.

While this post is not meant to focus on the debate between Trinitarians and Unitarians, I do want to use Dr. Tuggy's tweet as a springboard to consider if his "self-evident" truths are universally self-evident. I think there is reason to believe that they may not be.

Not long after we are born, we start to distinguish ourselves from our surroundings. We can feel a difference between ourselves and our environment. Place your hand on a table and run your finger from your hand to the table and notice the boundary your senses tell you is there. Look at your hand and notice the boundary between your hand and the table. Lift your hand from the table and notice that your hand moves but the table does not. Look in a mirror and notice the difference between you and your environment. All of these sense data tells us that we are distinct self-contained objects.

But our senses also tell us that the table on which our hand rests is solid. In reality, the table is mostly empty space. What we perceive as solidness is the repulsion of the electric field from the electrons in the table against the like-charged electrons in our hand. If we perceive a location for ourselves, we generally place it inside our skulls. To nature, there is no inside. Billions of neutrinos pass through a square centimeter every second. The experimental particle physicist, Tommaso Dorigo, speculates:

... a few energetic muons are crossing your brain every second, possibly activating some of your neurons by the released energy. Is that a source of apparently untriggered thoughts? Maybe.

4gravitons writes:

This is Quantum Field Theory, the universe of ripples. Democritus said that in truth there are only atoms and the void, but he was wrong. There are no atoms. There is only the void. It ripples and shimmers, and each of us lives as a collection of whirlpools, skimming the surface, seeming concrete and real and vital…until the ripples dissolve, and a new pattern comes.

From a physical view, what we are, are ripples in the quantum pond, with our "selves" limited to local interaction by an inverse square law. From a Biblical view,

‘In him we live and move and have our being’

— Acts 17:28, NRSV

I suspect there is no "inverse square law" with spirit so what separates us from one another is a... mystery.1

[1] Almost immediately after hitting "publish", I started kicking myself. Scripture says what separates us, from God and from each other:

Rather, your iniquities have been barriers between you and your God ...

— Isa. 59:2, NRSV

On Limited Atonement

The scope and application of the Atonement is an issue, it seems, that is a fairly modern development. Up until the 9th century, the writings of the Church fathers showed agreement that the scope of the atonement was universal -- for everyone -- but that its effect was limited to those who believe[1]. Many (but not all) Calvinists affirm that the Atonement is limited in scope and limited in effect. And this is clearly important to some Presbyterians.

John McLeod Campbell was a Scottish minister and highly regarded Reform theologian. A number of his writings are still available on Amazon. He allegedly disagreed with the Westminster Confession of Faith regarding the doctrine of limited atonement by teaching that the Atonement was unlimited in scope, was charged with heresy, and was removed from the ministry. Campbell might have been able to raise a defense if he had had a copy of Grudem's Systematic Theology[2], where Grudem writes:

Finally, we may ask why this matter is so important after all. Although Reformed people have sometimes made belief in particular redemption a test of doctrinal orthodoxy, it would be healthy to realize that Scripture itself never singles this out as a doctrine of major importance, nor does it once make it the subject of any explicit theological discussion. Our knowledge of the issue comes only from incidental references to it in passages whose concern is with other doctrinal or practical matters.

Alas for Campbell, he was born some 180 years too soon. To add insult to excommunication, as mentioned in the previous post on limited atonement, the Confession was written by a committee. And the committee consisted of members who held to both interpretations of the scope of the Atonement. The wording of section VI of chapter 3 was such that both sides could sign the confession[see also 3]. Section 3.VI of Westminster states:

As God has appointed the elect unto glory, so has He, by the eternal and most free purpose of His will, foreordained all the means thereunto.[12] Wherefore, they who are elected, being fallen in Adam, are redeemed by Christ,[13] are effectually called unto faith in Christ by His Spirit working in due season, are justified, adopted, sanctified,[14] and kept by His power, through faith, unto salvation.[15] Neither are any other redeemed by Christ, effectually called, justified, adopted, sanctified, and saved, but the elect only.[16]

I happen to agree with this. It says:

- God has ordained the means of salvation

- Those whom God has foreordained for salvation will be saved.

- Only those foreordained for salvation will be saved.

In this section, then, we are taught, ... ThatChrist died exclusively for the elect, and purchased redemption for them alone; in other words, that Christ made atonement only for the elect, and that in no sense did he die for the rest of the race. Our Confession first asserts, positively, that the elect are redeemed by Christ; and then, negatively, that none other are redeemed by Christ but the elect only.

So while I agree with 3.VI, I don't agree with this commentary!

The commentary wonders how anyone could read 3.VI any other way:

If this does not affirm the doctrine of particular redemption, or of a limited atonement, we know not what language could express that doctrine more explicitly.

I would reply that if you don't know what language would be more clear, perhaps you should talk to those who find the language opaque. Specifically adding, "Christ died only for the elect" would make the section more clear. Or "the atonement precedes God's call and guarantees election". More on this last point later.

The positive case for universal atonement can be made from two passages of scripture: Romans 5:6 and 3:23-26:

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for theungodly.

-- Romans 5:6, NRSV

... sinceall have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

-- Romans 3:23-26, NRSV

Grudem nowhere references Romans 5:6, and Romans 3:23-26 are not found in his discussion on the extent of the atonement. Berkhof [4] references neither. To me, that's a telling omission in any argument attempting to limit the scope of the atonement.

So where does the doctrine of limited atonement come from? The argument from Berkhof will be examined.

In VI.3.b, Berkhof claims that “Scripture repeatedly qualifies those for whom Christ laid down His life in such a way as to point to a very definite limitation” and points to John 10:11 & 15 as the primary proof texts. "I lay down my life for the sheep" is read as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep." Now this is an odd way to read this statement. If I say, "I give money to my children," it in no way precludes my giving money to strangers. Why Jesus' words are read this way is a mystery, but I can make two guesses.

First, the declarative statement is read as a conditional: "If I lay down my life then it is for a sheep." If read this way, then simple logic shows that this is equivalent to "if not a sheep then I do not lay down my life." [6] Voila! Limited atonement. But you can't validly turn a declarative statement into a conditional.

Second, the passage is read as if it is the act of giving money that makes someone a child. The payment is taken from the outstretched hand, the legal paperwork is completed, and the person actually becomes a part of the family. The offer guarantees the reception. But that cannot be found in this verse. It has to be found elsewhere. Berkhof makes the attempt to show this and his arguments will be addressed in turn.

Reading John as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep" has a cascade effect throughout scripture. The following passages would have to be changed. The changes are in underlined italics.

The next day he saw Jesus coming toward him and declared, “Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of theelect in the world!”

-- John 1:29, NRSV

and he is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of theelect in the whole world.

-- 1 John 2:2, NRSV

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for theelect ungodly.

-- Rom 5:6, NRSV

For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. And he died for allof the elect, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them.

-- 2 Cor. 5:14-15, NRSV

This is not an exhaustive list of the changes that would have to be made. Yet changes of this type are what is argued. In VI.4.a, Berkhof writes:

The objection based on these passages proceeds on the unwarranted assumption that the word “world” as used in them means “all the individuals that constitute the human race.” If this were not so, the objection based on them would have no point. But it is perfectly evident from Scripture that the term “world” has a variety of meanings...

Granted. But at some point the addition of epicycle upon epicycle turns the perspicuity of Scripture on its head. Eventually we have to say, "Enough!". Grudem as much admits this when he writes:

On the other hand, the sentence, “Christ died for all people,” is true if it means, “Christ died to make salvation available to all people” or if it means, “Christ died to bring the free offer of the gospel to all people.” In fact, this is the kind of language Scripture itself uses in passages like John 6:51; 1 Timothy 2:6; and 1 John 2:2. It really seems to be only nit-picking that creates controversies and useless disputes when Reformed people insist on being such purists in their speech that they object any time someone says that “Christ died for all people.” There are certainly acceptable ways of understanding that sentence that areconsistent with the speech of the scriptural authors themselves.

Having dealt with VI.3.b and VI.4.a, we next look at VI.3.c, where Berkhof writes:

The sacrificial work of Christ and His intercessory work are simply two different aspects of His atoning work, and therefore the scope of the one can be no wider than that of the other. ... Why should He limit His intercessory prayer, if He had actually paid the price for all?

Note that no Scripture is referenced to support the claim "the scope of atonement can be no wider than the scope of His intercessory prayer." Instead, the proposition is "supported" by a rhetorical question. But the answer is really simple. In John 17, Jesus prays that He would be glorified (17:1 [5]), that His disciples would be protected and united (v. 11). For those who are not yet His disciples, He calls out “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest.” [Mt. 11:28] and "Follow me" [Lk 9:59]. The Psalmist wrote:

Your steadfast love, O LORD, extends to the heavens, your faithfulness to the clouds. Your righteousness is like the mighty mountains, your judgments are like the great deep; you save humans and animals alike, O LORD. How precious is your steadfast love, O God! All people may take refuge in the shadow of your wings.

-- Psalms 36:5-7, NRSV

Note the universal scope of God's love in the Psalm. All may take refuge. 2 Cor. 5:14-15, which has already been cited, likewise shows universal scope but limited effect:

For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. Andhe died for all, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them.

If the atonement was only for the elect, it should have been "all," not "those who live" and "will live" not "might live".

In VI.3.d, a straw man argument against a slippery slope is made:

It should also be noted that the doctrine that Christ died for the purpose of saving all men, logically leads to absolute universalism, that is, to the doctrine that all men are actually saved.

Christ died that all might be saved and creation re-made, not that all will be saved. It must not be forgotten that because of the atonement there will be a "new heavens and a new earth". [2 Peter 3:13]

VI.3.e tries to make the case that the offer guarantees reception. Berkhof writes:

... it should be pointed out that there is an inseparable connection between the purchase and the actual bestowal of salvation.

He cites six passages to support this claim: Matt. 18:11; Rom. 5:10; II Cor. 5:21; Gal. 1:4; 3:13; and Eph. 1:7. The problem is that these passages don't speak to the scope of the atonement! Someone who holds to limited atonement will read these passages without discomfort, and someone who holds to unlimited atonement will also read these passages without discomfort! Try it. Read the verses. Switch sides. Read them again. If you find a problem, check your assumptions.

VI.3.f conflates two issues. For the first, Berkhof writes:

And if the assertion be made that the design of God and of Christ was evidently conditional, contingent on the faith and obedience of man...

This is a straw argument. Election is conditional, based on the sovereign choice of God. "For he says to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.” So it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who shows mercy" [Rom 9:15-16].

Berkhof them claims:

... the Bible clearly teaches that Christ by His death purchased faith, repentance, and all the other effects of the work of the Holy Spirit, for His people.

He's repeating that which he is trying to prove. At this point, the argument becomes circular. Once again, the passages offered in support of this position: Rom. 2:4; Gal. 3:13,14; Eph. 1:3,4; 2:8; Phil. 1:29; and II Tim. 3:5,6 simply do not bear the weight of his case. They do not speak to the scope of the atonement. A possible explicit counter-example to Berkhof's might be 2 Peter 2:1:

But false prophets also arose among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you, who will secretly bring in destructive opinions. They will evendeny the Master who bought them—bringing swift destruction on themselves.

This who hold to limited atonement might argue that "denying the Master who bought them" is equivalent to Peter's denial of Christ at His trial. But this is Peter writing about these false teachers and there is no hint of recognition that their denial is like his denial. One thinks of Hebrews 10:29. Perhaps the only question asked of everyone at the final judgement is, "what did you do with the blood of My Son?" Nevertheless, both sides have their explanations so this can't be considered conclusive.

Having looked at the positive case and found it wanting, Berkhof examines four objections to the doctrine of limited atonement. Reviewing the first three, VI.4.a, VI.4.b, and VI.4.c, would be redundant. But VI.4.d is important. Berkhof writes:

Finally, there is an objection derived from the bona fide offer of salvation

That is, under limited atonement, one cannot truthfully say, "Christ died for your sins." Nor, as Berkhof claims, is “the atoning work of Christ as in itself sufficient for the redemption of all men”. For it is sufficient only for the elect.

You cannot say, "well, the offer is only for the elect but, since we don't know who is and isn't elect, we can make the offer." For those who hold to the "third use of the Law," this is ignorant of what the Law says. Leviticus, chapter 4, deals with the atonement that must be made for sins committed in ignorance. "Ignorance is no excuse" is a Biblical principle. We cannot use ignorance as an excuse to do good. Under limited atonement, there is no bona fide offer of salvation to the non-elect.

[1] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 61: "Important to note here is the fact that the question of the extent of the atonement had not been argued previously, and Gottschalk’s views are important 'because it is the first extant articulation of a definite atonement in church history.'"

[2] Systematic Theology, Wayne Grudem, 1994

[3] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 23: "... some at Dort and Westminster differed over the extent question and the final canons reflect deliberate ambiguity to allow both groups to affirm and sign the canons."

[4] Systematic Theology, Louis Berkhof, 1941

[5] Note that in John 17:2, Jesus claims that He has authority over "all people". But, clearly, His authority extends only to the elect, since the atonement extends only to the elect. If the Reformed want to be consistent, then they have to actually be consistent!

[6] The contrapositive of a conditional statement is logically equivalent to the conditional statement.

On Formal Proofs For/Against God

[Updated 2/2/2024]

Over on Ed Feser's blog, is another attempt, in a never-ending series of attempts, to formally prove the existence of God. [1] I was playing devil's advocate by taking the position that the answer to Feser's question is a resounding "no" by providing counter-arguments to their arguments. [2] [3]

"Talmid" made the statement:

You can defend that the arguments fail...

This is where the light came on.

Nobody would say of the proof of the Pythagorean theorem, or of the non-existence of a largest prime number, that "the arguments fail." That isn't how proofs work. If a proof fails, it's because of one of two reasons. Either a premise is denied, or there is a mistake in the mechanical procedure of constructing the proof. When you read these proofs of God's existence (or non-existence), at some point you come to a step in the proof where it looks like the next logical step was taken by coin-flip, instead of logical necessity. This is evidence of the presence of an unstated premise.

Find the unstated premises. Don't let your common sense get in the way. [4] If the argument assumes that things have a beginning, question it. Why must history be linear and not, say, circular? [5] Why can't something come from nothing? That may defy common sense, but it's still an assumption.

Now, suppose that in an argument for or against God that there are five premises. If the premises are independent of each other (and they should be, otherwise one of them isn't a premise), and each premise has a 50-50 chance of being correct, then the proof has a one in thirty-two chance of being correct. Those aren't great odds.

An immediate response to this would be, "but Euclidean geometry has five premises, and it's correct! So why not an argument for/against God with the same number of premises?" The answer is simple. We can measure the results of Euclidean geometry with a ruler and a protractor. While it's against the rules to construct something in Euclidean geometry with anything other than a straightedge and a compass, it isn't against the rules to check the result with measuring devices. And for non-Euclidean geometry, which is used in Relativity, we can measure it against the curvature of light around stars and the gravitational waves produced by merging black holes.

But we can't measure God, at least the non-physical God as God is normally conceived[6].

If that's the case, then it doesn't make sense to argue for/against the existence of God by any means other than "assume God does/does not exist". That gives a one in two chance of being right, as opposed to one in four, one in eight, ... one in 2^(number of premises).

If the premise "God does/does not exist" leads to a contradiction then, assuming the principle of (non)contradiction, the premise is falsified. I suspect, but cannot prove, that both systems are logically consistent. If this is so, then the search for God by formal argument is futile.

[Update:]

It seems to me that if the search for God by formal argument is futile, then the choice of axiom - God does/does not exist - is a logically free choice. And if it's a choice that you are not logically compelled to make, then it comes down to desire. [7]

[1] Can a Thomist Reason to God a priori?

[2] Commenting as "wrf3".

[3] I've informally taken this position here, here, here, and here.

[4] One unstated premise is usually, "common sense is a reliable guide to true explanations." It isn't. Relativity, and Quantum Mechanics, defy "common sense". Quantum Mechanics, for example, uses negative probabilities in the equations of quantum behavior. What's a negative probability? What's a "-20% chance of rain"? Yet we are forced by experiment to describe Nature this way.

[5] Quantum Mechanics also defies our common sense on causation, cf. "Quantum Mischief".

[6] Sentience/consciousness/the inner mind cannot be objectively measured. See The Inner Mind.

[7] For the desire to be fulfilled, God must then fulfill it. You can't tickle yourself. If you want to experience tickling, you must be tickled by someone else. If you want to experience God, then God must reveal Himself.

On Romans 7:7 and 2:14-15

When Gentiles, who do not possess the law, do instinctively what the law requires, these, though not having the law, are a law to themselves. They show that what the law requires is written on their hearts, to which their own conscience also bears witness; and their conflicting thoughts will accuse or perhaps excuse them...

That is, Gentiles have an intrinsic, if imperfect, knowledge of what God's law requires. In this verse in the original Greek, notice how Paul switches between "a law" and "the law," i.e. the Mosaic Law.1

But in chapter 7, Paul says that he would not have known what sin was if the Mosaic Law hadn't told him:

What then should we say? That the law is sin? By no means! Yet, if it had not been for the law, I would not have known sin. I would not have known what it is to covet if the law had not said, “You shall not covet.”

That's surprising. Shouldn't Jews have at least the same basic knowledge of right and wrong, just like Gentiles?

I pondered this on and off for months, getting nowhere. During a discussion last week, someone made a statement similar to Paul's: "I wouldn't know adultery was wrong unless the Mosaic Law told me." And the answer fell into place. "Then you don't know what love is," I replied, "because love does no harm to a neighbor, and your spouse is your closest neighbor."

I think the resolution to the dilemma between verses 2:14-15 and 7:7 is that Paul is letting on that he was a hard, loveless man prior to the Damascus Road. And because he had no love, he needed the Law to show him how to live in his society. That makes the love passage in 1 Cor. 13 even more impressive, as it would then have come solely from his Damascus change, where he came under the New Covenant and God replaced his "heart of stone" with a "heart of flesh".

[1] For an example of this, see Another Short Conversation.

The Parables of Exclusion

The "Wise and Foolish Virgins" (Matthew 25:1-13), "I never knew you" (Matthew 7:21-23), "The Rich Man" (Mark 10:17-22).

We normally take these stories to mean that there comes a time when the door will be shut, the party will begin, those who are inside will rejoice. And while that is true, I'm no longer sure that that's what Jesus is really saying.

I don't remember all of the details, but in Men's Bible Study a few weeks ago the question was asked, "what would you do if Jesus said to you, 'I never knew you?'" The first answer was, "Nothing. There's nothing you can do."

I had an epiphany and said, "On the contrary. I would say to Him, 'In November, 1978, at two in the morning, you called me and I have followed ever since. You invited me to this party. Now, it's your party, but if you want me to leave you're going to have to summon your bouncers."

In the same way, the "foolish" virgins should either have followed those who had lamps, or returned to the party once they had gotten more oil and pounded on the door until someone opened, even if it was the next day. It isn't as if that party will end.

I think we need to read these stories in light of the Canaanite woman who asked Jesus to heal her daughter (Mt 15:21-28). She didn't give up, she didn't let go.

In the single-minded pursuit of God, you mustn't quit.

The Prodigal God

It's not a bad book. It provides some interesting insight into the story of the two sons and how the two sons are really us. I consider it an interesting companion to Capon's Kingdom, Grace, Judgement.

But, given my high expectations, and the five star rating currently on Amazon, the book was almost completely ruined by this one passage:

...the prerequisite for receiving the grace of God is to know you need it.

There is no more wrong statement than this. There is no prerequisite for receiving God's grace, because it is God's grace that opens your eyes to your need in the first place. Presbyterians are funny creatures. They hold to the tenets of Calvinism that says that God's grace is irresistible and that there is nothing man can do to merit grace, then say things like this.

A lesser peeve is that Keller wants to redefine what "sin" means. He writes,

... sin is not just breaking the rules, it is putting yourself in the place of God as Savior, Lord, and Judge...

This fails to make this case, since the very first rule (at least as given to Moses) is "You shall have no other gods before me," and the behavior described by Keller breaks this rule.

Finally, Keller agrees with those who hear Jesus' cry from the cross, "Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?", and conclude that in that moment of pain and darkness that His Father turned His back on His Son and abandoned Him:

He was expelled from the presence of the Father, he was thrust into the darkness, the uttermost despair of spiritual alienation...

I am forever grateful to my mentor, Mike Baer, who once related the wise words of a nun who said, "I'm willing to be the second person God ever forsook." Because God never forsakes His people -- most of all the One who dwells in the "bosom of the Father" (John 1:18). Jesus couldn't say, "go read Psalm 22". The text didn't have those divisions then. By saying the first line of Psalm 22, Jesus was pointing to the end of the Psalm, which tells of rescue and victory.

Am I being too hard on Keller? Possibly. But with his stature comes greater responsibility.

On the Undecidability of Materialism vs. Idealism

According to Douglas Hofstadter1:

What is a self, and how can a self come out of the stuff that is as selfless as a stone or a puddle? What is an "I" and why are such things found (at least so far) only in association with, as poet Russell Edison once wonderfully phrased it, "teetering bulbs of dread and dream" .... The self, such as it is, arises solely because of a special type of swirly, tangled pattern among the meaningless symbols. ... there are still quite a few philosophers, scientists, and so forth who believe that patterns of symbols per se ... never have meaning on their own, but that meaning instead, in some most mysterious manner, springs only from the organic chemistry, or perhaps the quantum mechanics, of processes that take place in carbon-based biological brains. ... I have no patience with this parochial, bio-chauvinist view...

According to the Bible2:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. ... And God said, "Let there be light"; and there was light.

I believe that computability theory, in particular, the lambda calculus, can shed some light on this problem.

In 1936, three distinct formal approaches to computability were proposed: Turing’s Turing machines, Kleene’s recursive function theory (based on Hilbert’s work from 1925) and Church’s λ calculus. Each is well defined in terms of a simple set of primitive operations and a simple set of rules for structuring operations; most important, each has a proof theory.3

All the above approaches have been shown formally to be equivalent to each other and also to generalized von Neumann machines – digital computers. This implies that a result from one system will have equivalent results in equivalent systems and that any system may be used to model any other system. In particular, any results will apply to digital computer languages and any of these systems may be used to describe computer languages. Contrariwise, computer languages may be used to describe and hence implement any of these systems. Church hypothesized that all descriptions of computability are equivalent. While Church’s thesis cannot be proved formally, every subsequent description of computability has been proved to be equivalent to existing descriptions.

It should be without controversy that if a computer can do something then a human can also do the same thing, at least in theory. In practice, the computer may have more effective storage and be much faster in taking steps than a human. I could calculate one million digits of 𝜋, or find the first ten thousand prime numbers, but I have better things to do with my time. It is with controversy that a human can do things that a computer, in theory, cannot do.4 In any case, we don't need to establish this latter equivalence to see something important.

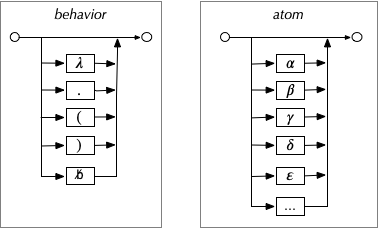

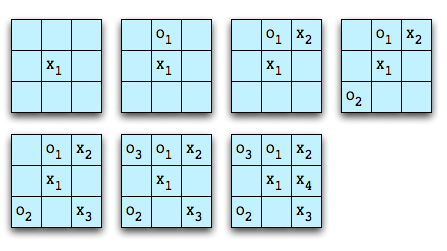

The lambda calculus is typically presented in two parts. Lambda expressions and the lambda expression evaluator:

![]()

One way to understand this is that lambda expressions represent software and the lambda evaluator represents hardware. This is a common view, as our computers (hardware) run programs (software). But this distinction between software and hardware, while economical and convenient, is an arbitrary distinction which hides a deep truth.

Looking first at 𝜆 expressions, they are defined by two kinds of objects. The first set of five arbitrary symbols: 𝜆 . ( ) and space represent simple behaviors. It isn't necessary at this level of detail to fully specify what those behaviors are, but they represent the "swirly, tangled" patterns posited by Hofstadter. The next set of symbols are meaningless. They represent arbitrary objects, called atoms. Here, they are characters are on a screen. They can just as well be actual atoms: hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and so on.

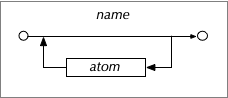

The only requirement for atoms is that they can be "strung together" to make more objects, here called names (naming is hard).

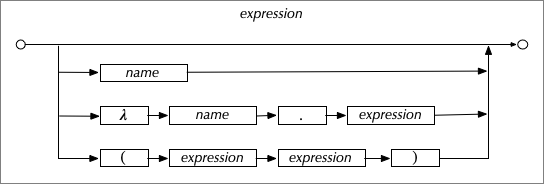

With these components, a lambda expression is defined as:

Note that a lambda expression is recursive, that is, a lambda expression can contain a lambda expression which can contain a lambda expression, .... This will become important in a future post when we consider the impact of infinity on worldviews.

With this simple notation, we can write any computer program. Nobody in their right mind would want to, because this notation is so tedious to use. But by careful arrangement of these symbols we can get memory, meaning, truth, programs that play chess, prove theorems, distinguish between cats and dogs.

Given this definition of lambda expressions, and the cursory explanation of the lambda expression evaluator (again, see [3] for details), the first key insight is that the lambda expression evaluator can be written as lambda expressions. Everything is software, description, word. This includes the rules for computation, the rules for physics, and perhaps even the rules for creating the universe.

But the second key insight is that the lambda evaluator can be expressed purely as hardware. Paul Graham shows how to implement a Lisp evaluator (which is based on lambda expressions) in Lisp. And since this evaluator runs on a computer, and computers are logic gates, then lambda expressions are all hardware. With the right wiring, not only can lambda expressions be evaluated, they can be generated. We can (and do) argue about how the wiring in the human brain came to be the way that it is, but that doesn't obscure the fact that the program is the wiring, the wiring is the program. That we can modify our wiring/programming, and therefore our programming/wiring, keeps life interesting.

Therefore, it seems that materialism and idealism remain in a stalemate as to which is more fundamental. It might be that dualism is true, but I think that by considering infinity that dualism can be ruled out as an option, as I hope to show in a future post.

[1] Gödel. Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid, Twentieth-anniversary Edition; Douglas R. Hofstadter; pg. P-2 & P-3

[2] The Bible, New Revised Standard Version, John 1:1, Genesis 1:3

[3] An Introduction to Functional Programming Through Lambda Calculus, Greg Michaelson

[4] This would require a behavior we cannot observe; a behavior we can't describe; or a behavior we can't duplicate. If we can't observe it, how do we know it's a behavior? A behavior that we can't describe would mean that nature is not self-describing. That seems impossible given the flexibility of description, but who knows?. There might be behaviors we can't duplicate, but that would mean that nature behaves inside human brains like it can behave nowhere else. But there just aren't examples of local violation of general covariance, except by special pleading.

Update 9/30/20

In The Emperor's New Mind, Richard Penrose muses:How can concrete reality become abstract and mathematical? This is perhaps the other side of the coin to the question of how abstract mathematical concepts can achieve an almost concrete reality in Plato’s world. Perhaps, in some sense, the two worlds are actually the same?

Note the unexamined bias. Why not ask, "how can the abstract and mathematical become concrete?" In any case, they can't be the same, since infinity is different in both.

Epistemology & Hitchens

... Reformed theology regards the existence of God as an entirely reasonable assumption, it does not claim the ability to demonstrate this by rational argumentation. Dr. Kuyper speaks as follows of the attempt to do this: “The attempt to prove God’s existence is either useless or unsuccessful."

Let me now attempt to put some theory behind these musings.

A Twitterer attempted to take Christopher Hitchens to task for his statement:

What can be asserted without proof can be dismissed without proof.

Hitchens isn't wrong, but his statement is incomplete. The corrected version should read:

What can be asserted without proof can be accepted or dismissed without proof.

Why is this so? Because reason has to start somewhere. It has to hold that some fundamental, foundational, things are true simply because they are true. They are the first stepping stone on what may be a long journey.

It may be that an axiom results in a system that conflicts with empirical measurement. In that case, the axiom can be rejected (or the measurement questioned). It may be that the axiom agrees with empirical measurement. In that case, it can continue to be provisionally accepted for as long as no other disconfirming empirical measurement is found. Note that empirical agreement with one axiom does not rule out other axioms that have the same empirical agreement.

It may be that an axiom conflicts with other axioms or statements derived from those axioms. In that case, something has to give. Knowing what has to give can be problematic.

But it may also be the case, thanks to Gödel and the universe, that we can never fully explore the consequences of the axiom either logically or empirically. In that case, you are free to accept it or reject it.

I submit for your consideration that the axiom of "God" is in the latter category. You are free to accept or reject as you will. It may be one of the few truly free choices you get to make in life. In thousands of years there has been no successful logical proof of God's existence, nor has there been a successful logical proof of God's non-existence. Neither is there any generally accepted empirical proof either way. Note that I put self-reflection in the category of empirical proof.

But this means I also have to finish my examination of the Warren-Flew debate to show why Flew ultimately failed.

Warren-Flew Debate, Part 2

In my previous post, I lamented that neither side addressed what it means to know. Still, Flew made some observations which deserve comment.

On Knowledge

That is to say we have to start from and with our common sense and our scientific knowledge of the universe around us.

Yes, we all have to start somewhere. But we need to establish criteria on how we know we've arrived. With common sense, Flew fails to establish whether the majority view (theism) or the minority view (atheism) is the "common" one. One can do an internet search for "humans hardwired religion" and see the arguments for and against. The argument against says that humans are hardwired for pattern recognition, but this misses the point. After recognizing patterns, we seek teleology. And we are wired for teleology - we have to be - but atheists suppress this aspect of being.

As to scientific knowledge, scientific knowledge is incomplete and sometimes wrong. This is not to disparage science; it's just the nature of the thing. Too, scientific knowledge contains descriptions based on empirical induction, and descriptions from empirical induction are probabilistic. That means that there is some point where we consider a probability high enough to be trustworthy - whether it's 50.1%, 75%, or 99.9999%. And this leads to the necessity of what it means to trust Nature and whether or not Nature is trustworthy. Note that the same considerations apply to questions about God.

Of equal importance is the trustworthiness of our intuitions. Feynman gives an idea of inability of intuition to grasp quantum mechanics. In his hour long lecture "The Character of Physical Law - Part 6 Probability and Uncertainty", he begins by saying that the more that we observe Nature, the less reasonable our explanations of Nature become. "Intuitively far from obvious" is one phrase he uses. Within the first ten minutes of the lecture he says things like:

We see things that are far from what we would guess. We see things that are very far from what we could have imagined and so our imagination is stretched to the utmost … just to comprehend the things that are there. [Nature behaves] in a way like nothing you have ever seen before. … But how can it be like that? Which really is a reflection of an uncontrolled but I say utterly vain desire to see it in terms of some analogy with something familiar… I think I can safely say that nobody understands Quantum Mechanics… Nobody knows how it can be like that.

Neither Flew nor Warren acknowledged the problem of intuition getting in the way of apprehending truth, nor possible approaches for dealing with it. We'll see how this problem affects Flew's Euthyphro argument.

About the law of the excluded middle: in general surely it can only be applied to terms and contrasts which are adequately sharp.

This is quite true. Logic, and computation, are based on objects that are distinguishable. This means that if two things can't be distinguished, then we can't accurately describe them. This means that God is beyond reason and logic, because He is not made of distinguishable parts, yet we talk about Him as if He is. At the heart of the Christian concept of God is what is to us a paradox: what God says is the same as what God is (because both are immaterial and unchanging), yet what God says is somehow different from what God is. Flew doesn't mention if this difficulty - that God is beyond reason - is one of the things that enters into his affirmation that there is no God.

My first and very radical point is that we cannot take it as guaranteed that there always is an explanation, much less that there always is an explanation of any particular desired kind.

Bravo, except that this shouldn't be radical. We know that empirical knowledge is incomplete (we'll never experience the interior of a black hole, at least not in any way we can talk about it) and, ever since Gödel, we know that knowledge based on self-referential logic is incomplete.

You can not argue: from your insistence that there must be answers to such questions; to the conclusion that there is such a being.

This. A thousand times this. Explanations are "just so" stories of which there can be no end. "Just so" stories that actually describe reality are much harder to devise.

For in the nature of the case there must be in every system of thought, theist as well as atheist, both things explained and ultimate principles which explain but are not themselves explained.

Note that Warren says the same thing: "God is the explanation which needs no explanation." In the final analysis, both sides end up with what they start with! Flew starts with "no god" and ends with "no god"; Warren starts with "god" and ends up with "god". Everything else in between are flawed arguments. I hope that once you see this happen, time and time again, that you see that what passes for a lot of "apologetics" are vain attempts to prove what has been assumed as true!

How often and when, when you make a claim to know something or other, do you undertake or expect to be construed as undertaking to provide a supporting demonstration of the kind which Dr. Warren so vigorously and so often challenges me to provide? Certainly when we claim to know anything, we do lay ourselves open to the challenge to provide some sort of sufficient reason to warrant that claim. But that sufficient reason can be of many kinds. And, although it may sometimes include some deductive syllogistic moves, the only case I can think of offhand in which a syllogism is the be-all and end-all of the whole business is that of a proposition in pure mathematics. Clearly that is not the appropriate model in the present case.

Again, Flew is right. The problem is that he doesn't say what the appropriate model is. He doesn't provide the testability criteria that he demands must be present (covered in the the next post).

The other way, which is the interesting one which I want to consider, is to urge that whereas we who have not enjoyed the revelatory experiences vouchsafed to the believer cannot reasonably be required to accept his claims, this believer himself is in a sure position to know.

Flew is basically saying that the "deaf" don't need to trust the "hearing". Here, Flew says "I haven't heard". Later, he will say, "I don't see." While he admits these things, he then needs to show that the theist is hallucinating and examine whether or not his presumption of atheism is the cause of his not hearing or seeing. As anyone who does puzzles knows, changing how you look at the puzzle can enable you to see things previously missed.

Flew gets positive marks for trying to lay a foundation of what it means to know; but negative marks for the incompleteness of his presentation. Having reviewed these points, the next post will examine Flew's three arguments.

Warren-Flew Debate, Part 1

Somewhere, in a place that I can no longer find1, I remember reading that Antony Flew was the "most important atheist you've never heard of." On the other hand, Flew may have abandoned atheism in favor of deism in 2004, six years before his death. One side says the switch may have been the result of senility - a charge which Flew denied2. Still, up until that point, he had an impressive pedigree. And in 1976, he debated Thomas Warren over a period of four nights in Denton, Texas where he argued for the affirmative position that there is no God. The debate is available on Youtube and in print.

My primary goal will be to examine Flew's arguments. My secondary goal will be to dissect Warren's responses to Flew. I have to admit that my sympathies -- but not my worldview -- are with Flew in the debate. My impression is that, of the two debaters, he is the more careful craftsman. He is trying to paint a picture with careful brush strokes while Warren is firing a paint gun. Flew is wielding a scalpel, while Warren is using a chain saw. Both have their uses, even though Flew removes the wrong organ and Warren cuts down the wrong tree.

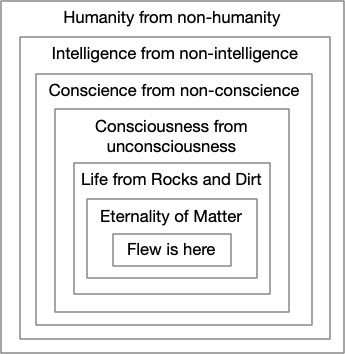

Because my sympathy is with Flew I will deal with his arguments last. First, I want to show where Warren's responses to Flew fall flat. First, Warren makes the claim that Flew has to hurdle seven walls; escape seven cages, to "know" that God does not exist. Warren presents his chart number 9 (manually recreated with minor edits):

And this leads to a fundamental problem. Neither side addresses what it means "to know". There is no mutual groundwork on the nature and limits of reason, empiricism, or self-evident knowledge. Warren has a way that he escapes the mutual prison cells, but I suspect he wouldn't permit Flew to use the same kind of tools. Warren says:

...the only way he can arrive at atheism is to come through all of these walls.

This simply isn't true. We know that knowledge obtained by empiricism is incomplete, if only because we can't experience everything. Thanks to Kurt Gödel, we know that knowledge obtained by reason, if it is consistent, is incomplete3. Both Warren and Flew need to address what it means to know in the face of uncertainty.

There are some things that we just can't know. And some of the things we claim to know by reason are built upon statements that are taken to be true for no other reason than they are assumed to be true. These axioms, these presuppositions, these self-evident truths may, or may not, conform to external reality (whatever that turns out to be4.) So while something might be logically true, it may not correspond to a correct description of Nature (cf. the "Stoddard" portion of the Spock-Stoddard Test).