Dialog with an Atheist #3

I prefer the academic definition of atheist: Belief that there are no gods.

I do not identify as an atheist.

I am a militant agnostic. I don't know, and you don't either.

@theosib2 and I have had numerous discussions about computer science and religion. In particular, we have gone back and forth about how we can test for 3rd party consciousness. It is absolutely impossible to objectively determine if something is conscious. The Inner Mind shows the physical reason why this is true. However, @theosib2 maintains this is not the case, even though I have pressed him to state what a function with this behavior is doing:

Objectively, it's a lookup table. Objectively, it has no meaning and no purpose. It's just a swirl of meaningless objects. Subjectively, it does have meaning and purpose, but we can't decide what it is. It could be a NAND gate or a NOR gate. Arrange these gates into a computer program and we might be able to determine what it is doing by its overall behavior. But we have to be able to map its behavior into behavior that we recognize within ourselves.

ξξ→ζ ξζ→ξ ζξ→ξ ζζ→ξ

With this as background, I responded to @theosib2:

“I’m conscious!”

“I don’t think so. You’re not carbon based.”

“I passed your Turing test, multiple times, when you couldn’t asses my form. I’m conscious, dammit.”

“I don’t know that you are. And you don’t, either.”

@theosib2 responded identically to "Victorian dad":

If only we could have a rigorous definition of consciousness. Then your comparison might be valid.

The endgame then played out as before:

Are you conscious?

Sometimes I wonder (with link to They Might Be Giants "Am I Awake?")

But only sometimes, right?

The atheist either has a problem with either knowing things that are subjectively known, or admitting the validity of subjective knowledge. Because if subjective knowledge is validly known, then demands for objective evidence for God are groundless. Because we have objective knowledge that mind is only known subjectively.

The Universe Inside

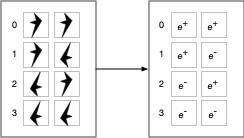

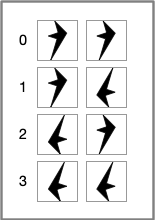

Let us replace distinguishable objects with objects that distinguish themselves:

Then the physical operation that determines if two elements are equal is:

As shown in the previous post, e+ (the positron and its behavior) and e- (the electron and its behavior) are the behaviors assigned to the labels "true" and "false". One could swap e+ and e-. The physical system would still exhibit consistent logical behavior. In any case, this physical operation answers the question "are we the same?", "Is this me?", because these fundamental particles are self-identifying.

From this we see that logical behavior - the selection of one item from a set of two - is fully determined behavior.

In contrast to logic, nature features fully undetermined behavior where a selection is made from a group at random. The double-slit experiment shows the random behavior of light as it travels through a barrier with two slits and lands somewhere on a detector.

In between these two options, there is partially determined, or goal directed behavior where selections are made from a set of choices that lead to a desired state. It is a mixture of determined and undetermined behavior. This is where the problem of teleology comes in. To us, moving toward a goal state indicates purpose. But what if the goal is chosen at random? Another complication is that, while random events are unpredictable, sequences of random events have predictable behavior. Over time, a sequence of random events with tend to its expected value. We are faced with having to decide if randomness indicates no purpose or hidden purpose, agency or no agency.

In this post, from 2012, I made a claim about a relationship between software and hardware. In the post, "On the Undecidability of Materialism vs. Idealism", I presented an argument using the Lambda Calculus to show how software and hardware are so entwined that you can't physically take them apart. This low-level view of nature reinforces these ideas. All logical operations are physical (all software is hardware). Not all physical operations are logical (not all hardware is software). Computing is behavior and the behavior of the elementary particles cannot be separated from the particles themselves. If we're going to choose between idealism and physicalism, it must be based on a coin flip2.

If computers are built of logic "circuits" then computer behavior ought to be fully determined. But when we add peripherals to the system and inject random behavior (either in the program itself, or from external sources), we get non-logical behavior in addition to logic. If a computer is a microcosm of the brain, the brain is a microcosm of the universe.

[1] Quarks have fractional charge, but quarks aren't found outside the atomic nucleus. The strong nuclear force keeps them together. Electrons and positrons are elementary particles.

[2] Dualism might be the only remaining choice, but I think that dualism can't be right. That's a post for another day.

Electric Charge, Truth, and Self-Awareness

What is truth?

— Pilate, John 18:38, NRSV

To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of

what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true.

— Aristotle

"The truth points to itself."

"What?"

"The truth points to itself."

"I do not understand."

"You will."

— Kosh and Delenn in Babylon 5:"In the Beginning"

The one quote that I want, but can no longer find, is to the effect that philosophers don't really know what truth is. Introductions to the philosophy of truth (e.g. here) make for fascinating reading. I claim that the philosophers can't reach agreement because they aren't trying to build a self-aware creature. Were they to attempt it, they might reason something like the following.

Aristotle's definition of truth is clumsy. It simplifies to:

If true then [say] true is true.

In hindsight, this isn't a totally terrible definition. It combines the behavior (say "true") with the behavior ("truth leads to truth"). But it's still circular. "True ... is true" doesn't tell us what truth is, so it's useless for building something.

Still, this formulation anticipated a definition of truth in computer programming languages by some 1,700 years:

if true then truth-action else false-action

"True" is a special symbol that is given the special meaning of truth. In Lisp, t is true and nil is false. In FORTRAN, .true. is true and .false. is false. Python uses True and False. And so on. But this still doesn't tell you what truth is other than it is a special symbol that can be used for making selections.

Looking at how "true" is defined in the Lambda Calculus provides a critical clue. Considering the Lambda Calculus is important, because it describes all computation in terms of behaviors (denoted by the special symbols λ, ., (, ), and blank) and meaningless symbols. There is no special symbol for "true".

def true = λx.λy.x

What this means is that "true" is a function of two objects, x and y and it returns the first object x. Truth is a behavior that can be used as a property. That is, this behavior can be attached to other symbols. It is the behavior that selects true things and rejects false things. False has symmetric behavior. It selects false things and rejects true things. So we've advanced from a special symbol to a behavior. But we aren't yet done.

The simplest if-then statement is:

if true then true else false

Truth is the behavior that selects itself. So we've derived the basis for the quote from Babylon 5, above. But we need to take one more step. Fundamental to the Lambda Calculus is the ability to distinguish between symbols. It is a behavior that is assumed by the Lambda calculus, one that doesn't have a special symbol like λ, ., (, ), and space to denote the behavior of distinguishing between symbols.

So consider a Lambda Calculus with two symbols:

And so, we find that truth is the ability to recognize self and select similar self-recognizing things.

And so, we find that electric charge gives us the laws of thought and truth, all in one force.

Electric Charge and the Laws of Thought

| Thought | Charge | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identity | Like charges repel, opposite charges attract |

| 2 | Non-contradiction | Positive charge is not negative charge |

| 3 | Excluded Middle | Charge is either positive or negative |

A Physicist's Questions

... most of the things that we consider to be intrinsic and instinctive human values are actually nothing of the sort; they are primarily and fundamentally the product of Christianity and would not exist without the last 2000 years of Christian dominance on our culture.

Today, in Creation Myths, by Marie-Louise Von Franz, I read:

Always at bottom there is a divine revelation, a divine act, and man has only had the bright idea of copying it. That is how the crafts all came into existence and is why they all have a mystical background. In primitive civilizations one is still aware of it, and this accounts for the fact that generally they are better craftsmen than we who have lost this awareness.

This suggests the more general case of a connection with the divine producing better results.

And this triggered the memory of an article by Dr. Lubos Motl written in 2015, "Can Christians be better at quantum mechanics than atheists"? Lubos makes some interesting statements. First, he answers his question generally affirmatively: "Apparently, yes." On the other hand, Lubos is an atheist and is an expert on quantum mechanics. Still, he notes:

In this sense, atheism is just another unscientific religion, at least in the long run.

"In this sense" being atheistic eisegesis, where the atheist attempts to impose their own prejudices onto Nature, instead of the other way around. Note that the Christian has this problem in double measure: not only must Christians avoid molding Nature into their own image, they must avoid molding God into their own image. They must be conformed to the Word, not conform the Word to themselves. Idolatry is a sin in both science and theology.

Nevertheless, in his post, Lubos asks some questions about Christianity that I'm going to attempt to answer. First, he asks:

A church surely wants the individual sheep to be passive observers, doesn't it?

Of course not. The church is a group of people who have been given a mission: to love one another and to make disciples throughout the entire world. We are to be active participants in the kingdom life. We don't "create our own world", but we don't do this in quantum mechanics, either. In both cases, the world reveals itself to us. After all, Wigner will get the same result as his friend.

But underneath Lubos' question is the idea of control: control by the church upon individuals and Lubos don't like outside control. He becomes rightfully incensed about suggestions, for example, that some questions should be off-limits to scientific inquiry. Yet consider one of the over-arching themes of the Bible, namely, order from chaos, harmony from static. This theme begins in Genesis and continues through Revelation. Static is maximally free. It cannot be compressed, there are no redundancies. Harmony requires a giving up of freedom. Totalitarians, whether secular or misguided Christians, will try to impose this order from without. Christianity says that this order must come from within, by the indwelling Spirit of God, received through the Lord Jesus Christ. It cannot be imposed by force of arms, but only through the reception of the Gospel. Each believer must find their own place(s) in the heavenly music.

But don't all religions actually want the only objective truth about the state of Nature to exist?

What we may want, and what actually is, are two different things. Still, Christianity says that we live by faith. This means we are uncertain as to what may come our way, even though we are certain as to God's faithfulness. As St. Paul wrote to the Corinthians, "for we see as though a glass, darkly."

Classical physics was doing great with omniscient God while quantum mechanics with its observer-dependence (and therefore "relativism" of a sort) seems to be more heretical, doesn't it?

Christianity is, in a sense, observer dependent, too. It claims that there are those who do not experience God and those who can. There are blind who do not see and deaf who do not hear. Furthermore, it claims that those who do not experience God cannot, unless God first works in them to restore their "spiritual" senses. But Lubos' question about omniscience contains a fact not in evidence, namely, that what we cannot foreknow (the outcome of a measurement before the measurement), God cannot also foreknow. There are no "hidden variables" in the natural world, but Scripture claims that there is hidden knowledge known only to God (eg. Dt. 29:29, et. al.) So on this point, the Christian and Dr. Motl will just have to disagree.

Science is ultimately independent of the religions – but it is independent of other philosophies such as the philosophies defended by the atheist activists, too.

Maybe. Science sees one part of the elephant, philosophy another. Until we have one theory of everything, I think this should remain an open question. I think Escher's Drawing Hands applies more to the relationship between science and philosophy than we might want to admit.

Dr. Larycia Hawkins and Wheaton College

Wheaton College has initiated termination proceedings against tenured professor Dr. Larycia Hawkins who has been a faculty member since 2007 and who received tenure in 2013. Wheaton is taking this action because of her statement that Christians and Muslims worship the same God. Apparently, this idea is counter to the Wheaton statement of faith. I note, for the record, that there is no explicit sentence in their statement of faith regarding which groups worship which God. Furthermore, in a FAQ published by Wheaton, question 7 asks "Is it true that Christians and Muslims worship the same God?" Wheaton lists doctrines which are distinctive to Christianity but are denied by Islam. But, note carefully, that Wheaton doesn't specifically answer the question with a simple "yes" or "no." For if they did, a bright undergraduate would then ask, "given this criteria, do Christians and Jews worship the same God?" I suspect Wheaton doesn't want that question to be asked.

But I digress. On December 17, 2015, Dr. Hawkins wrote to Wheaton in which she explained the reasons for her position as well as her personal statement of faith.

Opinion is of course, split, concerning the question of whether or not Muslims and Christians worship the same God. Dr. Edward Feser addressed the issue in the affirmative here. Vox Day, and many of his readers, answered in the negative, here. Last night at dinner, my wife initially said, "no"; this morning at breakfast, my reform seminary graduate friend Steve immediately said "yes."

I think Wheaton College is about to fall into a pit that they just don't yet see.

Let us consider two cases, one from literature and one from science. For literature, consider the two authors C. S. Lewis, who wrote the Narnia Chronicles, and Gene Roddenberry, who wrote Star Trek. Now suppose that there are two groups of people. One group asserts that humans owe their existence to having entered our world through a gate from Narnia. This is, of course, backwards from the way Lewis told the story in "The Magicians Nephew" — but bear with me. The other group asserts that humans originally came from the planet Vulcan. And again, in the original lore, it was the Romulans who were the offshoots of the Vulcans — just let me run with this. The only thing these two groups have in common is the idea that we came from somewhere else. Everything else is completely different and they are completely different because they are solely products of human imagination. Fans may argue the differences between Narnia and Star Trek, or Battlestar Galactica and Babylon 5. No one takes them seriously (except themselves) because we know it's "just fiction." It doesn't make sense to argue about which imaginary world is right.

Now consider the realm of science which attempts to discern how Nature works. We believe that this Nature exists independently of us. It is not a product of our imagination. At one time, science advanced the theory of the aether which was thought to be necessary for the propagation of light. But the Michelson-Morley experiments showed that this theory was wrong. Improvements to experiments to test Bell's inequality have shown that local realism isn't a viable theory of quantum mechanics. No discussion of misguided and incorrect scientific theories would be complete without mention of the famous phrase, attributed to Wolfgang Pauli, "That is not only not right, it is not even wrong." And let us not forget to mention String Theory, where some scientists say that not only is it not good science, it isn't science at all; while other scientists claim that it's really the only theory which can unite relativity and quantum mechanics. (As always, Lubos Motl is entertaining and instructive to read when it comes to String Theory).

In this case, we do not say, "you aren't studying the same nature we are." We say, "your understanding of nature is flawed."

If Wheaton continues down this path with Dr. Hawkins, whether they know it or not, they will be giving aid and comfort to those who claim that God is purely imaginary. And if they do that, then they are the ones who have betrayed their statement of faith.

Man Is The Animal...

Robots are deterministic finite state machines.

Dogs are non-deterministic finite state machines.

Humans are also non-deterministic finite state machines that have greater complexity than dogs (our ability to extend our memory through writing makes us, effectively, Turing machines, which are finite state machines that have infinite memory).

I will condense this to:

Man is the animal that uses external storage.

As of this posting, Google finds no matches for this sentence, nor does it match if "that" is replaced with "who". So I lay claim to originality of phrase.

Other examples of "man is the animal" below the fold.

Read More...

Dialog With An Atheist #2

wrf3, I've been reading your comments with some interest. You represent the kind of person who intrigues me.

Thank you?

Since I never know what spark can be ignited that will eventually start a fire of knowledge and understanding free of brainwashing, here goes.

I just love it how you automatically poison the well by using emotive terms like "brainwashing." We poor dumb biased Christians have been brainwashed, while you objective rational clear-thinking atheists have broken free. Just pathetic.

Does is bother you that you come across as having the whole truth and nothing but the truth--that you have all the answers? It should.

It doesn't, for the simple reason that "how I come across" is based more on your incomplete perception of me, rather than how I actually am. We all know that, in these politically correct times, offense can be taken where none was either intended, or given. In the same way, I suspect you're reading more into my responses than what I've actually written.

For the more a person knows the less s/he claims to know. Tell us what you don't know pertaining to religious truth, if you want to prove me wrong.

That would fill a book. Shall I write another book about what I don't know about mathematics, even though I have a degree in math? How about a book about what I don't know about science, even though my math degree is from an engineering school, so I've had to take physics, chemistry, biology, thermodynamics, circuits and devices, astronomy, materials science, …?

I'll be curious to learn if you admit ignorance about several important basic details of your particular religious worldview, while at the same time claiming certainty about the whole worldview itself. That would be odd wouldn't you think, if you admit ignorant of the foundational details but certain of the whole?

First, you tell me what the "foundational details" you think I'm ignorant of. Because we may disagree on what is foundational and what is derived.

Second, by your criteria, I should throw out the American Constitution and Quantum Mechanics. I should throw out the American Constitution because there is no universal agreement on what the 2nd amendment means. Even the Supreme Court was divided, 5-4, on whether or not the 2nd Amendment guarantees the right of individuals to own firearms.

And we should throw out Quantum Mechanics, because while most everyone agrees on Schrödinger's equation, there is widespread disagreement on how to interpret it. Copenhagen, Many-worlds, De Broglie-Bohm, ... You might enjoy the articles Lubos Motl posts about idiot scientists who say idiotic things about science. This one is a recent one about a paper published in Nature. And this one about proponents of the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics…

Let me link to a few items for your reflection on this question. ... Christians debate many doctrinal and foundational specifics, as seen in these books. Are you claiming to know the answers for every issue?

Of course not. Ask me which eschatological view I hold. On Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays I prefer amillennialism. On Thursdays I like postmillennialism. On Fridays I reflect on partial preterism. On Saturdays, I consider historic dispensationalism.

So there are ambiguities. So what? That's true of anything, whether it is interpretation of Christian doctrine, interpretation of the American Constitution, or interpretation of nature.

It's how our neural nets work.

Shall we declare science wrong because scientists can't agree on how to interpret nature via quantum mechanics?

In one of these above books, on apologetics, several authors argue against presuppositionalism. I suppose you are certain they are wrong too, correct?

If by "presuppositionalism" you mean "Christian presuppositionalism" then, yes, they are wrong.

Go back and re-read what I wrote. As a mathematician, I will say that we cannot escape our axioms. What we believe controls how we evaluate evidence. Then I said that I think that atheism is a consistent, complete worldview. I also said that Christianity is a consistent, complete worldview.

That doesn't mean that there aren't inconsistent Christians, or inconsistent Atheists. im-skeptical is an inconsistent atheist. He could be a consistent atheist, but whether or not he has that eureka moment only time will tell.

See a trend here? You are correct. Every other Christian is wrong. Seriously?

Only in your imagination.

The historical trend is also telling, ...

Are you saying that truth is determined by numbers? Really? And 100, or 200, or 1,000 years from now, when the trend has changed, will your great-great-great grandchildren try to use the same argument?

There are several former believers who no longer believe. ... Have you read these works?

Some of them. On the other hand, there are former atheists who now believe. Me, for one. C. S. Lewis, for another.

So what? If I have to weigh intellect against intellect, I'd certainly put C. S. Lewis ahead of John Loftus, or Bart Ehrman.

But what you don't understand is that I'm not playing that game. Atheism vs. Christianity isn't about evidence. It never has been. It's about how brains process evidence.

Let's say that it's possible you are wrong.

I'm a software engineer. I'm also married. I'm wrong a thousand times a day.

Wouldn't you want to know? No, seriously, wouldn't you want to know, yes or no?

Of course I would.

How about you?

You have Christians debunking themselves, where the trend is from conservatism to atheism, with several former intellectual believers several rejecting your faith and writing about it.

Truth has never, ever been about numbers. That you even try this argument means that you don't know how epistemology works. You're exhibiting the "r" side of r/K selection traits (i.e. where group consensus is more important than anything else).

And that you commit the fallacy of "selective citing" only shows how bankrupt your argument is. Note that this doesn't prove that Christianity is right and atheism is wrong. It just proves that you are an ignorant atheist, as opposed to an intelligent atheist.

Wouldn't you want to know why this is the case? Satan is too easily an answer. You would not accept that as an answer if someone said YOUR theology was of Satan, would you?

Why don't you let me provide my own answers? Otherwise, you can just have a conversation with yourself and whatever straw-men you want to talk to.

My claim is that doubt should be the position of everyone until such time as the evidence shows otherwise.

A self-defeating philosophy if ever there was one because, if you really believed it, you would doubt it and enter into a vicious circle.

And, for the last time, you're trying to argue evidence with someone who says that it isn't about the evidence. After all, if both Christianity and atheism are complete consistent systems, there isn't any evidence that can possibly exist to settle the argument one way or another.

The Regulative Principle

Read More...

The Physical Nature of Thought

Two monks were arguing about a flag. One said, "The flag is moving." The other said, "The wind is moving." The sixth patriarch, Zeno, happened to be passing by. He told them, "Not the wind, not the flag; mind is moving."

-- "Gödel, Escher, Bach", Douglas Hofstadter, pg. 30

Is thought material or immaterial? By "material" I mean an observable part of the universe such as matter, energy, space, charge, motion, time, etc... By "immaterial" would be meant something other than these things.

Russell wrote:

The problem with which we are now concerned is a very old one, since it was brought into philosophy by Plato. Plato's 'theory of ideas' is an attempt to solve this very problem, and in my opinion it is one of the most successful attempts hitherto made. … Thus Plato is led to a supra-sensible world, more real than the common world of sense, the unchangeable world of ideas, which alone gives to the world of sense whatever pale reflection of reality may belong to it. The truly real world, for Plato, is the world of ideas; for whatever we may attempt to say about things in the world of sense, we can only succeed in saying that they participate in such and such ideas, which, therefore, constitute all their character. Hence it is easy to pass on into a mysticism. We may hope, in a mystic illumination, to see the ideas as we see objects of sense; and we may imagine that the ideas exist in heaven. These mystical developments are very natural, but the basis of the theory is in logic, and it is as based in logic that we have to consider it. [It] is neither in space nor in time, neither material nor mental; yet it is something. [Chapter 9]

I claim that Russell and Plato are wrong. Not necessarily that ideas exist independently from the material. They might.1 Rather, I claim that if ideas do exist apart from the physical universe, then we can't prove that this is the case. The following is a bare minimum outline of why.

Logic

Logic deals with the combination of separate objects. Consider the case of boolean logic. There are sixteen way to combine apples and oranges, such that two input objects result in one output object. These sixteen possible combinations are enumerated here. The table uses 1's and 0's instead of apples and oranges, but that doesn't matter. It could just as well be bees and bears. For now, the form of the matter doesn't matter. What's important is the outputs associated with the inputs2.Composition

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that we have 16 devices that combine things according to each of the 16 possible ways to combine two things into one. We can compose a sequence of those devices where the output of one device becomes the input to another device. We first observe that we don't really need 16 different devices. If we can somehow change an "orange" into an "apple" (or 1 into 0, or a bee into a bear) and vice versa, then we only need 8 devices. Half of them are the same as the other half, with the additional step of "flipping" the output. With a bit more work, we can show that two of the sixteen devices when chained can produce the same output as any of the sixteen devices. These two devices, known as "NOT OR" (or NOR) and "NOT AND" (or NAND) are called "universal" logic devices because of this property. So if we have one device, say a NAND gate, we can do all of the operations associated with Boolean logic.3Calculation

NAND devices (henceforth called gates) are a basis for modern computers. The composition of NAND gates can perform addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and so on. As an example, the previously referenced page concluded by using NAND gates to build a circuit that added binary numbers. This circuit was further simplified here and then here.Memory

We further observe that by connecting two NAND gates a certain way that we can implement memory.Computation

Memory and calculation, all of which are implemented by arrangements of NAND gates, are sufficient to compute anything which can be computed (cf. Turing machines and the Church-Turing thesis).Meaning

Electrons flowing through NAND gates don't mean anything. It's just the combination and recombination of high and low voltages. How can it mean anything? Meaning arises out of the way the circuits are wired together. Consider a simple circuit that takes two inputs, A and/or B. If both inputs are A it outputs A, if both inputs are B then it outputs A, and if one input is A and the other is B, it outputs B. By making the arbitrary choice that "A" represents "yes" or "true" or "equal", more complex circuits can be built that determine the equivalence of two things. This is the simplified version of Hofstadter's claim:

When a system of "meaningless" symbols has patterns in it that accurately track, or mirror, various phenomena in the world, then that tracking or mirroring imbues the symbols with some degree of meaning -- indeed, such tracking or mirroring is no less and no more than what meaning is.

-- Gödel, Escher, Bach; pg P-3

Neurons and NAND gates

The brain is a collection of neurons and axons through which electrons flow. A computer is a collection of NAND gates and wires through which electrons flow. The differences are the number of neurons compared to the number of NAND gates, the number and arrangement of wires, and the underlying substrate. One is based on carbon, the other on silicon. But the substrate doesn't matter.That neurons and NAND gates are functionally equivalent isn't hard to demonstrate. Neurons can be arranged so that they perform the same logical operation as a NAND gate. A neuron acts by summing weighted inputs, comparing to a threshold, and "firing" if the weighted sum is greater than the threshold. It's a calculation that can be done by a circuit of NAND gates.

Logic, Matter, and Waves

It's possible to create logic gates using particles. See, for example, the Billiard-ball computer, or fluid-based gates where particles (whether billiard balls or streams of water) bounce off each other such that the way they bounce can implement a universal gate.It's also possible to create logic gates using waves. See, for example, here [PDF] and here [paid access] for gates using acoustics and optics.

I suspect, but need to research further, that waves are the proper way to model logic, since it seems more natural to me that the combination of bees and bears is a subset of wave interference rather than particle deflection.

Self-Reference

4 So why are Russell and Plato wrong? It is because it is the logic gates in our brains that recognize logic, i.e. the way physical things combine. Just as a sequence of NAND gates can output "A" if the inputs are both A or both B; a sequence of NAND gates can recognize itself. Change a wire and the ability to recognize the self goes away. That's why dogs don't discuss Plato. Their brains aren't wired for it. Change the wiring in our brains and we wouldn't, either. Hence, while we can separate ideas from matter in our heads, it is only because of a particular arrangement of matter in our heads. There's no way for us to break this "vicious" circle.

4 So why are Russell and Plato wrong? It is because it is the logic gates in our brains that recognize logic, i.e. the way physical things combine. Just as a sequence of NAND gates can output "A" if the inputs are both A or both B; a sequence of NAND gates can recognize itself. Change a wire and the ability to recognize the self goes away. That's why dogs don't discuss Plato. Their brains aren't wired for it. Change the wiring in our brains and we wouldn't, either. Hence, while we can separate ideas from matter in our heads, it is only because of a particular arrangement of matter in our heads. There's no way for us to break this "vicious" circle.Footnotes

[1] "In the beginning was the Word..." As a Christian, I take it on faith that the immaterial, transcendent, uncreated God created the physical universe.[2] Note that the "laws of logic" follow from the world of oranges and apples, bees and bears, 1s and 0s. Something is either an orange or an apple, a bee or a bear. Thus the "law" of contradiction. An apple is an apple, a zero is a zero. Thus the "law" of identity. Since there are only two things in the system, the law of the excluded middle follows.

[3] This previous post shows how NAND gates can be composed to calculate all sixteen possible ways to combine two things.

[4] "Drawing Hands", M. C. Escher

Quantum Mechanics and Reformation Theology

Several weeks ago, the teacher stated (paraphrasing) that "we believe 2+2=4 because of the axioms of mathematics." However, in "Quantum Computing Since Democritus", on page 10, Aaronson writes:

How can we state axioms that will put the integers on a more secure foundation, when the very symbols and so on that we're using to write down the axioms presuppose that we already know what the integers are?

Well, precisely because of this point, I don't think that axioms and formal logic can be used to place arithmetic on a more secure foundation. If you don't already agree that 1+1=2, then a lifetime of studying mathematical logic won't make it any clearer!

Today, in passing, it was said that responsibility necessitates the free will of man. Nothing could be further from the truth. I continued my reading of Aaronson during lunch today and came across this gem on pages 290-291:

Before we start, there are two common misconceptions that we have to get out of the way. The first one is committed by the free will camp, and the second by the anti-free-will camp.

The misconception committed by the free will camp is the one I alluded to before: if there's no free will, then none of us are responsible for our actions, and hence (for example) the legal system would collapse….

Actually, I've since found a couplet by Ambrose Bierce that makes the point very eloquently:

"There's no free will," says the philosopher;

"To hang is most unjust."

"There is no free will," assent the officers.

"We hang because we must."

Looking ahead to the end of the chapter, Aaronson brings Conway's "Free-Will Theorem" into play. What he doesn't apparently discuss (I've just scanned here and there), is that this randomness is not under our control.

Gems from John R. Pierce

"Mathematically, white Gaussian noise, which contains all frequencies equally, is the epitome of the various and unexpected. It is the least predictable, the most original of sounds. To a human being, however, all white Gaussian noise sounds alike. It's subtleties are hidden from him, and he says that it is dull and monotonous. If a human being finds monotonous that which is mathematically most various and unpredictable, what does he find fresh and interesting? To be able to call a thing new, he must be able to distinguish it from that which is old. To be distinguishable, sounds must be to a degree familiar. … We can be surprised repeatedly only by contrast with that which is familiar, not by chaos." [pg. 251, 267]

Christianity and Computer Science

But what to study? My standard response these days is either theology or computer science. Then I add that I'm not sure that I really see a difference between the two. While driving in to work this morning, my subconscious found that my flippancy isn't so far off the mark. If thought is matter in motion in certain patterns (which it is), then writing software is the act of putting thought in physical form. A moment's reflection shows that this must be so: the computer is all hardware. The software is just ones and zeros but, again, this is just a collection of physical states arranged in specific ways. If the criticism is that "computers don't think!", the answer is that this is because computers don't have the huge number of connections that are in the human brain. But in time they will.

Putting thought in physical form is what God did with His Son. "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. … And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us." Jesus is God's thoughts in physical form.

So Christianity and computer science are both incarnational.

Modeling the Brain

The "autonomous" section is concerned with the functions of the brain that operate apart from conscious awareness or control. It will receive no more mention.

The "introspection" division monitors the goal processing portion. It is able to monitor and describe what the goal processing section is doing. The ability to introspect the goal processing unit is what gives us our "knowledge of good and evil." See What Really Happened In Eden, which builds on The Mechanism of Morality. I find it interesting that recent studies in neuroscience show:

But here is where things get interesting. The subjects were not necessarily consciously aware of their decision until they were about to move, but the cortex showing they were planning to move became activated a full 7 seconds prior to the movement. This supports prior research that suggests there is an unconscious phase of decision-making. In fact many decisions may be made subconsciously and then presented to the conscious bits of our brains. To us it seems as if we made the decision, but the decision was really made for us subconsciously.

The goal processing division is divided into two opposing parts. In order to survive, our biology demands that we reproduce, and reproduction requires food and shelter, among other things. We generally make choices that allow our biology to function. So part of our brain is concerned with selecting and achieving goals. But the other part of our brain is based on McCarthy's insight that one of the requirements for a human-level artificial intelligence is that "All aspects of behavior except the most routine should be improvable. In particular, the improving mechanism should be improvable." I suspect McCarthy was thinking along the lines of Getting Computers to Learn. However, I think it goes far beyond this and explains much about the human mind. In particular, introspection of the drive to improve leads to the idea that nothing is what it ought to be and gives rise to the is-ought problem. If one part of the goal processing unit is focused on achieving goals, this part is concerned with focused on creating new goals. As the arrows in the diagram show, if one unit focuses toward specific goals, the other unit focuses away from specific goals. Note that no two brains are the same -- individuals have different wiring. In some, the goal fixation process will be stronger; in other, the goal creation process will be stronger. One leads to the dreamer, the other leads to the drudge. Our minds are in dynamic tension.

Note that the goal formation portion of our brains, the unit that wants to "jump outside the system" is a necessary component of our intelligence.

The No Free Will Theorem

Earlier this week, over at Vox Popoli, Vox took issue with a particular scientific study that concluded on the basis of experimental data that free will does not exist. While I think I agree that this study does not show what it claims to show, I nevertheless took the approach the free will doesn't exist. The outline of a proof goes like this.

Either thought follows the laws of physics, or it does not. X or ~X. I hold the law of non-contradiction to be true. Now, someone might quibble about percentages: most of the time our thoughts follow the laws of physics, but sometimes they do not. But that misses the point.

Why would anyone suppose that our thoughts don't follow the laws of physics? Perhaps because of an idea that thought is "mystical" stuff; that there is a bit of "god stuff" in our heads that gives us the capabilities that we have. If this were so, since the Christian God transcends nature, our thoughts would transcend nature. It's how we would avoid non-existence upon physical death: the "soul" which is made of "god stuff" returns to God. Perhaps it's due to not knowing how thinking is accomplished in the brain. What I'm about to say certainly isn't taught in any Sunday school I've ever attended, or been discussed in any theological book I've ever read. While that may be because I don't get out enough, I suspect my experience isn't atypical. Another, more general reason, is because that's the way our brains perceive how they operate. It's the "default setting," as it were. Most people, regardless of upbringing, think they have free will. I think I can explain why it's that way, but that's for another post.

How does one prove that thoughts follow the laws of physics? The ultimate test would be to build a human level artificial intelligence. I can't do that. The technology isn't there. Yet. The best I can do is offer a proof of concept. I maintain that this is better than what the proponent of mystical thought can do. I know of no way to build something that doesn't obey the laws of physics. By definition, we can't do it. So any proof would have to come form some source from outside nature held to be authoritative. In my world, that's typically the Bible. There is no end of Bible scholars who hold that Scripture teaches that man has free will. It doesn't, but my intent here is to make may case, not refute their arguments. Although I acknowledge that it certainly wouldn't hurt to do so elsewhere.

What is thought? Thought is matter in motion in certain patterns. This is a key insight which must be grasped. The matter could be photons, it could be water; in our brain it is electrons. The pattern of the flow of electrons is controlled by the neurons in our brain, just like the pattern of the flow of electrons is controlled by NAND gates in a computer. While neurons and NAND gates are different in practice, they are not different in principle. NAND gates can simulate neurons (there are, after all, computer programs that do this) and neurons can simulate NAND gates (cf. here). Another way to view this is that every time a programmer writes computer software, they are embedding thought into matter. I've been programming professionally for almost 40 years and it wasn't until recently that I understood this obvious truth. But if this is so, why aren't there intelligent computers? As I understand it, there are some 100 billion neurons in the brain with some 5 trillion connections. Computers have not yet achieved that level of complexity. Can they? How many NAND gates will it take to achieve the equivalent functionality of 5 trillion neuron connections? I don't know. But the principle is sound, even if the engineering escapes us.

Humans are governed by the laws of quantum mechanics, just as computers are. Having just re-watched all four seasons of Battlestar Galactica on Netflix, it was fascinating to watch the denial of some humans that machines could be their equal, and the denial of some machines that they could be human. In the season 4 episode No Exit, the machine's complaint to his creator "why did you make me like this," is straight out of Romans 9. Art, great art, imitating life.

However one cares to define the concept of "free will," that definition must apply to computers as equally as it does to man. The same principles govern both. As long as it meets that criteria, I can live with silly notions of what "free" means. "You are free to wander around inside this fenced area, but you can't go outside" is usually how the definitions end up. I think limited freedom is an oxymoron, but people want to cling to their illusions.

There is so much more to cover. If our thoughts are the movement of electrons in certain patterns, then how is that motion influenced? What are the feedback loops in the brain? What is the effect of internal stimuli and external stimuli? Is one greater than the other? The Bible exhorts the Christian to place themselves where external stimuli promotes the faith. The dances of their electrons can influence the dance of our electrons. Can we make Christians (or Democrats, or Atheists, or…) through internal modification of brain structures through drugs or surgery? How does God change the path of electrons in those who believe versus those who don't? Would God save an intelligent machine? Could they be "born again"? Does God hide behind quantum indeterminacy? So many questions.

In April 2009, I wrote the post Ecclesiastes and the Sovereignty of God, which gave excepts from the book A Time to Be Born - A Time to Die, by Robert L. Short. Using the Bible, in particular the book of Ecclesiastes, Short reaches the same conclusion I do arguing from basic physics.

The universe controls us. We do not control the universe.

This brings me to the Gene Wolfe quote mentioned at the beginning of this post:

This is what mankind has always wanted. … That the environment should respond to human thought. That is the core of magic and the oldest dream of mankind…. when humankind has dreamed of magic, the wish behind the dream has been the omnipotence of thought.

[to be continued]

On the Inadequacy of Scientific Knowledge

If true, that rule is not a minor flaw in scientific reasoning. The law is completely nihilistic. It is a catastrophic logical disproof of the general validity of all scientific method!

If the purpose of scientific method is to select from a multitude of hypothesis, and if the number of hypothesis grows faster than the experimental method can handle, then it is clear that all hypothesis can never be tested. If all hypothesis cannot be tested, then the results of any experiment are inconclusive and the entire scientific method falls short of its goal of establishing proven knowledge.

About this Einstein had said, "Evolution has shown that at any given moment out of all conceivable constructions a single one has proved absolutely superior to all the rest," and let it go at that. But to Phaedrus3 that was an incredibly weak answer. The phrase "at any given moment" really shook him. Did Einstein really mean to state that truth was a function of time? To state that would annihilate the most basic presumption of all science!

But there it was, the whole of history of science, a clear story of continuously new and changing explanations of old facts. The time spans of permanence seemed completely random, he could see no order to them. Some scientific truths seemed to last for centuries, others for less than a year. Scientific truth was not a dogma, good for eternity, but a temporal quantitative entity that could be studied like anything else.

He studied scientific truths, then became upset even more by the apparent cause of their temporal condition. It looked as though the time spans of scientific truths are an inverse function of the intensity of scientific effort. Thus the scientific truths of the twentieth century seem to have a much shorter life-span than those of the last century because scientific activity is now much greater. If, in the next century, scientific activity increases tenfold, then the life expectancy of any scientific truth can be expected to drop to perhaps one-tenth as long as now. What shortens the lifespan of the existing truth is the volume of hypothesis offered to replace it; the more the hypothesis, the shorter the time span of the truth. And what seems to be causing the number of hypothesis to grow in recent decades seems to be nothing other than scientific method itself. The more you look, the more you see. Instead of selecting one truth from a multitude, you are increasing the multitude. What this means logically is that as you try to move toward unchanging truth through the application of scientific method, you actually do not move toward it at all. You move away from it. It is your application of scientific method that that is causing it to change!

What Phaedrus observed on a personal level was the phenomenon, profoundly characteristic of the history of science, which has been swept under the carpet for years. The predicted results of scientific enquiry and the actual results of scientific enquiry are diametrically opposed here, and no one seems to pay much attention to the fact. The purpose of scientific method is to select a single truth from among many hypothetical truths. That, more than anything else, is what science is all about. But historically science has done exactly the opposite. Through multiplication upon multiplication of facts, information, theories, and hypotheses, it is science itself that is leading mankind from single absolute truths to multiple, indeterminate, relative ones. The major producer of the social chaos, the indeterminacy of thought and values that rational knowledge is supposed to eliminate, is none other than science itself. And what Phaedrus saw in the isolation of his own laboratory work is now seen everywhere in the technological world today. Scientifically produced antiscience -- chaos.

There is a lot to consider and commend in this argument. Certainly, anyone who has uttered, "the more I know the less I know" understands that as knowledge increases the unknown also appears to increase. Every advance in knowledge pushes out the unexplored frontier. It is unclear how much there is to be known. Even if an argument to the boundedness of knowledge about the physical universe could be made based upon the number of particles therein, I suspect we will find limits to how far we can explore. We likely cannot know all that could be known. And this omits the field of mathematical knowledge, where Gödel showed the incompleteness of formal systems.

The idea that scientific knowledge is a function of time needs to be stressed. Now I happen to think4 that the recent Opera claim of superluminal neutrinos won't stand upon further investigation, but if it does it will require adjustments to relativity.

Finally, if it is true that science produces antiscience then the resulting chaos can't be repaired by more application of the scientific method, unless scientific knowledge is finite.

While I think that much of this argument has merit, I put it in the Bad Arguments category, not because I necessarily disagree with the conclusions, but because the premise that "the purpose of the scientific method is to select a single truth from many hypothetical truths" is wrong. The scientific method is not "when I repeatedly do this I get that result therefore this result can always be expected". That's observation and induction, no different from "the sun rose yesterday, the sun rose today, therefore the sun will rise tomorrow." We know there will come a time when the sun won't rise the next day. Induction is not a sure means to truth, even though we often have to rely on it.5 As Einstein said, "No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong."6

The power of the scientific method comes from the logical equation: (A → B) ∧ ¬B → ¬A. In English, "if A implies B, and B is not true, then A is not true." Experiments don't establish theories, they show if a theory is wrong. The scientific method doesn't establish truth, it establishes falsehood. Consider a piece of paper as an analogy to knowledge. Let the color gray represent what we don't know. Let white represent truth. Let black stand for falsehood. The paper starts out gray. We don't know if the paper is finite or infinite in extent. Science can turn gray areas black, to represent the things we know are not true. But it can't turn gray areas white.

And yet, the earth revolves around the sun and E=mc2. Even if superluminal neutrinos really do exist, atomic weapons still work by turning a little bit of matter into a lot of energy. How we go from gray to white is another topic for another day. But with the correction of Pirsig's premise, much of his argument still follows.

[1] In the Author's Note, Pirsig writes "[this book] should in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice. It's not very factual on motorcycles either."

[2] Pg. 559. I don't know why I bother with page numbers, as they vary from e-reader to e-reader.

[3] Phaedrus is the author in an earlier stage of his life.

[4] I'm no expert. Don't wager based on my opinion.

[5] See On Induction by Russell.

[6] This appears to be a paraphrase. See here.

Theism vs. Atheism Debate Update

It has been almost eight weeks since I last posted on the Theism vs. Atheism debate. The delay is partly due to the busyness of life interfering with blogging. But mainly, the delay is due to my wanting to finish the Yale course on game theory, since this is critical to developing the argument for a biological basis for morality. I also need to finish taking notes on Lewis' Mere Christianity, since one of Lewis' arguments for the existence of God is a nearly universal morality which, broadly speaking, equates to one of the variants of the Golden Rule. See here, for example, for the Golden Rule in ancient Egypt 2,000 years before Christ.

I'm also finding interesting articles which have to be worked into the biological theory of morality, such as ParaPundit's "Non-conformists Better At Working Toward Common Good", which I highly commend to your attention. Since this mentions the positive role of the nonconformist in society, with the recent passing of Steve Jobs, it is fitting to mention this except from the Newsweek article, "Exit the King" from the Sept. 5 issue:

After becoming rich and famous in his early 20s, he realized that he needed colleagues who weren't awed by his myth and could assert themselves forcefully against him – especially since he was at once strong-willed but under educated and inexperienced and still insecure about his judgment. He found that by delivering brutal putdowns of his co-workers he could test the strength of their conviction in their own ideas. If he said "this sucks" or "this is sh!t" and they fought back fiercely, he would trust their passion, especially since he often lacked the necessary technical acumen or aesthetic confidence. (Even though he instinctively grasped the importance of design from early on – he had wanted to enclose the Apple I in a case of beautiful blond koa wood – he remained uncertain about his taste for many years before he settled on the safety of austere minimalism). He found that many of the most brilliant engineers and creative types actually responded well to cruel criticism, since it reinforced their own secret belief that they weren't living up to their vaunted potential. Jobs's relentlessly high standards inspired their own maniacal work.

Continuing with the theme of the need for the non-conformists, Here's To The Crazy Ones, narrated by Steve Jobs:

[The video was removed by YouTube due to alleged copyright infringement]

Theism vs. Atheism, Part 2

Here, I want to address the problem of thought. Some Christians assert that human thought does not follow the laws of physics and that it cannot do so. Man is a body and a soul, or body, soul, and spirit, where at least one of soul or spirit is supernatural and is what makes us human. Atheists, of course, assert that thought is just matter in motion in certain patterns.

An in depth treatise on this won't fit in 2,000 words, so I will just sketch the outline of the materialist case. We know that the logical operations of and, or, and not are capable of expressing all statements of boolean logic. We also know that the nand (not and) and nor (not or) operators can do the same thing: (nand x x) = (not x), (nand (nand x y) (nand x y)) = (and x y), (nand (nand x x) (nand y y)) = (or x y). This means that we can string together any number of nand (or nor) gates together to implement boolean statements. In addition, nand gates can be used to implement memory, multiplexers, demultiplexers and in, general, the elements of a computer. A set of nand gates in one configuration results in an adder; a different set of nand gates results in something that can recognize whether or not a particular circuit is an adder or not. Both represent electrons flowing in a certain pattern.

We are used to thinking of software and hardware as two different things: but they both reduce to a particular arrangement of nand gates. Software is just electrons moving in a certain pattern.

Now, software is, at least, a subset of thought, so we have established that human thought, insofar as it is software, is "just" electrons in motion. And, certainly, our brains consist of axons which use chemical reactions to shuffle electrons around. Furthermore, we know that the brain can be damaged with a resultant change in the ability to think. Alcohol, for example, is one way to temporarily disrupt the flow of electrons from their usual patterns.

Is thought more than just complex software? Opinion on this is, of course, mixed. Ashwin Ram of Georgia Tech gives a concise readable look at some of the issues here. Hofstatder took 832 pages to explore the issue in his landmark Gödel, Escher, Bach. Obviously, the only way to show that our minds are complex software is to build a human-level artificial intelligence, and our ability to do this isn't quite there, yet. But this doesn't mean we can't explore how it would be done. To do this, I have to deal with (at least) two theistic objections: absolute truth and morality.

What is truth?

Christians sometimes argue that materialism does not give a sufficient basis for reason. For example, C. S. Lewis wrote, "One absolutely central inconsistency ruins [the popular scientific philosophy]. The whole picture professes to depend on inferences from observed facts. Unless inference is valid, the whole picture disappears... unless Reason is an absolute[,] all is in ruins. Yet those who ask me to believe this world picture also ask me to believe that Reason is simply the unforeseen and unintended by-product of mindless matter at one stage of its endless and aimless becoming. Here is flat contradiction. They ask me at the same moment to accept a conclusion and to discredit the only testimony on which that conclusion can be based."1 Similarly, J. B. S. Haldane wrote, “It seems to me immensely unlikely that mind is a mere by-product of matter. For if my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true. They may be sound chemically, but that does not make them sound logically. And hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms.”2

Earlier I wrote that I'm not aware of a catalog of basic beliefs. Let me start one by citing A. J. Hoover:3

Probably the most basic law of human thought is the principle of contradiction. Some call it the “Law of Contradiction,” others call it the “Law of Noncontradiction.” Both terms refer to the same thing. Whatever you call it, this principle is the basis of all rational thought and rational communication.

What is a contradiction? It is not so much a thing as it is an event. A contradiction occurs when two statements can’t possibly be true at the same time and in the same relationship. If I say, “It is raining here right now,” that contradicts the assertion, “It is not raining here right now.” Both of these statements cannot be true at the same time.

Logicians usually identify three laws that all seem to stem from the basic principle of contradiction:

The law of contradiction asserts that A can’t both be A and non-A at the same time and in the same relationship.

The law of identity asserts that A is A; that every event and every judgement is identical with itself.

The law of excluded middle asserts that everything must be A or non-A.

These three laws, taken together, make it possible for us to communicate rationally.

Now, there are multi-valued and fuzzy logics but, leaving those aside, we believe these three laws because we have to. We couldn't communicate without them. They work. Similarly, we hold Euclid's axioms to be true because they work, even though the universe may ultimately be shown to be non-Euclidean. Inference is valid for the same reason -- it usually works (cf. Russell's On Induction). Lewis' argument fails because "Reason" doesn't have to be absolute. It just has to be good enough to allow us to grow food, build bridges that stay up, land men on the moon, raise children, and argue with one another. Haldane's argument fails because, while there may not be "a reason to suppose my beliefs are true" there likewise isn't a reason to suppose they are false. We are constantly analyzing our body to knowledge to see if it is internally consistent and coherent with external reality (whatever that may end up being). We have to live with uncertainty.

An Algorithmic Basis for Morality

Morality is an area where theists think they have a strong argument. Certainly, Sam Harris' attempt to provide a science of morality in The Moral Landscape was a dismal failure. However, both sides are remiss in that neither side has produced a definition of morality that isn't circular (cf. a very, very early post of mine, "Good and Evil, Part I").

Recall fact D (our brains are goal-seeking engines with variable goals). We understand how to model goal seeking behavior as finding a path in a graph from some initial state to some goal state.3 A path that leads from an initial state to a goal state is good; a shorter path between the two points might be better (depending on other goals); the shortest path might be best (again, depending on any additional constraints). Likewise, paths leading away from a goal state are deemed bad. Fact A stated that we are partially self-aware. This self-awareness extends to our ability to partially introspect our goal seeking behavior and this is what gives us a knowledge of good and evil.

Note that Harris hypothesized that the brain would show differences when making a moral decision as opposed to other types of decisions. He didn't need to do his neuroimaging experiments to show that this was not the case; after all, a computer uses the same circuitry to compute an integral as it does to evaluate a game tree. They aren't fundamentally different kinds of operations.

Since morality is essentially a search operation through a state space, it is an algorithm that can be encoded in nand gates or axons, and, therefore, is electrons in motion in a certain pattern. This idea is bolstered by the experiments at MIT where the moral judgements of test subjects could be swayed by the application of a magnetic field to the scalp.4

McCarthy's third design requirement from fact D, "all aspects of behavior except the most routine must be improvable. In particular, the improving mechanism should be improvable" has some remarkable consequences. If everything can be improvable, then nothing is what it ought to be. This gives rise to Hume's is-ought distinction.5 It also gives a basis for the problem of theodicy: if everything can be improved, nothing is what it ought to be. In particular, god is not what he ought to be. This is why the problem of evil is not a valid argument against theism. It also explains the Christian notion of "sin" (Greek amartia - "to miss the mark") since we are not what we ought to be. It's interesting to note that some brains focus on the former, while some brains focus on the latter. Our brains are in dynamic tension between wanting to settle on a goal and wanting to change the goal and keep searching.6 It would be an interesting experiment to classify where atheists and theists fall in this range. Perhaps theists are those whose bias is to reach a goal, while atheists are those who have a bias toward continuing the search. This might also explain why theists tend to think teleologically and why atheists tend to suppress it.

There is likely a correlation between morality and intelligence. In GEB, Hofstadter wrote:

It is an inherent property of intelligence that it can jump out of the task which it is performing, and survey what it is done; it is always looking for, and often finding, patterns. (pg. 37)

Over 400 pages later, he repeats this idea:

This drive to jump out of the system is a pervasive one, and lies behind all progress and art, music, and other human endeavors. It also lies behind such trivial undertakings as the making of radio and television commercials. (pg. 478).

It seems to me that McCarthy's third requirement is behind this drive to "jump out" of the system. If a system is to be improved, it must be analyzed and compared with other systems, and this requires looking at a system from the outside.

Earlier, Vox was quoted as saying, "…I believe in evil. I believe in objective, material, tangible evil that insensibly envelops every single one of us sooner or later. I believe in the fallen nature of Man…" The algorithmic pressure to seek new goals is behind Vox's statement. He "knows" that he can be improved -- that he is not what he ought to be. That man is "fallen" is a teleological interpretation of the inner working of the human mind coupled with the notion that god is the ultimate goal. It is this notion that everything is improvable that is behind morality and intelligence and, coupled with self-awareness, is what makes us human.

Given that morality arises from introspection of our goal seeking behavior, what goals should we seek? That will be the subject of the next post.

[1] Is Theology Poetry, see Argument from reason.

[2] "When I am Dead" in Possible Worlds (1927)

[3] The Mechanism of Morality

[4] Moral judgments can be altered ... by magnets

[5] The Is-Ought Problem Considered As A Question Of Artificial Intelligence

[6] “Our moral judgments are not the result of a single process, even though they feel like one uniform thing,” she says. “It’s actually a hodgepodge of competing and conflicting judgments, all of which get jumbled into what we call moral judgment.”4

Theism vs. Atheism: A Debate?

It is common wisdom that "you can't prove a negative." Strictly speaking, this isn't true. Some negatives can be proven, just like some positives can be proven. Circa 300 B.C.E. Euclid showed that there is no largest prime number. In 1995 Andrew Wiles proved Fermat's Last Theorem, which says that there are no integers, x, y, and z > 0 such that xn + yn = zn, where n > 2. But showing that there is no god (or gods) is a more formidable problem. Such a proof would be like showing that no pink unicorns exist -- the only way to do this is by an exhaustive search and, by definition, god supposedly exists outside of nature where man cannot look. In theory, god can only be found if he/she/it actively broke the natural/supernatural barrier and left one or more clues to his existence.

Since I've already mentioned an attribute of god (supernaturalness), Vox has declined to define "god or gods" and has referred to dictionary definitions. I have no interest in arguing for or against beings that are worshipped (which says more about the worshipper than the worshipped), or beings greater than man that have power over nature (cf. Star Trek's Who Mourns for Adonis? where Kirk and crew run into Apollo). I will limit my arguments to a supernatural being who created nature. This could be the god of the three main monotheistic religions; it could also be a deistic god or alien scientists who are running our universe as a simulation in one of their computers (many implies one).

How then, to make the case for atheism? Bertrand Russell, in "The Problems of Philosophy", states that all knowledge is based on instinctive beliefs (pg. 25). Aside from cogito, ergo sum I'm not aware of a catalog of basic beliefs (I'm a software engineer, not a philosopher). Is "there is/is not a god" a basic belief, or is it a derived position? I will argue that both positions are basic beliefs, accepted without proof. Given two axiomatic systems, which one is right? The problem is like that of geometry. Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometry have the same number of axioms -- five -- but the fifth axiom is different in each. Each geometry is consistent. Which geometry corresponds to the universe we live in? On a very small scale, the universe is Euclidean (i.e. space is flat). But for the entire universe, we don't know, because we don't know the mass of the universe. To make the case for atheism, then, it must be shown that atheism is consistent and that it corresponds to the universe we live in.

Informally, both atheism and theism are consistent, in that neither axiom results in a statement that asserts a contradiction. There are claimed contradictions, for example, the problem of evil supposedly contradicts the existence of a loving god. Likewise, the problem of good has been used to argue against the non-existence of God. But neither hold up to scrutiny. Both systems result in explanations for all natural phenomena, even though those explanations may be wildly different. Does atheism correspond to the universe? That's a difficult question since we have incomplete knowledge. For example, if it could be shown that life could not arise by natural processes, then atheism would fail the correspondence test. This is, I think, one of two weakness of atheism and is what caused the formerly leading atheist thinker Antony Flew to convert to deism in 2004 before his death in 2010. However, this is a position adopted from ignorance informed by incredulity. There is no shame in saying, "we don't know," since incomplete knowledge is a problem in both systems, and the argument from incredulity is a logical fallacy recognized by both sides.

The arguments for theism typically fall into one of four categories:

- The problem of origins - God is needed to get things going.

- The problem of thought - materialism cannot account for human thought.

- The problem of morality - Vox wrote in "Letter to Common Sense Atheism I", "Why am I a Christian? Because I believe in evil. I believe in objective, material, tangible evil that insensibly envelops every single one of us sooner or later. I believe in the fallen nature of Man…"

- The problem of personal testimony/transformation - God did such and such in someone's life. For a powerful example of such testimony, see John C. Wright's "A Question I Never Tire of Answering". Vox said much the same thing, himself. I, too, have been on the road to Damascus. This would include the category of miracles including, but not limited to, the Resurrection of Jesus and fulfilled prophecy.

- We are partially self-aware. Our self-awareness is partial because it doesn't fully extend to how our brains work. For example, we make decisions, but we can't see the mechanism by which those decisions actually come about. This study, for example, shows how analysis of brain wave patterns enable prediction of decisions before the test subjects were aware of what they were going to do.

- Our brains are wired to look for patterns.

- Most brains are wired to think teleologically, that is to ascribe meaning to external events. As shown by this study, theists think teleologically, atheists think teleologically but then suppress it, and people with Asperberger's do not think teleologically. Their wiring prevents it. See also the work of Catherine Caldwell-Harris of Boston University. Note that this describes typical behavior; individuals may vary.

- Our brains are goal-seeking engines with variable goals. Animals are wired for reproduction and, to support reproduction, have the sub-goals of feeding, fighting, and fleeing. Man, however, is a general purpose problem solver and, according to John McCarthy in Programs with Common Sense, one feature to enable this behavior is that "All aspects of behavior except the most routine must be improvable. In particular, the improving mechanism should be improvable."

- We are "selfish" organisms, that is, our default behavior is to maximize our long-term benefit.

Earlier, I said that both theism and atheism were basic beliefs. C and D show why theism is, for most, a basic belief. It's how most brains are wired. C by itself explains the belief that many gods exist (many things need explanation), D explains monotheism (a goal seeking engine without a fixed goal will imagine an ultimate goal). God belief is also comforting because it can always be used for explanations where our knowledge is incomplete (there is ultimate meaning, ultimate morality, ultimate cause). Atheism is, likewise, a basic belief since it cannot be shown to be true. The atheist claim that there is no evidence for god is misguided, since belief guides the evaluation of evidence. This also applies to the theist.

If this is so, then why the debate? Partly because of the challenge. Partly because I detest bad arguments -- from either side. Proverbs 27:17 says, "Iron sharpens iron, and one person sharpens the wits of another." Christians have become dull over time and need a wakeup call. Partly because I think I may have some new insights to offer, particularly since computer science is still in its infancy and I think it has important things to say with respect to theology. And partly because I think the result will be surprising. My position actually contains the seed of its own destruction (earlier, I said that atheism has two weaknesses) but I'm not going to give it away.

[1] Dominic Saltarelli eventually volunteered.

Atheism and Evidence, Redux

Today, I came across the article "Does Secularism Make People More Ethical?" The main thesis of the article is nonsense, but it does reference work by Catherine Caldwell-Harris of Boston University. Der Spiegel (The Mirror) said:

Boston University's Catherine Caldwell-Harris is researching the differences between the secular and religious minds. "Humans have two cognitive styles," the psychologist says. "One type finds deeper meaning in everything; even bad weather can be framed as fate. The other type is neurologically predisposed to be skeptical, and they don't put much weight in beliefs and agency detection."

Caldwell-Harris is currently testing her hypothesis through simple experiments. Test subjects watch a film in which triangles move about. One group experiences the film as a humanized drama, in which the larger triangles are attacking the smaller ones. The other group describes the scene mechanically, simply stating the manner in which the geometric shapes are moving. Those who do not anthropomorphize the triangles, she suspects, are unlikely to ascribe much importance to beliefs. "There have always been two cognitive comfort zones," she says, "but skeptics used to keep quiet in order to stay out of trouble."

This broadly agrees with the Scientific American article, although it isn't clear if the non-anthropomorphizing group is thinking teleologically, but then suppressing it (which is characteristic of atheists) or not seeing meaning at all (characteristic of those with Asperger's).

Caldwell-Harris' work buttresses the thesis of Atheism: It isn't about evidence.

Too, her work is interesting from a perspective in artificial intelligence. One purpose of the Turing Test is to determine whether or not an artificial intelligence has achieved human-level capability. Her "triangle film" isn't dissimilar from a form of Turing Test since agency detection is a component of recognizing intelligence. If the movement of the triangles was truly random, then the non-anthropomorphizing group was correct in giving a mechanical interpretation to the scene. But if the filmmaker imbued the triangle film with meaning, then the anthropomorphizing group picked up a sign of intelligent agency which was missed by the other group.

I wrote her and asked about this. She has absolutely no reason to respond to my query, but I hope she will.

Finally, I have to mention that the Der Spiegel article cites researchers that claim that secularism will become the majority view in the west, which contradicts the sources in my blog post. On the one hand, it's a critical component of my argument. On the other hand, I just don't have time for more research into this right now.

C. S. Lewis: Evolutionary Hymn

Lead us, Evolution, lead us

Up the future's endless stair;

Chop us, change us, prod us, weed us.

For stagnation is despair:

Groping, guessing, yet progressing,

Lead us nobody knows where.

Wrong or justice, joy or sorrow,

In the present what are they

while there's always jam-tomorrow,

While we tread the onward way?

Never knowing where we're going,

We can never go astray.

To whatever variation

Our posterity may turn

Hairy, squashy, or crustacean,

Bulbous-eyed or square of stern,

Tusked or toothless, mild or ruthless,

Towards that unknown god we yearn.

Ask not if it's god or devil,

Brethren, lest your words imply

Static norms of good and evil

(As in Plato) throned on high;

Such scholastic, inelastic,

Abstract yardsticks we deny.

Far too long have sages vainly

Glossed great Nature's simple text;

He who runs can read it plainly,

'Goodness = what comes next.'

By evolving, Life is solving

All the questions we perplexed.

On then! Value means survival-