February 2011

Modeling Morality: The End of Time

Modeling Morality presented six views of how morality is typically imagined to work. For the most part, I wanted the diagrams to speak for themselves. The intent was not to argue for or against any particular model, but to provide a framework for future explorations. However, I did provide reasons for why model #6 should be preferred to model #4, because in my experience most Christians tend to think model #4 accurately represents the Biblical view. I noted that model #4 “is not suitable for this phase of history.”

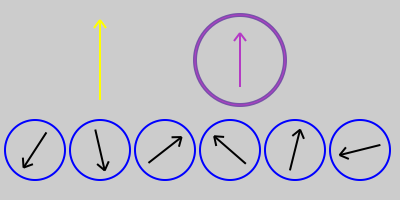

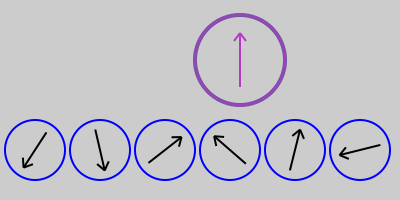

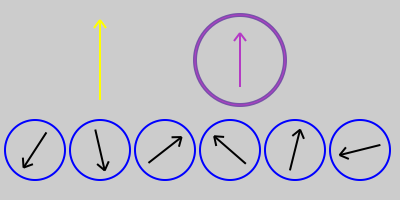

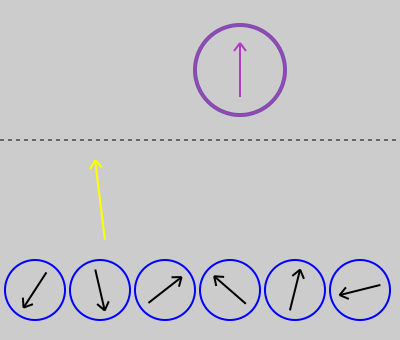

Since I hinted at a change of models, I need to present what I think the model will be when God’s kingdom is fully come:

I think Lewis, and model #7, both accurately reflect the Biblical view of the eternal state.

Since I hinted at a change of models, I need to present what I think the model will be when God’s kingdom is fully come:

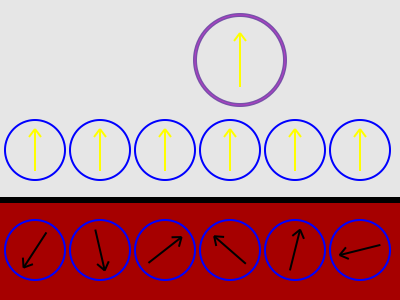

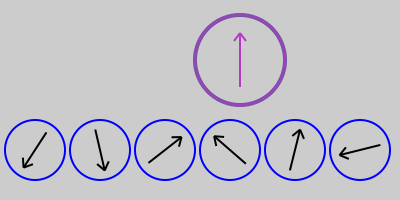

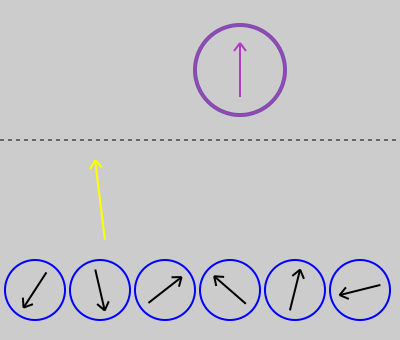

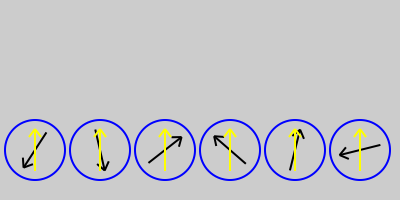

Model #7

The dashed line in model #6 disappears, reminiscent of Revelation 21:1, where St. John wrote, “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more.” The sea, of course, does not refer to a literal body of water, but the “sea of glass, like crystal” that separates the throne of God in heaven from earth [Rev 4:6].

The thick black line in model #7 represents the “great chasm” of Luke 16:26. Below the line are those who have clung to their will. As C. S. Lewis wrote in The Great Divorce:

There are only two kinds of people in the end: those who say to God, “Thy will be done,” and those to whom God says, in the end, “Thy will be done.”

I think Lewis, and model #7, both accurately reflect the Biblical view of the eternal state.

1 Comment

Modeling Morality

Previous posts (1, 2, and 3) presented several visual models of morality from atheistic and theistic perspectives. These posts used a definition of morality as being an ill-defined “distance” measurement between “is” and “ought.” Based on the subsequent article The Mechanism of Morality, I’ve revised the definition. Morality is how self-aware agents describe searches through goal space to a goal state. Something that leads to a goal state is considered good, while something that leads away from a goal state is considered bad. Whether or not a goal state is good depends on its relation to other goal states. If there are ultimate goal states (whatever they might be), then there are ultimate goods.

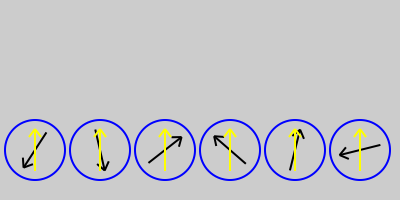

Here, six different models are presented. Three are from an atheistic worldview and three are from a theistic worldview. An arrow represents the direction and location of a “moral compass,” which represents goal states that are deemed to be “good.” The arrows, being static, may suggest a fixed moral compass. At least for humans, we don’t have fixed goals (cf. here and here), so that a moving arrow might be a better representation. However, I’m not going to use animation with these pictures.

These models will be used in later posts when examining various arguments that have a moral basis, since in many cases, the model is assumed and an incorrect model will lead to an incorrect argument. Of course, this begs the question of which model corresponds to reality.

The first three models assume an atheistic worldview.

Model #1

Model #1

The first model is simple: morality is internal to self-aware goal seeking agents. There is no external standard of morality, since there is no purpose to the universe.

Model #2

Model #2

This model just adds an external moral standard. What that standard might be isn’t specified here and is the subject of much speculation elsewhere. In the model, no agent’s moral compass aligns with the external standard, reflective of the human condition that we don’t always choose goals that we know we should.

If morality is related to goal seeking behavior, then what might be the goal(s) of nature? Why should any other moral agent conform to the external standard?

Model #3

Model #3

Here, a common moral standard is not found in “nature,” but is internal to each agent. It reflects the idea that man is basically born “good,” but, over time, drifts from a moral ideal. As before, it reflects the common experience that we don’t choose what we ought to choose.

The next three models reflect various theistic views.

Model #4

Model #4

This model reflects that God, and only God, defines what is good and that such goodness is internal to God. Moral agents are expected to align their compasses with God’s. Either God reveals His moral compass to man, or man can somehow discern God’s moral compass through the construction of nature. I will argue that this model is not suitable for this phase of history when model #6 is presented.

Model #5

Model #5

This model adds an external standard to which both God and moral agents should conform. This view of the model shows a “good” god, i.e. one who always conforms to the external standard. This model is frequently assumed in arguments that try to show that God is morally wrong, by attempting to show that God’s moral compass is not aligned with some external standard.

This model, regardless of the orientation of the external compass, is a flawed model (at least in Christian theology) since God is not subject to any external standard. This should be obvious since everything “external” to God was created by God and is therefore subject to Him.

Model #6

Model #6

In this model, God exists apart from all other moral agents and is the source of His moral compass. Within creation, however, He has decreed a moral standard to which moral agents should conform. In terms of goal space, His goals are not always our goals.

I think that the Bible makes it clear that:

Similarly, Leviticus 19:18 says, “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.” God reserves vengeance for Himself: “Vengeance is mine, I will repay.” [Heb 10:30].

That this model is correct from a Bible perspective should be more obvious than it is; after all, we “see through a glass darkly.” He is God and we are not. The Creator sets the goals/rules for His creation; yet He has His own goals/rules.

These models provide a framework for how various answers to questions about morality arise. Consider the question, “Is the difference between good and bad whatever God says it is? Or is God good because he conforms to a standard of goodness?” Note that this question is really asking “what is correct model of theistic morality?”

With model #4, the answer would be “God is good because He Himself is the standard for goodness.”

With model #5, the answer is “He conforms to a standard of goodness.”

With model #6, the answer is “both.” For us, the difference between good and evil is whatever God says it is. For God, He is His own standard of goodness. He determines the goals we are to pursue and, in this life, those goals aren’t necessarily the goals He pursues for Himself.

Here, six different models are presented. Three are from an atheistic worldview and three are from a theistic worldview. An arrow represents the direction and location of a “moral compass,” which represents goal states that are deemed to be “good.” The arrows, being static, may suggest a fixed moral compass. At least for humans, we don’t have fixed goals (cf. here and here), so that a moving arrow might be a better representation. However, I’m not going to use animation with these pictures.

These models will be used in later posts when examining various arguments that have a moral basis, since in many cases, the model is assumed and an incorrect model will lead to an incorrect argument. Of course, this begs the question of which model corresponds to reality.

The first three models assume an atheistic worldview.

The first model is simple: morality is internal to self-aware goal seeking agents. There is no external standard of morality, since there is no purpose to the universe.

This model just adds an external moral standard. What that standard might be isn’t specified here and is the subject of much speculation elsewhere. In the model, no agent’s moral compass aligns with the external standard, reflective of the human condition that we don’t always choose goals that we know we should.

If morality is related to goal seeking behavior, then what might be the goal(s) of nature? Why should any other moral agent conform to the external standard?

Here, a common moral standard is not found in “nature,” but is internal to each agent. It reflects the idea that man is basically born “good,” but, over time, drifts from a moral ideal. As before, it reflects the common experience that we don’t choose what we ought to choose.

The next three models reflect various theistic views.

This model reflects that God, and only God, defines what is good and that such goodness is internal to God. Moral agents are expected to align their compasses with God’s. Either God reveals His moral compass to man, or man can somehow discern God’s moral compass through the construction of nature. I will argue that this model is not suitable for this phase of history when model #6 is presented.

This model adds an external standard to which both God and moral agents should conform. This view of the model shows a “good” god, i.e. one who always conforms to the external standard. This model is frequently assumed in arguments that try to show that God is morally wrong, by attempting to show that God’s moral compass is not aligned with some external standard.

This model, regardless of the orientation of the external compass, is a flawed model (at least in Christian theology) since God is not subject to any external standard. This should be obvious since everything “external” to God was created by God and is therefore subject to Him.

In this model, God exists apart from all other moral agents and is the source of His moral compass. Within creation, however, He has decreed a moral standard to which moral agents should conform. In terms of goal space, His goals are not always our goals.

I think that the Bible makes it clear that:

- God is not only “good,” but He defines “goodness.”

- There are “goods,” as shown by His behavior, that man is not permitted to pursue. That is, what is good for God isn’t necessarily good for man, which would be the case if there were a common moral compass.

Similarly, Leviticus 19:18 says, “You shall not take vengeance or bear a grudge against any of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself: I am the LORD.” God reserves vengeance for Himself: “Vengeance is mine, I will repay.” [Heb 10:30].

That this model is correct from a Bible perspective should be more obvious than it is; after all, we “see through a glass darkly.” He is God and we are not. The Creator sets the goals/rules for His creation; yet He has His own goals/rules.

These models provide a framework for how various answers to questions about morality arise. Consider the question, “Is the difference between good and bad whatever God says it is? Or is God good because he conforms to a standard of goodness?” Note that this question is really asking “what is correct model of theistic morality?”

With model #4, the answer would be “God is good because He Himself is the standard for goodness.”

With model #5, the answer is “He conforms to a standard of goodness.”

With model #6, the answer is “both.” For us, the difference between good and evil is whatever God says it is. For God, He is His own standard of goodness. He determines the goals we are to pursue and, in this life, those goals aren’t necessarily the goals He pursues for Himself.

New Commenting System

02/13/11 05:50 PM

For I Am Not Ashamed...

02/10/11 09:08 PM Filed in: Christianity | Bad Arguments

Romans 1:16 says, “For I am not ashamed of the gospel; it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who has faith, to the Jew first and also to the Greek.”

One of my pet peeves is when Christians, well meaning though they may be, make a connection between the lifestyle of the one who proclaims the gospel and whether or not the hearer will receive the message. The argument can take many forms: “we have to walk the walk so that we can talk the talk,” “our actions speak louder than words,” “our lifestyle must be consistent with our message,” and so on.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Should our lifestyle be consistent with the message? Of course. As St. Paul wrote, “Shall we continue in sin so that grace may abound? May it never be!” But to say that our actions help or hurt the reception of the gospel is to deny both the grace and the power of God. We readily give lip service to God’s grace toward the hearer; we rightly say that without it no one would ever believe the message. But we forget that God’s grace is likewise bestowed on the speaker. God’s grace overcomes the sin of both the receiver and the sender. In addition, God’s power overcomes our weakness. It is not my place to speak of the sins of others, but the person who was instrumental in presenting the gospel to me wasn’t living what is typically considered to be “the Christian life.” When God took a 2x4 to me, the behavior of someone else didn’t even enter my mind. He demolished all of my objections in an instant.

Ephesians 2:8-9 says, “For by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God--not the result of works, so that no one may boast.” We forget that “not of your own doing” also applies to those whom God uses to proclaim the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus.

One of my pet peeves is when Christians, well meaning though they may be, make a connection between the lifestyle of the one who proclaims the gospel and whether or not the hearer will receive the message. The argument can take many forms: “we have to walk the walk so that we can talk the talk,” “our actions speak louder than words,” “our lifestyle must be consistent with our message,” and so on.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Should our lifestyle be consistent with the message? Of course. As St. Paul wrote, “Shall we continue in sin so that grace may abound? May it never be!” But to say that our actions help or hurt the reception of the gospel is to deny both the grace and the power of God. We readily give lip service to God’s grace toward the hearer; we rightly say that without it no one would ever believe the message. But we forget that God’s grace is likewise bestowed on the speaker. God’s grace overcomes the sin of both the receiver and the sender. In addition, God’s power overcomes our weakness. It is not my place to speak of the sins of others, but the person who was instrumental in presenting the gospel to me wasn’t living what is typically considered to be “the Christian life.” When God took a 2x4 to me, the behavior of someone else didn’t even enter my mind. He demolished all of my objections in an instant.

Ephesians 2:8-9 says, “For by grace you have been saved through faith, and this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God--not the result of works, so that no one may boast.” We forget that “not of your own doing” also applies to those whom God uses to proclaim the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus.

Everything is a remix

Earlier this morning I uploaded “Christian Doctrine, Ancient Egypt, Game Theory”. Also today Daring Fireball posted a link to the very interesting site, Everything Is A Remix. Of course, “everything is a remix” is a remix of “there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9) But, as I noted in Christian Doctrine, Ancient Egypt, Game Theory, Christianity’s golden rule and the admonition to not return evil for good are found in Egyptian culture long before Christ.

Do take a few minutes to watch the two (of four) videos at Everything Is A Remix.

Do take a few minutes to watch the two (of four) videos at Everything Is A Remix.

Christian Doctrine, Ancient Egypt, Game Theory

02/02/11 08:55 AM Filed in: Christianity | Natural Theology

I am slowly making my way through the book Old Testament Parallels by Matthews and Benjamin.

The story “The Farmer and the Courts of Egypt” tells the story of a farmer who is unfairly accused by an official who tries to steal the farmer’s goods. The farmer pleads his case and demands justice. Somewhat reminiscent of the much longer book of Job, it was written around 2134-2040 BCE.

Two passages stand out. The first reads:

Good example is remembered forever. Follow this teaching: “Do unto others, as you would have others do unto you.”

This is the golden rule, over two thousand years before Christ.

The second passage says:

Do not return evil for good...

Proverbs 17:13 says, “Evil will not depart from the house of one who returns evil for good.” Proverbs was likely written after 400 BCE. I find this link to Egyptian thought to be extremely interesting and wonder why I haven’t seen more recognition of this in “mainstream” Christianity. A subsequent post, which has been a very long time in coming, will explore the influence of Egyptian thought on Genesis, the story of Noah, and the Exodus.

In terms of game theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma, “do not return evil for good” translates to “don’t defect after cooperation.”

Both St. Paul and St. Peter write, “Do not repay anyone evil for evil...” [Rom 12:17, 1 Peter 3:19], which becomes “don’t defect at all.”

A future blog post will have to examine the implications of the Christian response to the Prisoner’s Dilemma versus the evolutionarily robust “tit-for-tat” strategy in Axelrod.

The story “The Farmer and the Courts of Egypt” tells the story of a farmer who is unfairly accused by an official who tries to steal the farmer’s goods. The farmer pleads his case and demands justice. Somewhat reminiscent of the much longer book of Job, it was written around 2134-2040 BCE.

Two passages stand out. The first reads:

Good example is remembered forever. Follow this teaching: “Do unto others, as you would have others do unto you.”

This is the golden rule, over two thousand years before Christ.

The second passage says:

Do not return evil for good...

Proverbs 17:13 says, “Evil will not depart from the house of one who returns evil for good.” Proverbs was likely written after 400 BCE. I find this link to Egyptian thought to be extremely interesting and wonder why I haven’t seen more recognition of this in “mainstream” Christianity. A subsequent post, which has been a very long time in coming, will explore the influence of Egyptian thought on Genesis, the story of Noah, and the Exodus.

In terms of game theory and the Prisoner’s Dilemma, “do not return evil for good” translates to “don’t defect after cooperation.”

Both St. Paul and St. Peter write, “Do not repay anyone evil for evil...” [Rom 12:17, 1 Peter 3:19], which becomes “don’t defect at all.”

A future blog post will have to examine the implications of the Christian response to the Prisoner’s Dilemma versus the evolutionarily robust “tit-for-tat” strategy in Axelrod.