Synchronicity

Fortune favors...

05/18/22 08:47 AM

Fate protects fools, little children, and ships named Enterprise.1

We had planned to leave Friday morning to drive to Texas to see the grandkids. On Thursday night our daugther-in-law informs us that she has tested positive for COVID. We quickly shift gears to spend a few days at Myrtle Beach. I then realize that I hadn't yet refilled my prescription medicine. Had we left Friday as planned I would have been without my blood pressure medicine.

Walking on the beach this morning, having turned around at the half-way point of 4,600 steps, I noticed a piece of trash on the shore. As I bent down to pick it up, I noticed that it looked like a room keycard. It was a room keycard. Mine. It must have fallen out of my pocket one of the times when I checked my phone.

Last night we ate at Pizza Chef Gourmet Pizza which is near the Seawatch Resort where we are staying. It's a little hole-in-the-wall place that we ate at the last time we were here (pre-COVID). The pizza crust is one of the best I've ever had.

[1] William T. Riker, "Contagion", ST:TNG S02E11

Comments

Trinity: Full Circle

09/19/19 04:03 PM

For just a little over two years I have been discussing the doctrine of the Trinity with a friend who has misgivings about it. One of the issues that we've gone back and forth on is whether or not the writers of Scripture should have had the same understanding of the Trinity that we do today. He thinks the answer has to be "yes", since they were inspired by the Holy Spirit to write what they did about Jesus. I think the answer is "no", for two reasons. First, the writers of Scripture wrote over a period of years. What one author wrote might not have been available to another author, and the doctrine of the Trinity comes out of the entirety of statements about Christ. Second, in some ways, God and Nature are alike. Both appear to have an unchangeable core (for Nature, as far as we can currently ascertain, physical law and physical constants haven't changed). But while Nature has always presented the same "face" to us, we are still learning about it. The 20th century saw two great revolutions in our understanding: General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics. How we understand the world today is very different from that of Einstein (while he developed Relativity, he didn't like Quantum Mechanics), Newton, Copernicus, and Aristotle. We remain puzzled over dark matter and dark energy, so our understanding tomorrow will be different. Yet Nature hasn't changed. Nature has always revealed what Nature is. God, on the other hand, progressively revealed Himself to us, culminating in the revelation of His Son. Yet, as with Nature, it has still taken us time to digest what has been said. One of the biggest impediments to understanding Relativity, Quantum Mechanics, and the Trinity, is our intuition. All three are counter-intuitive and we have trouble accepting that. That's a story for another time.

But I digress. Our church is considering hiring an assistant pastor who went to Wheaton. In 2015, Wheaton initiated termination proceedings against tenured professor Larycia Hawkins. I blogged about it here. Since I'm a troublemaker, I plan on asking the candidate his opinion on the whole matter and whether or not he agrees with Wheaton's position. I hope he doesn't, because I think Wheaton is very much wrong. In reviewing my post, I decided to bring some (but not all) stale links up to date. One of the links was to her response to Wheaton. Since that link, to Scribd, now requires a subscription to view fully, I managed to find it elsewhere. In it, she wrote:

Dr. Hawkins supports my position that our understanding of Christ has been progressive. I texted this to my friend. His response was that my post on Dr. Hawkins was the first link I ever sent him.

But I digress. Our church is considering hiring an assistant pastor who went to Wheaton. In 2015, Wheaton initiated termination proceedings against tenured professor Larycia Hawkins. I blogged about it here. Since I'm a troublemaker, I plan on asking the candidate his opinion on the whole matter and whether or not he agrees with Wheaton's position. I hope he doesn't, because I think Wheaton is very much wrong. In reviewing my post, I decided to bring some (but not all) stale links up to date. One of the links was to her response to Wheaton. Since that link, to Scribd, now requires a subscription to view fully, I managed to find it elsewhere. In it, she wrote:

On the "yes" side, both Christians and Muslims (as well as Jews) confess that God is One (Deut. 6:4). So, yes, Christians and Muslims (and Jews) affirm fully that "that God is the Father of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob" but –borrowing from Stackhouse--"if we insist, as many are insisting in this furore, that God must be understood in terms of the Trinity, with a focus especially on Jesus, or else one really doesn't know God, I respectfully want to ask such Bible believers what they make of Abraham (who is held up as a paradigm of faith in the New Testament) and the list of Old Testament saints (who are held up as paradigms of faith to Christians in Hebrews 11), precisely none of whom can be seriously understood as holding trinitarian views and some proleptic vision of the identity and career of Jesus Christ."

Dr. Hawkins supports my position that our understanding of Christ has been progressive. I texted this to my friend. His response was that my post on Dr. Hawkins was the first link I ever sent him.

Hope

02/03/18 03:32 PM

During lunch today I was listening to a video featuring Jordan Peterson and Ben Shapiro. Between 16:35 and 16:52 in the video, Peterson remarks:

"Well, it's partly because the problem with … the problem with relativism let's say … let's say that did produce a radical state of equality. Well the problem with that is that there's no "up". And the problem with there being no "up" is there's no hope. And the problem with that is that people actually live on hope."

Dogs, too.

My granddog, Titan, lives by hope. Hope that he will get treats, especially after going for a walk or when I come home. Here he is, live and unrehearsed, when I arrived home from lunch. He greets me at the door to the garage, then stops where we keep his treats in a niche above his food and water bowls. As I go by, he hopes that he'll get a bit of the waffles my wife made this morning.

I can't ever disappoint my dog.

Mlem.

Drive fast and eat cheese!

03/17/15 06:36 PM

You know what we should do right now? Run out of here, grab a couple of horses, ride bareback through the woods all night, and make love in a meadow at sunrise. ... Let's live. Let's taste danger. Let's go for the gusto, consequences be damned. Let's drive fast and eat cheese!—S1E8

It was a Mexican restaurant. I had cheese.

Dialog With An Atheist #2

01/02/15 05:51 AM

John Loftus wrote:

Second, by your criteria, I should throw out the American Constitution and Quantum Mechanics. I should throw out the American Constitution because there is no universal agreement on what the 2nd amendment means. Even the Supreme Court was divided, 5-4, on whether or not the 2nd Amendment guarantees the right of individuals to own firearms.

And we should throw out Quantum Mechanics, because while most everyone agrees on Schrödinger's equation, there is widespread disagreement on how to interpret it. Copenhagen, Many-worlds, De Broglie-Bohm, ... You might enjoy the articles Lubos Motl posts about idiot scientists who say idiotic things about science. This one is a recent one about a paper published in Nature. And this one about proponents of the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics…

So there are ambiguities. So what? That's true of anything, whether it is interpretation of Christian doctrine, interpretation of the American Constitution, or interpretation of nature.

It's how our neural nets work.

Shall we declare science wrong because scientists can't agree on how to interpret nature via quantum mechanics?

Go back and re-read what I wrote. As a mathematician, I will say that we cannot escape our axioms. What we believe controls how we evaluate evidence. Then I said that I think that atheism is a consistent, complete worldview. I also said that Christianity is a consistent, complete worldview.

That doesn't mean that there aren't inconsistent Christians, or inconsistent Atheists. im-skeptical is an inconsistent atheist. He could be a consistent atheist, but whether or not he has that eureka moment only time will tell.

So what? If I have to weigh intellect against intellect, I'd certainly put C. S. Lewis ahead of John Loftus, or Bart Ehrman.

But what you don't understand is that I'm not playing that game. Atheism vs. Christianity isn't about evidence. It never has been. It's about how brains process evidence.

How about you?

And that you commit the fallacy of "selective citing" only shows how bankrupt your argument is. Note that this doesn't prove that Christianity is right and atheism is wrong. It just proves that you are an ignorant atheist, as opposed to an intelligent atheist.

And, for the last time, you're trying to argue evidence with someone who says that it isn't about the evidence. After all, if both Christianity and atheism are complete consistent systems, there isn't any evidence that can possibly exist to settle the argument one way or another.

wrf3, I've been reading your comments with some interest. You represent the kind of person who intrigues me.

Thank you?

Since I never know what spark can be ignited that will eventually start a fire of knowledge and understanding free of brainwashing, here goes.

I just love it how you automatically poison the well by using emotive terms like "brainwashing." We poor dumb biased Christians have been brainwashed, while you objective rational clear-thinking atheists have broken free. Just pathetic.

Does is bother you that you come across as having the whole truth and nothing but the truth--that you have all the answers? It should.

It doesn't, for the simple reason that "how I come across" is based more on your incomplete perception of me, rather than how I actually am. We all know that, in these politically correct times, offense can be taken where none was either intended, or given. In the same way, I suspect you're reading more into my responses than what I've actually written.

For the more a person knows the less s/he claims to know. Tell us what you don't know pertaining to religious truth, if you want to prove me wrong.

That would fill a book. Shall I write another book about what I don't know about mathematics, even though I have a degree in math? How about a book about what I don't know about science, even though my math degree is from an engineering school, so I've had to take physics, chemistry, biology, thermodynamics, circuits and devices, astronomy, materials science, …?

I'll be curious to learn if you admit ignorance about several important basic details of your particular religious worldview, while at the same time claiming certainty about the whole worldview itself. That would be odd wouldn't you think, if you admit ignorant of the foundational details but certain of the whole?

First, you tell me what the "foundational details" you think I'm ignorant of. Because we may disagree on what is foundational and what is derived.

Second, by your criteria, I should throw out the American Constitution and Quantum Mechanics. I should throw out the American Constitution because there is no universal agreement on what the 2nd amendment means. Even the Supreme Court was divided, 5-4, on whether or not the 2nd Amendment guarantees the right of individuals to own firearms.

And we should throw out Quantum Mechanics, because while most everyone agrees on Schrödinger's equation, there is widespread disagreement on how to interpret it. Copenhagen, Many-worlds, De Broglie-Bohm, ... You might enjoy the articles Lubos Motl posts about idiot scientists who say idiotic things about science. This one is a recent one about a paper published in Nature. And this one about proponents of the many worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics…

Let melink to a few items for your reflection on this question. ... Christians debate many doctrinal and foundational specifics, as seen in these books. Are you claiming to know the answers for every issue?

Of course not. Ask me which eschatological view I hold. On Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays I prefer amillennialism. On Thursdays I like postmillennialism. On Fridays I reflect on partial preterism. On Saturdays, I consider historic dispensationalism.

So there are ambiguities. So what? That's true of anything, whether it is interpretation of Christian doctrine, interpretation of the American Constitution, or interpretation of nature.

It's how our neural nets work.

Shall we declare science wrong because scientists can't agree on how to interpret nature via quantum mechanics?

In one of these above books, on apologetics, several authors argue against presuppositionalism. I suppose you are certain they are wrong too, correct?

If by "presuppositionalism" you mean "Christian presuppositionalism" then, yes, they are wrong.

Go back and re-read what I wrote. As a mathematician, I will say that we cannot escape our axioms. What we believe controls how we evaluate evidence. Then I said that I think that atheism is a consistent, complete worldview. I also said that Christianity is a consistent, complete worldview.

That doesn't mean that there aren't inconsistent Christians, or inconsistent Atheists. im-skeptical is an inconsistent atheist. He could be a consistent atheist, but whether or not he has that eureka moment only time will tell.

See a trend here? You are correct. Every other Christian is wrong. Seriously?

Only in your imagination.

The historical trend is also telling, ...

Are you saying that truth is determined by numbers? Really? And 100, or 200, or 1,000 years from now, when the trend has changed, will your great-great-great grandchildren try to use the same argument?

There are several former believers who no longer believe. ... Have you read these works?

Some of them. On the other hand, there are former atheists who now believe. Me, for one. C. S. Lewis, for another.

So what? If I have to weigh intellect against intellect, I'd certainly put C. S. Lewis ahead of John Loftus, or Bart Ehrman.

But what you don't understand is that I'm not playing that game. Atheism vs. Christianity isn't about evidence. It never has been. It's about how brains process evidence.

Let's say that it's possible you are wrong.

I'm a software engineer. I'm also married. I'm wrong a thousand times a day.

Wouldn't you want to know? No, seriously, wouldn't you want to know, yes or no?

Of course I would.

How about you?

You have Christians debunking themselves, where the trend is from conservatism to atheism, with several former intellectual believers several rejecting your faith and writing about it.

Truth has never, ever been about numbers. That you even try this argument means that you don't know how epistemology works. You're exhibiting the "r" side of r/K selection traits (i.e. where group consensus is more important than anything else).

And that you commit the fallacy of "selective citing" only shows how bankrupt your argument is. Note that this doesn't prove that Christianity is right and atheism is wrong. It just proves that you are an ignorant atheist, as opposed to an intelligent atheist.

Wouldn't you want to know why this is the case? Satan is too easily an answer. You would not accept that as an answer if someone said YOUR theology was of Satan, would you?

Why don't you let me provide my own answers? Otherwise, you can just have a conversation with yourself and whatever straw-men you want to talk to.

My claim is that doubt should be the position of everyone until such time as the evidence shows otherwise.

A self-defeating philosophy if ever there was one because, if you really believed it, you would doubt it and enter into a vicious circle.

And, for the last time, you're trying to argue evidence with someone who says that it isn't about the evidence. After all, if both Christianity and atheism are complete consistent systems, there isn't any evidence that can possibly exist to settle the argument one way or another.

The Regulative Principle

10/18/14 09:08 PM

Yesterday, we went to see the house that son and daughter-in-law are buying. It's about 1.5 hours away with rush hour traffic. We drove past a small "Primitive Baptist" church. In this day and age, "primitive" is usually taken to mean "primitive with respect to technology," such as with the Amish and their simple lifestyles, or Jehovah's Witnesses and their refusal of blood transfusions. But the "primitive" in "Primitive Baptist" refers to theology with the claim that their doctrines are those held by the early church. Their worship practices are influenced by the idea that if something isn't commanded in Scripture then it should not be done. For example, as there is no positive command to use musical instruments in worship, most Primitive Baptist churches do not use them. They also reject the idea of "Sunday school" as well as seminaries.

Read More...

Read More...

Quantum Mechanics and Reformation Theology

09/15/13 01:30 PM

We're studying the foundations of Reformation theology in Sunday school. I find myself having to bite my tongue and not always succeeding. However, on the following two points, I've managed to stay quiet.

Several weeks ago, the teacher stated (paraphrasing) that "we believe 2+2=4 because of the axioms of mathematics." However, in "Quantum Computing Since Democritus", on page 10, Aaronson writes:

How can we state axioms that will put the integers on a more secure foundation, when the very symbols and so on that we're using to write down the axioms presuppose that we already know what the integers are?

Well, precisely because of this point, I don't think that axioms and formal logic can be used to place arithmetic on a more secure foundation. If you don't already agree that 1+1=2, then a lifetime of studying mathematical logic won't make it any clearer!

Today, in passing, it was said that responsibility necessitates the free will of man. Nothing could be further from the truth. I continued my reading of Aaronson during lunch today and came across this gem on pages 290-291:

Before we start, there are two common misconceptions that we have to get out of the way. The first one is committed by the free will camp, and the second by the anti-free-will camp.

The misconception committed by the free will camp is the one I alluded to before: if there's no free will, then none of us are responsible for our actions, and hence (for example) the legal system would collapse….

Actually, I've since found a couplet by Ambrose Bierce that makes the point very eloquently:

"There's no free will," says the philosopher;

"To hang is most unjust."

"There is no free will," assent the officers.

"We hang because we must."

Looking ahead to the end of the chapter, Aaronson brings Conway's "Free-Will Theorem" into play. What he doesn't apparently discuss (I've just scanned here and there), is that this randomness is not under our control.

Several weeks ago, the teacher stated (paraphrasing) that "we believe 2+2=4 because of the axioms of mathematics." However, in "Quantum Computing Since Democritus", on page 10, Aaronson writes:

How can we state axioms that will put the integers on a more secure foundation, when the very symbols and so on that we're using to write down the axioms presuppose that we already know what the integers are?

Well, precisely because of this point, I don't think that axioms and formal logic can be used to place arithmetic on a more secure foundation. If you don't already agree that 1+1=2, then a lifetime of studying mathematical logic won't make it any clearer!

Today, in passing, it was said that responsibility necessitates the free will of man. Nothing could be further from the truth. I continued my reading of Aaronson during lunch today and came across this gem on pages 290-291:

Before we start, there are two common misconceptions that we have to get out of the way. The first one is committed by the free will camp, and the second by the anti-free-will camp.

The misconception committed by the free will camp is the one I alluded to before: if there's no free will, then none of us are responsible for our actions, and hence (for example) the legal system would collapse….

Actually, I've since found a couplet by Ambrose Bierce that makes the point very eloquently:

"There's no free will," says the philosopher;

"To hang is most unjust."

"There is no free will," assent the officers.

"We hang because we must."

Looking ahead to the end of the chapter, Aaronson brings Conway's "Free-Will Theorem" into play. What he doesn't apparently discuss (I've just scanned here and there), is that this randomness is not under our control.

Crime and Vocabulary

06/23/13 04:48 PM

I was surfing the web on Thursday and a link let me to a post on 27bslash6 that I hadn't yet read. There I came across the word apophenia which I wasn't familiar with. Apophenia is the experience of seeing meaningful patterns in random data. I'm familiar with the concept as it is discussed in the very excellent book The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives although the word apophenia isn't used. At least it isn't in the index. Our brains are constantly looking for patterns, whether a tree, an amplifier, or a friend's face. But we also see things that aren't there, as anyone who has looked at a Rorschach ink blot or an optical illusion can attest. On Saturday, SlashDot reported that Google had analyzed their data concerning the effectiveness of their interview process and came to the sobering conclusion that there was no relationship between their interview techniques and employee performance. Business practices based on apophenia.

Friday comes between Thursday and Saturday and therein lies a tale... Read More...

Friday comes between Thursday and Saturday and therein lies a tale... Read More...

Sproul and Bradbury on Hedonism

07/01/12 06:16 PM

After reading The Consequences of Ideas by R. C. Sproul, in remembrance of the recent passing of Ray Bradbury, I read Dandelion Wine.

Concerning hedonism, Sproul wrote:

I noticed the same idea in Dandelion Wine. Leo Auffmann succeeds in building a "happiness machine," but it ultimately fails in delivering on it's promise. Leo's wife, Lena, observes the same paradox of hedonism:

"Did I?"

"Sunsets we always liked because they only happen once and go away."

"But Lena, that's sad."

"No, if the sunset stayed and we got bored, that would be a real sadness. So two things you did you should never had. You made quick things go slow and stay around. You brought things faraway to our backyard where they don't belong, but they just tell you, 'No, you'll never travel, Lena Auffmann, Paris you'll never see! Rome you'll never visit.' But I always knew that, so why tell me? Better forget and make do, we'll make do, eh?"

Concerning hedonism, Sproul wrote:

Epicureans sought to escape the “hedonistic paradox”: The pursuit of pleasure alone ends in either frustration (if the pursuit fails) or boredom (if it succeeds). Both frustration and boredom are kinds of pain, the antithesis of pleasure.

I noticed the same idea in Dandelion Wine. Leo Auffmann succeeds in building a "happiness machine," but it ultimately fails in delivering on it's promise. Leo's wife, Lena, observes the same paradox of hedonism:

"Leo, the mistake you made is you forgot some hour, some day, we all got to climb out of that thing and go back to dirty dishes and the beds not made. While you're in that thing, sure, a sunset lasts forever almost, the air smells good, the temperature is fine. All the things you want to last, last. But outside, the children wait on lunch, the clothes need buttons. And then let's be frank, Leo, how long can youlook at a sunset? Who wants a sunset to last? Who wants perfect temperature? Who wants air smelling good always? So after awhile, who would notice? Better, for a minute or two, a sunset. After that, let's have something else. People are like that, Leo. How could you forget?"

"Did I?"

"Sunsets we always liked because they only happen once and go away."

"But Lena, that's sad."

"No, if the sunset stayed and we got bored, that would be a real sadness. So two things you did you should never had. You made quick things go slow and stay around. You brought things faraway to our backyard where they don't belong, but they just tell you, 'No, you'll never travel, Lena Auffmann, Paris you'll never see! Rome you'll never visit.' But I always knew that, so why tell me? Better forget and make do, we'll make do, eh?"

On The Difference Between Hardware and Software

06/09/12 08:28 PM

The No Free Will Theorem

01/15/12 05:38 AM

In one sense, I'm not ready to write this post; my subconscious mental machinery is still working to sort out all of the ideas in my head. But after not having done any reading for the past few weeks, before bed I picked up where I left off reading Pierce's An Introduction to Information Theory. But I had stopped in the middle of a paragraph, decided I needed to go back to the beginning of the chapter, tried to make progress, and gave up. So I switched to where I had set aside The Best of Gene Wolfe and resumed with the story The Death of Dr. Island. A passage that I will quote later caused a cascade of, if not pieces falling into place, a clarity of what questions to think about.

Earlier this week, over at Vox Popoli, Vox took issue with a particular scientific study that concluded on the basis of experimental data that free will does not exist. While I think I agree that this study does not show what it claims to show, I nevertheless took the approach the free will doesn't exist. The outline of a proof goes like this.

Either thought follows the laws of physics, or it does not. X or ~X. I hold the law of non-contradiction to be true. Now, someone might quibble about percentages: most of the time our thoughts follow the laws of physics, but sometimes they do not. But that misses the point.

Why would anyone suppose that our thoughts don't follow the laws of physics? Perhaps because of an idea that thought is "mystical" stuff; that there is a bit of "god stuff" in our heads that gives us the capabilities that we have. If this were so, since the Christian God transcends nature, our thoughts would transcend nature. It's how we would avoid non-existence upon physical death: the "soul" which is made of "god stuff" returns to God. Perhaps it's due to not knowing how thinking is accomplished in the brain. What I'm about to say certainly isn't taught in any Sunday school I've ever attended, or been discussed in any theological book I've ever read. While that may be because I don't get out enough, I suspect my experience isn't atypical. Another, more general reason, is because that's the way our brains perceive how they operate. It's the "default setting," as it were. Most people, regardless of upbringing, think they have free will. I think I can explain why it's that way, but that's for another post.

How does one prove that thoughts follow the laws of physics? The ultimate test would be to build a human level artificial intelligence. I can't do that. The technology isn't there. Yet. The best I can do is offer a proof of concept. I maintain that this is better than what the proponent of mystical thought can do. I know of no way to build something that doesn't obey the laws of physics. By definition, we can't do it. So any proof would have to come form some source from outside nature held to be authoritative. In my world, that's typically the Bible. There is no end of Bible scholars who hold that Scripture teaches that man has free will. It doesn't, but my intent here is to make may case, not refute their arguments. Although I acknowledge that it certainly wouldn't hurt to do so elsewhere.

What is thought? Thought is matter in motion in certain patterns. This is a key insight which must be grasped. The matter could be photons, it could be water; in our brain it is electrons. The pattern of the flow of electrons is controlled by the neurons in our brain, just like the pattern of the flow of electrons is controlled by NAND gates in a computer. While neurons and NAND gates are different in practice, they are not different in principle. NAND gates can simulate neurons (there are, after all, computer programs that do this) and neurons can simulate NAND gates (cf. here). Another way to view this is that every time a programmer writes computer software, they are embedding thought into matter. I've been programming professionally for almost 40 years and it wasn't until recently that I understood this obvious truth. But if this is so, why aren't there intelligent computers? As I understand it, there are some 100 billion neurons in the brain with some 5 trillion connections. Computers have not yet achieved that level of complexity. Can they? How many NAND gates will it take to achieve the equivalent functionality of 5 trillion neuron connections? I don't know. But the principle is sound, even if the engineering escapes us.

Humans are governed by the laws of quantum mechanics, just as computers are. Having just re-watched all four seasons of Battlestar Galactica on Netflix, it was fascinating to watch the denial of some humans that machines could be their equal, and the denial of some machines that they could be human. In the season 4 episode No Exit, the machine's complaint to his creator "why did you make me like this," is straight out of Romans 9. Art, great art, imitating life.

However one cares to define the concept of "free will," that definition must apply to computers as equally as it does to man. The same principles govern both. As long as it meets that criteria, I can live with silly notions of what "free" means. "You are free to wander around inside this fenced area, but you can't go outside" is usually how the definitions end up. I think limited freedom is an oxymoron, but people want to cling to their illusions.

There is so much more to cover. If our thoughts are the movement of electrons in certain patterns, then how is that motion influenced? What are the feedback loops in the brain? What is the effect of internal stimuli and external stimuli? Is one greater than the other? The Bible exhorts the Christian to place themselves where external stimuli promotes the faith. The dances of their electrons can influence the dance of our electrons. Can we make Christians (or Democrats, or Atheists, or…) through internal modification of brain structures through drugs or surgery? How does God change the path of electrons in those who believe versus those who don't? Would God save an intelligent machine? Could they be "born again"? Does God hide behind quantum indeterminacy? So many questions.

In April 2009, I wrote the post Ecclesiastes and the Sovereignty of God, which gave excepts from the book A Time to Be Born - A Time to Die, by Robert L. Short. Using the Bible, in particular the book of Ecclesiastes, Short reaches the same conclusion I do arguing from basic physics.

The universe controls us. We do not control the universe.

This brings me to the Gene Wolfe quote mentioned at the beginning of this post:

[to be continued]

Earlier this week, over at Vox Popoli, Vox took issue with a particular scientific study that concluded on the basis of experimental data that free will does not exist. While I think I agree that this study does not show what it claims to show, I nevertheless took the approach the free will doesn't exist. The outline of a proof goes like this.

Either thought follows the laws of physics, or it does not. X or ~X. I hold the law of non-contradiction to be true. Now, someone might quibble about percentages: most of the time our thoughts follow the laws of physics, but sometimes they do not. But that misses the point.

Why would anyone suppose that our thoughts don't follow the laws of physics? Perhaps because of an idea that thought is "mystical" stuff; that there is a bit of "god stuff" in our heads that gives us the capabilities that we have. If this were so, since the Christian God transcends nature, our thoughts would transcend nature. It's how we would avoid non-existence upon physical death: the "soul" which is made of "god stuff" returns to God. Perhaps it's due to not knowing how thinking is accomplished in the brain. What I'm about to say certainly isn't taught in any Sunday school I've ever attended, or been discussed in any theological book I've ever read. While that may be because I don't get out enough, I suspect my experience isn't atypical. Another, more general reason, is because that's the way our brains perceive how they operate. It's the "default setting," as it were. Most people, regardless of upbringing, think they have free will. I think I can explain why it's that way, but that's for another post.

How does one prove that thoughts follow the laws of physics? The ultimate test would be to build a human level artificial intelligence. I can't do that. The technology isn't there. Yet. The best I can do is offer a proof of concept. I maintain that this is better than what the proponent of mystical thought can do. I know of no way to build something that doesn't obey the laws of physics. By definition, we can't do it. So any proof would have to come form some source from outside nature held to be authoritative. In my world, that's typically the Bible. There is no end of Bible scholars who hold that Scripture teaches that man has free will. It doesn't, but my intent here is to make may case, not refute their arguments. Although I acknowledge that it certainly wouldn't hurt to do so elsewhere.

What is thought? Thought is matter in motion in certain patterns. This is a key insight which must be grasped. The matter could be photons, it could be water; in our brain it is electrons. The pattern of the flow of electrons is controlled by the neurons in our brain, just like the pattern of the flow of electrons is controlled by NAND gates in a computer. While neurons and NAND gates are different in practice, they are not different in principle. NAND gates can simulate neurons (there are, after all, computer programs that do this) and neurons can simulate NAND gates (cf. here). Another way to view this is that every time a programmer writes computer software, they are embedding thought into matter. I've been programming professionally for almost 40 years and it wasn't until recently that I understood this obvious truth. But if this is so, why aren't there intelligent computers? As I understand it, there are some 100 billion neurons in the brain with some 5 trillion connections. Computers have not yet achieved that level of complexity. Can they? How many NAND gates will it take to achieve the equivalent functionality of 5 trillion neuron connections? I don't know. But the principle is sound, even if the engineering escapes us.

Humans are governed by the laws of quantum mechanics, just as computers are. Having just re-watched all four seasons of Battlestar Galactica on Netflix, it was fascinating to watch the denial of some humans that machines could be their equal, and the denial of some machines that they could be human. In the season 4 episode No Exit, the machine's complaint to his creator "why did you make me like this," is straight out of Romans 9. Art, great art, imitating life.

However one cares to define the concept of "free will," that definition must apply to computers as equally as it does to man. The same principles govern both. As long as it meets that criteria, I can live with silly notions of what "free" means. "You are free to wander around inside this fenced area, but you can't go outside" is usually how the definitions end up. I think limited freedom is an oxymoron, but people want to cling to their illusions.

There is so much more to cover. If our thoughts are the movement of electrons in certain patterns, then how is that motion influenced? What are the feedback loops in the brain? What is the effect of internal stimuli and external stimuli? Is one greater than the other? The Bible exhorts the Christian to place themselves where external stimuli promotes the faith. The dances of their electrons can influence the dance of our electrons. Can we make Christians (or Democrats, or Atheists, or…) through internal modification of brain structures through drugs or surgery? How does God change the path of electrons in those who believe versus those who don't? Would God save an intelligent machine? Could they be "born again"? Does God hide behind quantum indeterminacy? So many questions.

In April 2009, I wrote the post Ecclesiastes and the Sovereignty of God, which gave excepts from the book A Time to Be Born - A Time to Die, by Robert L. Short. Using the Bible, in particular the book of Ecclesiastes, Short reaches the same conclusion I do arguing from basic physics.

The universe controls us. We do not control the universe.

This brings me to the Gene Wolfe quote mentioned at the beginning of this post:

This is what mankind has always wanted. … That the environment should respond to human thought. That is the core of magic and the oldest dream of mankind…. when humankind has dreamed of magic, the wish behind the dream has been the omnipotence of thought.

[to be continued]

Providence

10/30/11 04:49 PM

I had a prescription for new eyeglasses sitting on my desk for the last seven months. I had been procrastinating getting new glasses because I didn't particularly like my optometrist after a new crew took over, but inertia held me back from trying another establishment. On Friday, 10/21, I finally decided to try Modern Eyes. My daughter had gotten her glasses there and was satisfied. It was late in the day so, after placing my order, I walked next door to Bonefish for a relaxing beverage. Just as I was about to place my drink order, my phone rang. It was the optometrist asking for my prescription numbers, which I had forgotten to leave with him. Walked back, dropped it off, and went back to Bonefish. Had I not stopped for a drink, I would have been halfway home when the optometrist called.

On Saturday, Becky and I went to the Southeastern Animal Fiber Fair, in Fletcher, NC. The event is held in a large indoor arena. To our surprise, we ran into a friend we hadn't seen in 20 or more years. J, and her husband W, attended the same church Becky and I went to after we moved to Georgia 31 years ago. J and W moved to the Greenville area 4 years ago. It was wonderful seeing her again and catching up on mutual friends.

On Saturday, Becky and I went to the Southeastern Animal Fiber Fair, in Fletcher, NC. The event is held in a large indoor arena. To our surprise, we ran into a friend we hadn't seen in 20 or more years. J, and her husband W, attended the same church Becky and I went to after we moved to Georgia 31 years ago. J and W moved to the Greenville area 4 years ago. It was wonderful seeing her again and catching up on mutual friends.

Atheism and Evidence, Redux

08/12/11 11:43 PM

In May I wrote "Atheism: It isn't about evidence". The gist was that the evidence for/against theism in general, and Christianity in particular, is the same for both theist and atheist. The difference is how brains process that evidence. I cited this article that said that people with Asperger's typically don't think teleologically. It also said that atheists think teleologically, but then suppress those thoughts.

Today, I came across the article "Does Secularism Make People More Ethical?" The main thesis of the article is nonsense, but it does reference work by Catherine Caldwell-Harris of Boston University. Der Spiegel (The Mirror) said:

Boston University's Catherine Caldwell-Harris is researching the differences between the secular and religious minds. "Humans have two cognitive styles," the psychologist says. "One type finds deeper meaning in everything; even bad weather can be framed as fate. The other type is neurologically predisposed to be skeptical, and they don't put much weight in beliefs and agency detection."

Caldwell-Harris is currently testing her hypothesis through simple experiments. Test subjects watch a film in which triangles move about. One group experiences the film as a humanized drama, in which the larger triangles are attacking the smaller ones. The other group describes the scene mechanically, simply stating the manner in which the geometric shapes are moving. Those who do not anthropomorphize the triangles, she suspects, are unlikely to ascribe much importance to beliefs. "There have always been two cognitive comfort zones," she says, "but skeptics used to keep quiet in order to stay out of trouble."

This broadly agrees with the Scientific American article, although it isn't clear if the non-anthropomorphizing group is thinking teleologically, but then suppressing it (which is characteristic of atheists) or not seeing meaning at all (characteristic of those with Asperger's).

Caldwell-Harris' work buttresses the thesis of Atheism: It isn't about evidence.

Too, her work is interesting from a perspective in artificial intelligence. One purpose of the Turing Test is to determine whether or not an artificial intelligence has achieved human-level capability. Her "triangle film" isn't dissimilar from a form of Turing Test since agency detection is a component of recognizing intelligence. If the movement of the triangles was truly random, then the non-anthropomorphizing group was correct in giving a mechanical interpretation to the scene. But if the filmmaker imbued the triangle film with meaning, then the anthropomorphizing group picked up a sign of intelligent agency which was missed by the other group.

I wrote her and asked about this. She has absolutely no reason to respond to my query, but I hope she will.

Finally, I have to mention that the Der Spiegel article cites researchers that claim that secularism will become the majority view in the west, which contradicts the sources in my blog post. On the one hand, it's a critical component of my argument. On the other hand, I just don't have time for more research into this right now.

Today, I came across the article "Does Secularism Make People More Ethical?" The main thesis of the article is nonsense, but it does reference work by Catherine Caldwell-Harris of Boston University. Der Spiegel (The Mirror) said:

Boston University's Catherine Caldwell-Harris is researching the differences between the secular and religious minds. "Humans have two cognitive styles," the psychologist says. "One type finds deeper meaning in everything; even bad weather can be framed as fate. The other type is neurologically predisposed to be skeptical, and they don't put much weight in beliefs and agency detection."

Caldwell-Harris is currently testing her hypothesis through simple experiments. Test subjects watch a film in which triangles move about. One group experiences the film as a humanized drama, in which the larger triangles are attacking the smaller ones. The other group describes the scene mechanically, simply stating the manner in which the geometric shapes are moving. Those who do not anthropomorphize the triangles, she suspects, are unlikely to ascribe much importance to beliefs. "There have always been two cognitive comfort zones," she says, "but skeptics used to keep quiet in order to stay out of trouble."

This broadly agrees with the Scientific American article, although it isn't clear if the non-anthropomorphizing group is thinking teleologically, but then suppressing it (which is characteristic of atheists) or not seeing meaning at all (characteristic of those with Asperger's).

Caldwell-Harris' work buttresses the thesis of Atheism: It isn't about evidence.

Too, her work is interesting from a perspective in artificial intelligence. One purpose of the Turing Test is to determine whether or not an artificial intelligence has achieved human-level capability. Her "triangle film" isn't dissimilar from a form of Turing Test since agency detection is a component of recognizing intelligence. If the movement of the triangles was truly random, then the non-anthropomorphizing group was correct in giving a mechanical interpretation to the scene. But if the filmmaker imbued the triangle film with meaning, then the anthropomorphizing group picked up a sign of intelligent agency which was missed by the other group.

I wrote her and asked about this. She has absolutely no reason to respond to my query, but I hope she will.

Finally, I have to mention that the Der Spiegel article cites researchers that claim that secularism will become the majority view in the west, which contradicts the sources in my blog post. On the one hand, it's a critical component of my argument. On the other hand, I just don't have time for more research into this right now.

Response to James

07/31/11 08:38 PM

James commented on my post Bad Arguments Against Materialism a month ago and it deserves a response. I appreciate every reader and, while I may not respond to every comment, I do want to engage in dialog. "Many eyes make short work of bugs" can be as true here as it can be with software (but don't get me started on "code reviews" that miss even the simplest mistakes!)

Under materialism, the coder is the universe itself. That is, the motion of the particles, operating under physical law, gave rise to the motion of electrons in certain patterns that make up our thoughts. Whether or not this is the true explanation is hotly contested. One side will argue that this is such an improbable occurrence that it couldn't be the right explanation. The other side will argue that improbable things happen. Both sides tailor their argument according to their preconceived notions about the nature of reality. Synchronously, John C. Wright has a droll take on it here.

This is a topic that I hope to get to this year. There is an explanation for this, see Axelrod's "The Evolution of Cooperation." For an idea of how the argument will go, see Cybertheology.

First, whether or not a goal is good depends on its relationship to other goals, and those goals exist in relationship to other goals, and so on. That's one reason why morality is such a difficult subject -- the size of the goal space is so large. It's much, much bigger than the complex games of Chess and Go.

Second, there may be times when it's necessary for one group to die so that another may live. We don't like that notion, because we may think that the reasoning that leads to the deaths of others could one day be used against us; on the other hand, listen to the reasons given for the necessity of using nuclear weapons against Japan in World War II. That there is no universal agreement on this shows how difficult a problem it is.

It has happened, and Axelrod (with William D. Hamilton) gives examples of this in chapter 5: The Evolution of Cooperation in Biological Systems.

Then you're a better man than St. Paul, who wrote:

Actually, it does. Again, St. Paul wrote, "I do not nullify the grace of God; for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing." (Gal 2:21) and "For if a law had been given that could make alive, then righteousness would indeed come through the law." (Gal 3:21).

My only comment - and I'll leave it at this - is that, despite a very well worded argument, you seem to forget the very basis on which your argument stands. That being, using your own abstract allusion, though information (of any type, not just software of course) can be coded in zeros and ones, does not record itself. There needs be a CODER.

Under materialism, the coder is the universe itself. That is, the motion of the particles, operating under physical law, gave rise to the motion of electrons in certain patterns that make up our thoughts. Whether or not this is the true explanation is hotly contested. One side will argue that this is such an improbable occurrence that it couldn't be the right explanation. The other side will argue that improbable things happen. Both sides tailor their argument according to their preconceived notions about the nature of reality. Synchronously, John C. Wright has a droll take on it here.

It may be transmitted one way or another, either zeros and ones, or brain waves, or goal-seeking algorithms, but itself is something rather more transcendent. If you doubt that, then why would more than one person get upset over the same wrong? (Say invasion of a country you don't even live in) or be offended when you step on the foot of an elderly woman whom you don't even know?

This is a topic that I hope to get to this year. There is an explanation for this, see Axelrod's "The Evolution of Cooperation." For an idea of how the argument will go, see Cybertheology.

And if we "call steps leading toward a goal good" then that simply means any goal is good. Including, say, a despot's systematic murder of an entire people. There are few goals as effective as that for survival of a people, state or regime.

First, whether or not a goal is good depends on its relationship to other goals, and those goals exist in relationship to other goals, and so on. That's one reason why morality is such a difficult subject -- the size of the goal space is so large. It's much, much bigger than the complex games of Chess and Go.

Second, there may be times when it's necessary for one group to die so that another may live. We don't like that notion, because we may think that the reasoning that leads to the deaths of others could one day be used against us; on the other hand, listen to the reasons given for the necessity of using nuclear weapons against Japan in World War II. That there is no universal agreement on this shows how difficult a problem it is.

You also note that Axelrod's game theory shows how the golden rule can arise in biological systems. Well, if that happens so "naturally," why hasn't it happened in any of the (numerous beyond count) organisms that have, on an evolutionary scale, been here longer than Man? Say, for instance, the shark? Or the ant, which has a complicated social system?

It has happened, and Axelrod (with William D. Hamilton) gives examples of this in chapter 5: The Evolution of Cooperation in Biological Systems.

We are not necessarily walking conundrums, BTW. …

Then you're a better man than St. Paul, who wrote:

I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate. Now if I do what I do not want, I agree that the law is good. But in fact it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwells within me. For I know that nothing good dwells within me, that is, in my flesh. I can will what is right, but I cannot do it. For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I that do it, but sin that dwells within me. So I find it to be a law that when I want to do what is good, evil lies close at hand. For I delight in the law of God in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind, making me captive to the law of sin that dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will rescue me from this body of death? [Rom 7:15-24]

Which leads me to the last point: No, the Bible doesn't teach that Jesus died because of man's inability to follow any external code.

Actually, it does. Again, St. Paul wrote, "I do not nullify the grace of God; for if justification comes through the law, then Christ died for nothing." (Gal 2:21) and "For if a law had been given that could make alive, then righteousness would indeed come through the law." (Gal 3:21).

Bad Arguments Against Materialism

04/16/11 03:00 PM

Lately I have read, or participated in, several arguments against materialism: John C. Wright in Dialog With An Adding Machine and Taking Ideas Seriously, Job's Goat and Babelfish, and Rusty Lopez and Morality: a stowaway, onboard for the entire journey. In Taking Ideas Seriously I found myself arguing against Wright's objections to materialism, and arguing against another reader's arguments for materialism. That is, I find the typical theistic arguments against materialism to be flawed yet I find the typical atheistic arguments for materialism equally flawed.

I want to examine and expose bad theistic arguments against materialism, which generally reduce to the idea that materialism cannot explain abstract thought in general and morality in particular.

As a software engineer, I know that software -- which is abstract thought -- can be encoded in material: zero's and ones flowing through NAND gates arranged in certain ways. Wire up NAND gates one way and you have a circuit that adds (e.g. here). Wire them up another way and you have a circuit that can subtract. Wire them up yet another way and you have memory. A more complicated arrangement could recognize whether or not a given circuit is an adder (i.e. one implements "this adds," the other implements "that is an adder"). If something can be expressed as software, it can be expressed as hardware. The relationships between the basic parts, whether they are NAND gates, NOR gates, or something else, and the movement of electrons (or photons), between them encode the abstract thought. Yet Lopez wrote:

That thought can be encoded in hardware should be familiar to Christians. After all, the Word became Flesh. Where the theist and materialist differ is in the initial conditions. The materialist will say that matter is made of atoms, and atoms are made of protons, neutrons, and electrons; and protons and neutrons are made of up quarks. One overview of the "particle zoo" is here. String theory offers the idea that below the currently known elementary particles lie even smaller one dimensional oscillating lines. Do strings really exist? We don't know. What we do know is that simple things combine to make more complex things, more complex things combine to make even more complex things. The greater the number of connections between things, the greater the complexity. Perhaps this is why the human mind tries to reduce things to their most simple components and this is what drives the search for strings in one discipline and God in another. Whether it is clearly revealed in Scripture or not, there has certainly been the idea that God is immaterial, irreducible, and simple. The materialist will say that at the bottom lies matter and the ways they combine. This combining, recombining, and recombining again eventually resulted in self-aware humans. Genetic algorithms, after all, do work. The theist says that at the bottom lies an immaterial self-aware Person who created matter and, eventually, self-aware people. In one camp, self-awareness is emergent; in another it is fundamental. After all, when Moses asked God to reveal His name, He said, "I am who I am."

If the existence of self-aware thought is one way theists argue against materialism, likewise is the existence of morality which theists claim cannot be explained by science. Lopez also wrote:

If morality is a property of the goal-seeking behavior of self-aware beings, and the goal is reproductive success, then certain strategies will be more effective than others. Axelrod used game theory to show how something like the golden rule can arise in biological systems. There is one sense in which the "game" of life is like the game of chess -- both have state spaces so large that it is impossible to fully analyze all strategies. Life, like chess, requires us to develop heuristics for winning the game. It's a field that's wide open for research via computer simulation. But even if we can say with confidence which choices ought to be made, this leads to the next issue.

I am puzzled the theist's insistence on the existence of and necessity for an objective morality: something written in stone which solves the "is-ought" problem, to which all mankind (and extraterrestrial life, if it exists) must agree "this ought to be," i.e. "these are the goals toward which all must strive, whether freely or not." The materialist isn't bothered by moral relativism any more than he is bothered by the fact that there are different languages. It's the way our brains work. The goal-seeking algorithm in our brain tends to reject fixed goals. We are walking conundrums that want to choose yet aren't satisfied by the choices we make. John McCarthy recognized this in Programs with Common Sense, Axelrod found it via computer simulation in The Evolution of Cooperation, Hume exposed the problem, but not the cause; St. Paul made it the basis of his exposition of the Gospel in the book of Romans and drove the point home in his letter to the Galatians, and it's central to the story of the creation of man in Genesis (see What Really Happened in Eden). After all, the central claim of Christianity is that Jesus died and rose from the dead because of man's inability to follow any external moral code. To say that the need for an objective external standard is an argument against materialism completely misses the point of Christianity. We know that our brains are wired for teleological thinking; people with Asperger's have been shown to be deficient in this area (People with Asperger's less likely to see purpose behind the events in their lives). The theist says that God represents the ultimate goal, the ultimate purpose, the solution to the is-ought problem; the materialist will say that this is just something that minds with our properties wished they had. It's how scientists say we're wired, its how Christianity says we're wired. Arguing that materialism can't support an objective moral standard won't change that wiring.

In summary, then, neither abstract thought nor morality are a problem for a materialist, as currently argued by theists.

I want to examine and expose bad theistic arguments against materialism, which generally reduce to the idea that materialism cannot explain abstract thought in general and morality in particular.

As a software engineer, I know that software -- which is abstract thought -- can be encoded in material: zero's and ones flowing through NAND gates arranged in certain ways. Wire up NAND gates one way and you have a circuit that adds (e.g. here). Wire them up another way and you have a circuit that can subtract. Wire them up yet another way and you have memory. A more complicated arrangement could recognize whether or not a given circuit is an adder (i.e. one implements "this adds," the other implements "that is an adder"). If something can be expressed as software, it can be expressed as hardware. The relationships between the basic parts, whether they are NAND gates, NOR gates, or something else, and the movement of electrons (or photons), between them encode the abstract thought. Yet Lopez wrote:

For this to be true, those thoughts have to exist independently of the hardware which is our minds. They have to exist in the mind of God. But he hasn't shown that this is the case nor do I know how to prove it, even though I think it true ["in Him we live and move and have our being." -- Acts 17:28]. Just as the materialist cannot prove his position that the thoughts cease when the electrons stop moving (see my post Materialism, Theism, and Information where I have this argument with a materialist), the theist also hasn't made their case. It's one thing to cite Scripture, it's quite another to show why it must be so independently of special revelation.For example, while electrical impulses may occur when a person has particluar [sic] thoughts or feelings (or propositional qualities, per Greg Koukl), the impulses themselves are not the thoughts or feelings.

That thought can be encoded in hardware should be familiar to Christians. After all, the Word became Flesh. Where the theist and materialist differ is in the initial conditions. The materialist will say that matter is made of atoms, and atoms are made of protons, neutrons, and electrons; and protons and neutrons are made of up quarks. One overview of the "particle zoo" is here. String theory offers the idea that below the currently known elementary particles lie even smaller one dimensional oscillating lines. Do strings really exist? We don't know. What we do know is that simple things combine to make more complex things, more complex things combine to make even more complex things. The greater the number of connections between things, the greater the complexity. Perhaps this is why the human mind tries to reduce things to their most simple components and this is what drives the search for strings in one discipline and God in another. Whether it is clearly revealed in Scripture or not, there has certainly been the idea that God is immaterial, irreducible, and simple. The materialist will say that at the bottom lies matter and the ways they combine. This combining, recombining, and recombining again eventually resulted in self-aware humans. Genetic algorithms, after all, do work. The theist says that at the bottom lies an immaterial self-aware Person who created matter and, eventually, self-aware people. In one camp, self-awareness is emergent; in another it is fundamental. After all, when Moses asked God to reveal His name, He said, "I am who I am."

If the existence of self-aware thought is one way theists argue against materialism, likewise is the existence of morality which theists claim cannot be explained by science. Lopez also wrote:

The materialist answer is fairly simple. Morality is what we call the goal-seeking algorithm(s) in our brain (see my article The Mechanism of Morality). Basically, we call steps leading toward a goal good, and steps leading away bad. Robert Axelrod, in his ground-breaking book The Evolution of Cooperation, showed how strategies such as cooperation, forgiveness, and non-covetousness could arise between competing selfish agents. Morality is then objective the way language is objective. If language is the means whereby a community uses arbitrary symbols to share meaning, morality is the means whereby a community shares goals. The grounding for the imposition of one moral system over another would then be whether or not it leads to greater reproductive success, in exactly the same way that English is currently the lingua franca of science, technology, and business.Indeed, if our entire essence - the totality of who we are, was reducible solely to particles in motion, then what justification would there be for any concept of an objective morality? What grounding** would there be for any application - or imposition - of morality from one human being to another? Survival of the fittest? Perpetuation of our species? The selfish gene?

If morality is a property of the goal-seeking behavior of self-aware beings, and the goal is reproductive success, then certain strategies will be more effective than others. Axelrod used game theory to show how something like the golden rule can arise in biological systems. There is one sense in which the "game" of life is like the game of chess -- both have state spaces so large that it is impossible to fully analyze all strategies. Life, like chess, requires us to develop heuristics for winning the game. It's a field that's wide open for research via computer simulation. But even if we can say with confidence which choices ought to be made, this leads to the next issue.

I am puzzled the theist's insistence on the existence of and necessity for an objective morality: something written in stone which solves the "is-ought" problem, to which all mankind (and extraterrestrial life, if it exists) must agree "this ought to be," i.e. "these are the goals toward which all must strive, whether freely or not." The materialist isn't bothered by moral relativism any more than he is bothered by the fact that there are different languages. It's the way our brains work. The goal-seeking algorithm in our brain tends to reject fixed goals. We are walking conundrums that want to choose yet aren't satisfied by the choices we make. John McCarthy recognized this in Programs with Common Sense, Axelrod found it via computer simulation in The Evolution of Cooperation, Hume exposed the problem, but not the cause; St. Paul made it the basis of his exposition of the Gospel in the book of Romans and drove the point home in his letter to the Galatians, and it's central to the story of the creation of man in Genesis (see What Really Happened in Eden). After all, the central claim of Christianity is that Jesus died and rose from the dead because of man's inability to follow any external moral code. To say that the need for an objective external standard is an argument against materialism completely misses the point of Christianity. We know that our brains are wired for teleological thinking; people with Asperger's have been shown to be deficient in this area (People with Asperger's less likely to see purpose behind the events in their lives). The theist says that God represents the ultimate goal, the ultimate purpose, the solution to the is-ought problem; the materialist will say that this is just something that minds with our properties wished they had. It's how scientists say we're wired, its how Christianity says we're wired. Arguing that materialism can't support an objective moral standard won't change that wiring.

In summary, then, neither abstract thought nor morality are a problem for a materialist, as currently argued by theists.

Everything is a remix

02/02/11 10:29 AM

Earlier this morning I uploaded “Christian Doctrine, Ancient Egypt, Game Theory”. Also today Daring Fireball posted a link to the very interesting site, Everything Is A Remix. Of course, “everything is a remix” is a remix of “there is nothing new under the sun.” (Ecclesiastes 1:9) But, as I noted in Christian Doctrine, Ancient Egypt, Game Theory, Christianity’s golden rule and the admonition to not return evil for good are found in Egyptian culture long before Christ.

Do take a few minutes to watch the two (of four) videos at Everything Is A Remix.

Do take a few minutes to watch the two (of four) videos at Everything Is A Remix.

Static Code Analysis

06/17/10 09:57 AM

[updated 1.6.2024 to fix the nodes in the C code]

This post will tie together problem representation, the power of Lisp, and the fortuitous application of the solution of an AI exercise to a real world problem in software engineering.

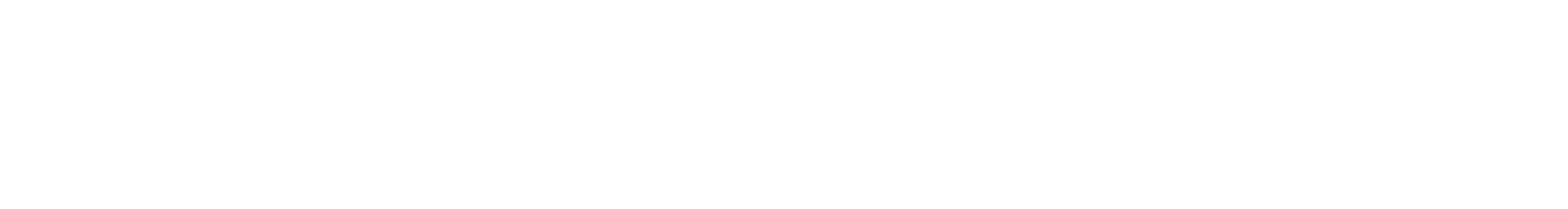

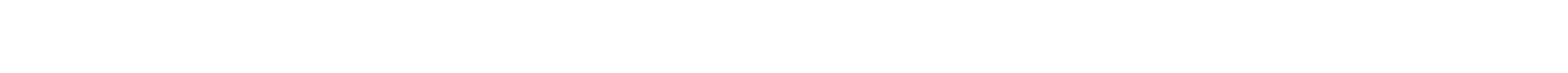

Problem 3-4b in Introduction to Artificial Intelligence is to find a path from Start to Finish that goes though each node only once. The graph was reproduced using OmniGraffle. Node t was renamed to node v for a reason which will be explained later.

The immediate inclination might be to throw some code at the problem. How should the graph be represented? Thinking in one programming language might lead to creating a node structure that contained links to other nodes. A first cut in C might look something like this:

#define MAX_CONNECTIONS 6

typedef struct node

{

char *name;

struct node *next[MAX_CONNECTIONS];

} NODE;

extern NODE start, a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k;

extern NODE l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, u, v, finish;

NODE start = {"start", {&a, &f, &l, &k, &s, NULL}};

NODE a = {"a", {&d, &h, &b, &f, NULL, NULL}};

NODE b = {"b", {&g, &m, &l, &a, NULL,NULL}};

...

Then we'd have to consider how to construct the path and whether path-walk information should be kept in a node or external to it.

If we're lucky, before we get too far into writing the code, we'll notice that there is only one way into q. Since there's only one way in, visiting q means that u will be visited twice. So the problem has no solution. It's likely the intent of the problem was to stimulate thinking about problem description, problem representation, methods for mapping the "human" view of the problem into a representation suitable for a machine, and strategies for finding relationships between objects and reasoning about them.

On the other hand, maybe the graph is in error. After all, the very first paragraph of my college calculus textbook displayed a number line where 1.6 lay between 0 and 1. Suppose that q is also connected to v, p, m, and n. Is there a solution?

Using C for this is just too painful. I want to get an answer without having to first erect scaffolding. Lisp is a much better choice. The nodes can be represented directly:

(defparameter start '(a f l k s))

(defparameter a '(f b h d))

(defparameter b '(a l m g))

(defparameter c '(d o i g))

...

The code maps directly to the problem. Minor liberties were taken. Nodes, such as a, don't point back to start since the solution never visits the same node twice. Node t was renamed v, since t is a reserved symbol. The code is then trivial to write. It isn't meant to be pretty (the search termination test is particularly egregious), particularly efficient, or a general breadth-first search function with all the proper abstractions. Twenty-three lines of code to represent the problem and twelve lines to solve it.

One solution is (START K E S V U Q P M B L F A H G C D J O R I N FINISH).

The complete set of solutions for the revised problem is:

(START K E S V U Q P M B L F A H G C D J O R I N FINISH)

(START K E S V U Q P M B L F A H D J O R I C G N FINISH)

(START K E S V U Q P L F A H D J O R I C G B M N FINISH)

(START K E P M B L F A H G C D J O R I N U Q V S FINISH)

(START K E P M B L F A H D J O R I C G N U Q V S FINISH)

(START K E P L F A H D J O R I C G B M N U Q V S FINISH)

This exercise turned out to have direct application to a real world problem. Suppose threaded systems S1 and S2 have module M that uses non-nesting binary semaphores to protect accesses to shared resources. Furthermore, these semaphores have the characteristic that they can time out if the semaphore isn't acquired after a specified period. Eventually, changes to S1 lead to changing the semaphores in M to include nesting. So there were two systems, S1 with Mn and S2 with M. Later, both systems started exhibiting sluggishness in servicing requests. One rare clue to the problem was that semaphores in Mn were timing out. No such clue was available for M because M did not provide that particular bit of diagnostic information. On the other hand, the problem seemed to exhibit itself more frequently with M than Mn. One problem? Two? More?

Semaphores in M and Mn could be timing out because of priority inversion. Or maybe there was a rare code path in M where a thread tried to acquire a semaphore more than once. That would explain the prevalence of the problem in S2 but would not explain the problem in S1.

This leads to at least two questions:

(defparameter func_1 '(func_2 acquire sem_1 acquire sem_2

func_10 func_4 release sem_2 release sem_1))

A function that requires a semaphore be held could be described by:

(defparameter func_4 '(demand sem_2))

The description of a benign function:

(defparameter func_7 '())

It's then easy to write code which walks these descriptions looking for pathological conditions. Absent a C/C++ to Lisp translator, the tedious part is creating the descriptions. But this is at least aided by the pathwalker complaining if a function definition isn't found and is far less error prone than manual examination of the code paths. Would I have used this method to analyze the code if I hadn't just done the AI problem? I hope so, but sometimes the obvious isn't.

After completing the descriptions for S1, the addition of one function call to an existing function in M was the basis for changing the semaphores so that they nested. The descriptions for S2 are not yet complete.

This post will tie together problem representation, the power of Lisp, and the fortuitous application of the solution of an AI exercise to a real world problem in software engineering.

Problem 3-4b in Introduction to Artificial Intelligence is to find a path from Start to Finish that goes though each node only once. The graph was reproduced using OmniGraffle. Node t was renamed to node v for a reason which will be explained later.

The immediate inclination might be to throw some code at the problem. How should the graph be represented? Thinking in one programming language might lead to creating a node structure that contained links to other nodes. A first cut in C might look something like this:

#define MAX_CONNECTIONS 6

typedef struct node

{

char *name;

struct node *next[MAX_CONNECTIONS];

} NODE;

extern NODE start, a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h, i, j, k;

extern NODE l, m, n, o, p, q, r, s, u, v, finish;

NODE start = {"start", {&a, &f, &l, &k, &s, NULL}};

NODE a = {"a", {&d, &h, &b, &f, NULL, NULL}};

NODE b = {"b", {&g, &m, &l, &a, NULL,NULL}};

...

Then we'd have to consider how to construct the path and whether path-walk information should be kept in a node or external to it.

If we're lucky, before we get too far into writing the code, we'll notice that there is only one way into q. Since there's only one way in, visiting q means that u will be visited twice. So the problem has no solution. It's likely the intent of the problem was to stimulate thinking about problem description, problem representation, methods for mapping the "human" view of the problem into a representation suitable for a machine, and strategies for finding relationships between objects and reasoning about them.

On the other hand, maybe the graph is in error. After all, the very first paragraph of my college calculus textbook displayed a number line where 1.6 lay between 0 and 1. Suppose that q is also connected to v, p, m, and n. Is there a solution?

Using C for this is just too painful. I want to get an answer without having to first erect scaffolding. Lisp is a much better choice. The nodes can be represented directly:

(defparameter start '(a f l k s))

(defparameter a '(f b h d))

(defparameter b '(a l m g))

(defparameter c '(d o i g))

...

The code maps directly to the problem. Minor liberties were taken. Nodes, such as a, don't point back to start since the solution never visits the same node twice. Node t was renamed v, since t is a reserved symbol. The code is then trivial to write. It isn't meant to be pretty (the search termination test is particularly egregious), particularly efficient, or a general breadth-first search function with all the proper abstractions. Twenty-three lines of code to represent the problem and twelve lines to solve it.

One solution is (START K E S V U Q P M B L F A H G C D J O R I N FINISH).

The complete set of solutions for the revised problem is:

(START K E S V U Q P M B L F A H G C D J O R I N FINISH)

(START K E S V U Q P M B L F A H D J O R I C G N FINISH)

(START K E S V U Q P L F A H D J O R I C G B M N FINISH)

(START K E P M B L F A H G C D J O R I N U Q V S FINISH)

(START K E P M B L F A H D J O R I C G N U Q V S FINISH)

(START K E P L F A H D J O R I C G B M N U Q V S FINISH)

This exercise turned out to have direct application to a real world problem. Suppose threaded systems S1 and S2 have module M that uses non-nesting binary semaphores to protect accesses to shared resources. Furthermore, these semaphores have the characteristic that they can time out if the semaphore isn't acquired after a specified period. Eventually, changes to S1 lead to changing the semaphores in M to include nesting. So there were two systems, S1 with Mn and S2 with M. Later, both systems started exhibiting sluggishness in servicing requests. One rare clue to the problem was that semaphores in Mn were timing out. No such clue was available for M because M did not provide that particular bit of diagnostic information. On the other hand, the problem seemed to exhibit itself more frequently with M than Mn. One problem? Two? More?

Semaphores in M and Mn could be timing out because of priority inversion. Or maybe there was a rare code path in M where a thread tried to acquire a semaphore more than once. That would explain the prevalence of the problem in S2 but would not explain the problem in S1.

This leads to at least two questions:

- What change in S1 necessitated adding support for nesting to the semaphores in Mn?

- Is there a code path in M where a semaphore tries to nest?

(defparameter func_1 '(func_2 acquire sem_1 acquire sem_2

func_10 func_4 release sem_2 release sem_1))

A function that requires a semaphore be held could be described by:

(defparameter func_4 '(demand sem_2))

The description of a benign function:

(defparameter func_7 '())

It's then easy to write code which walks these descriptions looking for pathological conditions. Absent a C/C++ to Lisp translator, the tedious part is creating the descriptions. But this is at least aided by the pathwalker complaining if a function definition isn't found and is far less error prone than manual examination of the code paths. Would I have used this method to analyze the code if I hadn't just done the AI problem? I hope so, but sometimes the obvious isn't.

After completing the descriptions for S1, the addition of one function call to an existing function in M was the basis for changing the semaphores so that they nested. The descriptions for S2 are not yet complete.

La Belle Heaulmiere

11/07/09 08:46 PM

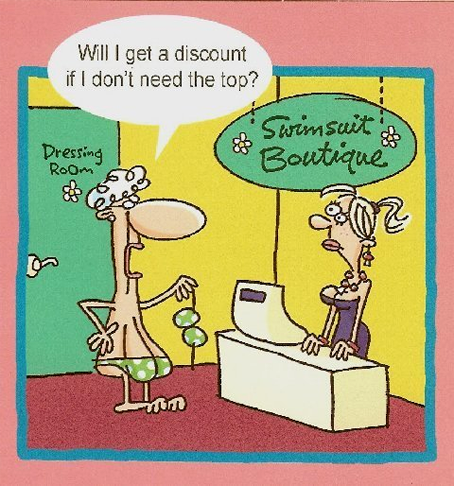

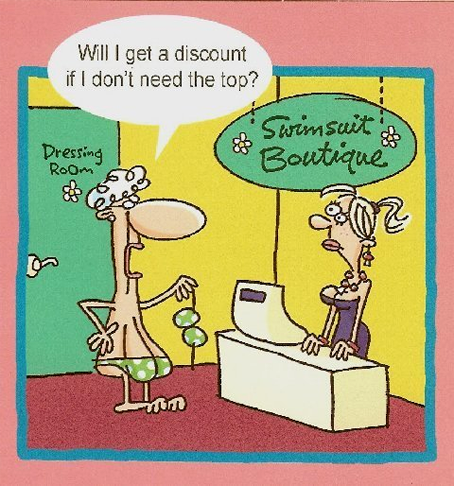

My wife sent me this cartoon with the comment, "This may be me in the not-to-distant future."

At the same time, I was re-reading Heinlein's Stranger In A Strange Land (yes, the 1975 Berkeley edition. My hardback copy of the uncut version is on loan) and came across Jubal's description of Rodin's "La Belle Heaulmière":