Bad Arguments

Searle's Chinese Room: Another Nail

02/17/24 08:06 PM

[updated 2/28/2024 - See "Addendum"]

[updated 3/9/2024 - note on Searle's statement that "programs are not machines"]

I have discussed Searle's "Chinese Room Argument" twice before: here and here. It isn't necessary to review them. While both of them argue against Searle's conclusion, they aren't as complete as I think they could be. This is one more attempt to put another nail in the coffin, but the appeal of Searle's argument is so strong - even though it is manifestly wrong - that it may refuse to stay buried. The Addendum explains why.

Searle's paper, "Mind, Brains, and Programs" is here. He argues that computers will never be able to understand language the way humans do for these reasons:

To understand why 2 is only partially true, we have to understand why 3 is false.

I was able to correct my behavior by establishing new associations: temperature and libido with German usage of "heiss". That associative behavior can be communicated to a machine. A machine, sensing a rise in temperature, could then inform an operator of its distress, "Es ist mir heiss!". Likely (at least, for now) lacking libido, it would not say, "Ich bin heiss."

Having shown that Searle's argument is based on a complete misunderstanding of computation, I wish to address selected statements in his paper.

Read More...

[updated 3/9/2024 - note on Searle's statement that "programs are not machines"]

I have discussed Searle's "Chinese Room Argument" twice before: here and here. It isn't necessary to review them. While both of them argue against Searle's conclusion, they aren't as complete as I think they could be. This is one more attempt to put another nail in the coffin, but the appeal of Searle's argument is so strong - even though it is manifestly wrong - that it may refuse to stay buried. The Addendum explains why.

Searle's paper, "Mind, Brains, and Programs" is here. He argues that computers will never be able to understand language the way humans do for these reasons:

- Computers manipulate symbols.

- Symbol manipulation is insufficient for understanding the meaning behind the symbols being manipulated.

- Humans cannot communicate semantics via programming.

- Therefore, computers cannot understand symbols the way humans understand symbols.

- Is certainly true. But Searle's argument ultimately fails because he only considers a subset of the kinds of symbol manipulation a computer (and a human brain) can do.

- Is partially true. This idea is also expressed as "syntax is insufficient for semantics." I remember, from over 50 years ago, when I started taking German in 10th grade. We quickly learned to say "good morning, how are you?" and to respond with "I'm fine. And you?" One morning, our teacher was standing outside the classroom door and asked each student as they entered, the German equivalent of "Good morning," followed by the student's name, "how are you?" Instead of answering from the dialog we had learned, I decided to ad lib, "Ice bin heiss." My teacher turned bright red from the neck up. Bless her heart, she took me aside and said, "No, Wilhem. What you should have said was, 'Es ist mir heiss'. To me it is hot. What you said was that you are experiencing increased libido." I had used a simple symbol substitution, "Ich" for "I", "bin" for "am", and "heiss" for "hot", temperature-wise. But, clearly, I didn't understand what I was saying. Right syntax, wrong semantics. Nevertheless, I do now understand the difference. What Searle fails to establish is how meaningless symbols acquire meaning. So he handicaps the computer. The human has meaning and substitution rules; Searle only allows the computer substitution rules.

- Is completely false.

To understand why 2 is only partially true, we have to understand why 3 is false.

- A Turing-complete machine can simulate any other Turing machine. Two machines are Turing equivalent if each machine can simulate the other.

- The lambda calculus is Turing complete.

- A machine composed of NAND gates (a "computer" in the everyday sense) can be Turing complete.

- A NAND gate (along with a NOR gate) is a "universal" logic gate.

- Memory can also be constructed from NAND gates.

- The equivalence of a NAND-based machine and the lambda calculus is demonstrated by instantiating the lambda calculus on a computer.1

- From 3, every computer program can be written as expressions in the lambda calculus; every computer program can be expressed as an arrangement of logic gates. We could, if we so desired, build a custom physical device for every computer program. But it is massively economically unfeasible to do so.

- Because every computer program has an equivalent arrangement of NAND gates2, a Turing-complete machine can simulate that program.

- NAND gates are building-blocks of behavior. So the syntax of every computer program represents behavior.

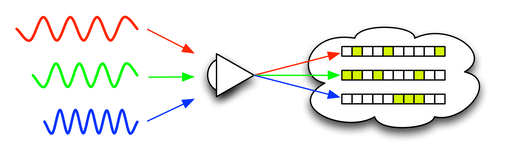

- Having established that computer programs communicate behavior, we can easily see what Searle's #2 is only partially true. Symbol substitution is one form of behavior. Semantics is another. Semantics is "this is that" behavior. This is the basic idea behind a dictionary. The brain associates visual, aural, temporal, and other sensory input and this is how we acquire meaning. Associating the visual input of a "dog", the sound "dog", the printed word "dog", the feel of a dog's fur, are how we learn what "dog" means. We have massive amounts of data that our brain associates to build meaning. We handicap our machines, first, by not typically giving them the ability to have the same experiences we do. We handicap them, second, by not giving them the vast range of associations that we have. Nevertheless, there are machines that demonstrate that they understand colors, shapes, locations, and words. When told to describe a scene, they can. When requested to "take the red block on the table and place it in the blue bowl on the floor", they can.

I was able to correct my behavior by establishing new associations: temperature and libido with German usage of "heiss". That associative behavior can be communicated to a machine. A machine, sensing a rise in temperature, could then inform an operator of its distress, "Es ist mir heiss!". Likely (at least, for now) lacking libido, it would not say, "Ich bin heiss."

Having shown that Searle's argument is based on a complete misunderstanding of computation, I wish to address selected statements in his paper.

Read More...

Comments

Critiquing Calvinism

01/06/23 01:20 PM

... the Remonstrants were concerned about the teaching that God forces his grace on sinners irresistibly. [emphasis mine]

...

Bending the will of a fallible being by an omnipotent Being powerfully and unfailingly is not merely sweet persuasion. It is forcing one to change one’s mind against one’s will.

...

God changing our will invincibly in irresistible grace brings to mind phenomena such as hypnotism or brainwashing.

...

Note the striking contradiction—God will “overcome all resistance and make his influence irresistible,” and yet “irresistible grace never implies that God forces us to believe against our will.” No attempt is made in the article to reconcile these apparently contradictory assertions.

I will try to reconcile these allegedly contradictory assertions. The idea that God forces the spiritually dead to awaken to life in Christ is common in Arminian arguments. But it simply isn't what God does. "Aha!" moments, "Eureka!" moments rise from the recesses of our minds and present to us a new way of seeing, a new way of thinking, and that new thing is so obvious that we wonder why we never encountered it before. Of course we embrace it. Why would we not? It has positively transformed a part of our life.

Lemke asks:

Why would there be a need to persuade someone who had already been regenerated by irresistible enabling grace?

God works through His word: written, oral, or otherwise. He gives sight to the blind and hearing to the deaf (Ex. 4:11). He gives transforming inspiration. Regeneration and persuasion go hand in hand. He regenerates through persuasion and persuades through regeneration.

I am reminded of the scene in "The Wizard of Oz" when Dorothy opens the door of her house and sees Oz in color. Before then, everything was in black and white. The external change of location which brought color into her life is a parallel to the internal change that brings new sight to the Christian. What Dorothy saw on the outside the Christian sees on the inside.

[1] The "marriage" argument. It is argued that Christ died for His bride, the Church, to "sanctify it, having cleansed it." [Eph 5:25-27].

There is an inseparable unity between Christ's death for the church and his sanctifying and cleansing it. Those from whom he died he also sanctifies and cleanses. Since the world is not sanctified and cleansed, then it is obvious that Christ did not die for it.

– Edwin H. Palmer, "The Five Points of Calvinism".

I don't think this argument survives Isaiah 54:5:

For your Maker is your husband, the Lord of hosts is his name; ...

– NRSV

Which makes 1 Cor 7:15 all the more interesting.

Quus, Redux

03/19/22 11:37 AM

[updated 3/20/2022 to add footnote 2]

Philip Goff explores Kripke's quss function, defined as:

Goff then claims:

This statement rests on some unstated assumptions. The calculator is a finite state machine. For simplicity, suppose the calculator has 10 digits, a function key (labelled "?" for mystery function) and "=" for result. There is a three character screen, so that any three digit numbers can be "quadded". The calculator can then produce 1000x1000 different results. A larger finite state machine can query the calculator for all one million possible inputs then collect and analyze the results. Given the definition of quss, the analyzer can then feed all one million possible inputs to quss, and show that the output of quss matches the output of the calculator.

Goff then tries to extend this result by making N larger than what the calculator can "handle". But this attempt fails, because if the calculator cannot handle bigN, then the conditionals (< a bigN) and (< b bigN) cannot be expressed, so the calculator can't implement quss on bigN. Since the function cannot even be implemented with bigN, it's pointless to ask what it's doing. Questions can only be asked about what the actual implementation is doing; not what an imagined unimplementable implementation is doing.

Goff then tries to apply this to brains and this is where the sleight of hand occurs. The supposed dichotomy between brains and calculators is that brains can know they are adding or quadding with numbers that are too big for the brain to handle. Therefore, brains are not calculators.

The sleight of hand is that our brains can work with the descriptions of the behavior, while most calculators are built with only the behavior. With calculators, and much software, the descriptions are stripped away so that only the behavior remains. But there exists software that works with descriptions to generate behavior. This technique is known as "symbolic computation". Programs such as Maxima, Mathematica, and Maple can know that they are adding or quadding because they can work from the symbolic description of the behavior. Like humans, they deal with short descriptions of large things1. We can't write out all of the digits in the number 10^120. But because we can manipulate short descriptions of big things, we can answer what quss would do if bigN were 10^80. 10^80 is less than 10^120, so quss would return 5. Symbolic computation would give the same answer. But if we tried to do that with the actual numbers, we couldn't. When the thing described doesn't fit, it can't be worked on. Or, if the attempt is made, the old programming adage, Garbage In - Garbage Out, applies to humans and machines alike.

[1] We deal with infinity via short descriptions, e.g. "10 goto 10". We don't actually try to evaluate this, because we know we would get stuck if we did. We tag it "don't evaluate". If we actually need a result with these kinds of objects, we get rid of the infinity by various finite techniques.

[2] This post title refers to a prior brief mention of quss here. In that post, it suggested looking at the wiring of a device to determine what it does. In this post, we look at the behavior of the device across all of its inputs to determine what it does. But we only do that because we don't embed a rich description of each behavior in most devices. If we did, we could simply ask the device what it is doing. Then, just as with people, we'd have to correlate their behavior with their description of their behavior to see if they are acting as advertised.

Philip Goff explores Kripke's quss function, defined as:

In English, if the two inputs are both less than 100, the inputs are added, otherwise the result is 5.

(defparameter N 100)

(defun quss (a b)

(if (and (< a N) (< b N))

(+ a b)

5))

Goff then claims:

Rather, it’s indeterminate whether it’s adding orquadding.

This statement rests on some unstated assumptions. The calculator is a finite state machine. For simplicity, suppose the calculator has 10 digits, a function key (labelled "?" for mystery function) and "=" for result. There is a three character screen, so that any three digit numbers can be "quadded". The calculator can then produce 1000x1000 different results. A larger finite state machine can query the calculator for all one million possible inputs then collect and analyze the results. Given the definition of quss, the analyzer can then feed all one million possible inputs to quss, and show that the output of quss matches the output of the calculator.

Goff then tries to extend this result by making N larger than what the calculator can "handle". But this attempt fails, because if the calculator cannot handle bigN, then the conditionals (< a bigN) and (< b bigN) cannot be expressed, so the calculator can't implement quss on bigN. Since the function cannot even be implemented with bigN, it's pointless to ask what it's doing. Questions can only be asked about what the actual implementation is doing; not what an imagined unimplementable implementation is doing.

Goff then tries to apply this to brains and this is where the sleight of hand occurs. The supposed dichotomy between brains and calculators is that brains can know they are adding or quadding with numbers that are too big for the brain to handle. Therefore, brains are not calculators.

The sleight of hand is that our brains can work with the descriptions of the behavior, while most calculators are built with only the behavior. With calculators, and much software, the descriptions are stripped away so that only the behavior remains. But there exists software that works with descriptions to generate behavior. This technique is known as "symbolic computation". Programs such as Maxima, Mathematica, and Maple can know that they are adding or quadding because they can work from the symbolic description of the behavior. Like humans, they deal with short descriptions of large things1. We can't write out all of the digits in the number 10^120. But because we can manipulate short descriptions of big things, we can answer what quss would do if bigN were 10^80. 10^80 is less than 10^120, so quss would return 5. Symbolic computation would give the same answer. But if we tried to do that with the actual numbers, we couldn't. When the thing described doesn't fit, it can't be worked on. Or, if the attempt is made, the old programming adage, Garbage In - Garbage Out, applies to humans and machines alike.

[1] We deal with infinity via short descriptions, e.g. "10 goto 10". We don't actually try to evaluate this, because we know we would get stuck if we did. We tag it "don't evaluate". If we actually need a result with these kinds of objects, we get rid of the infinity by various finite techniques.

[2] This post title refers to a prior brief mention of quss here. In that post, it suggested looking at the wiring of a device to determine what it does. In this post, we look at the behavior of the device across all of its inputs to determine what it does. But we only do that because we don't embed a rich description of each behavior in most devices. If we did, we could simply ask the device what it is doing. Then, just as with people, we'd have to correlate their behavior with their description of their behavior to see if they are acting as advertised.

On Rasmussen's "Against non-reductive physicalism"

03/09/22 04:15 PM

After presenting his thesis in the first section, that mental properties are not physical properties, nor are they grounded in physical properties, he carefully defines what he means by physical properties. Broadly, a physical property is something that can be measured. But nowhere does he define what a mental property is. This will turn out to be important, since mental property could mean something not physical that we think about, or it could mean how we think about something. I will use mental property for something non-physical that we think about and mental state to refer to the act of thinking, whether thinking about physical or mental properties.

It should be without controversy that there are more non-physical things than physical things. By some estimates there are 10^80 atoms in the universe. There are an unlimited number of numbers. We can't measure all of those numbers, since we can't put them in one-to-one correspondence with the "stuff" of the universe.

The first thing to note is that if the number of things argues against the physicality of mental states, then mental properties aren't needed, because there are more atoms in the universe than there are in the brain. If the sheer number of things argues against physical mental states then this would be sufficient to prove the claim. But as anyone who plays the piano knows, 88 keys can produce a conceptually infinite amount of music. And one need not postulate non-physicality to do so. Just hook a piano up to random number sources that vary the notes, tempo, and volume. The resulting music may not be melodious, but it will be unique.

Rasmussen presents a "construction principle" which states "for any properties, the xs, there is a mental property of thinking that the xs are physical." Here the confusion between mental property and mental state happens. The argument sneaks in the desired conclusion. After all, if this principle were true, then the counting argument wouldn't be needed. Clearly, there is a mental state when I think "my HomePod is playing Cat Stevens". But whether that mental state is physical or immaterial is what has to be shown. By saying it's a mental property then the assertion is mental states are non-physical and the rest of the proof isn't necessary. It's just proof by assertion.

Rasmussen then gives what he calls "a principle of uniformity" which says, "The divide between any two mental properties is narrower than the divide between physicality and non-physicality." To demonstrate this difference between physical and non-physical, he gives the example of a tower of Lego blocks. His claim is that as Lego block is stacked on Lego block, that both the Lego tower, and the shape of the Lego tower, remains physical. He asserts, "if (say) being a stack of n Lego blocks is a physical property, then clearly so is being a stack of n+1 Lego blocks, for any n." This is clearly false. A Lego tower of 10^90 pieces is non-physical. There aren't enough physical particles in the universe for constructing such a tower. Does the shape of the Lego tower remain physical? This is a more interesting question. A shape is a description of an arrangement of stuff. The shape of an imaginary rectangle and the shape of a physical rectangle are the same. Are descriptions physical or non-physical? To assert one or the other is to beg the question of the nature of mental states.

So we have a counting argument that isn't needed, a construction principle that begs the question, and a principle of uniformity that doesn't match experience.

Having failed to show that mental states are non-physical, in section 3 Rasmussen tries to show that mental states aren't grounded in physicality. The bulk of the proof is in his step B2: "if no member of MPROPERTIES entails any other, then some mental properties lack a physical grounding." He turns the counting argument around to claim that there is a problem of too few physical grounds for mental states. This claim is easily dismissed. First, consider words. The estimated vocabulary of an average adult speaker of English is 35,000 words. There is plenty of storage in the human brain for this. But if we don't know a word, we go to the dictionary to get a new definition and place that definition in short term reusable storage. If we use it enough so that it goes into long term storage, we may forget something to make room for it.

In the case of "infinite" things, we think of them in terms of a short fixed description of behavior, so we don't need a lot of storage for infinite things. The computer statement

Rasmussen's proof fails because the claim that there needs to be a unique physical property for each mental state doesn't stand. Much of our physical memory is reusable and we have access to external storage (books, videos, other people). In fact, as I wrote in 2015, "man is the animal that uses external storage". [2]

Since the final sections 4 and 5 aren't supported by 1, 2, and 3, they will be skipped over.

[1] See "Lazy Evaluation" for some ways to deal with infinite sequences with limited storage.

[2] "Man is the Animal...". Almost seven years later, this statement is still unique to me. Don't know why. It's obvious "to the most casual observer."

It should be without controversy that there are more non-physical things than physical things. By some estimates there are 10^80 atoms in the universe. There are an unlimited number of numbers. We can't measure all of those numbers, since we can't put them in one-to-one correspondence with the "stuff" of the universe.

The first thing to note is that if the number of things argues against the physicality of mental states, then mental properties aren't needed, because there are more atoms in the universe than there are in the brain. If the sheer number of things argues against physical mental states then this would be sufficient to prove the claim. But as anyone who plays the piano knows, 88 keys can produce a conceptually infinite amount of music. And one need not postulate non-physicality to do so. Just hook a piano up to random number sources that vary the notes, tempo, and volume. The resulting music may not be melodious, but it will be unique.

Rasmussen presents a "construction principle" which states "for any properties, the xs, there is a mental property of thinking that the xs are physical." Here the confusion between mental property and mental state happens. The argument sneaks in the desired conclusion. After all, if this principle were true, then the counting argument wouldn't be needed. Clearly, there is a mental state when I think "my HomePod is playing Cat Stevens". But whether that mental state is physical or immaterial is what has to be shown. By saying it's a mental property then the assertion is mental states are non-physical and the rest of the proof isn't necessary. It's just proof by assertion.

Rasmussen then gives what he calls "a principle of uniformity" which says, "The divide between any two mental properties is narrower than the divide between physicality and non-physicality." To demonstrate this difference between physical and non-physical, he gives the example of a tower of Lego blocks. His claim is that as Lego block is stacked on Lego block, that both the Lego tower, and the shape of the Lego tower, remains physical. He asserts, "if (say) being a stack of n Lego blocks is a physical property, then clearly so is being a stack of n+1 Lego blocks, for any n." This is clearly false. A Lego tower of 10^90 pieces is non-physical. There aren't enough physical particles in the universe for constructing such a tower. Does the shape of the Lego tower remain physical? This is a more interesting question. A shape is a description of an arrangement of stuff. The shape of an imaginary rectangle and the shape of a physical rectangle are the same. Are descriptions physical or non-physical? To assert one or the other is to beg the question of the nature of mental states.

So we have a counting argument that isn't needed, a construction principle that begs the question, and a principle of uniformity that doesn't match experience.

Having failed to show that mental states are non-physical, in section 3 Rasmussen tries to show that mental states aren't grounded in physicality. The bulk of the proof is in his step B2: "if no member of MPROPERTIES entails any other, then some mental properties lack a physical grounding." He turns the counting argument around to claim that there is a problem of too few physical grounds for mental states. This claim is easily dismissed. First, consider words. The estimated vocabulary of an average adult speaker of English is 35,000 words. There is plenty of storage in the human brain for this. But if we don't know a word, we go to the dictionary to get a new definition and place that definition in short term reusable storage. If we use it enough so that it goes into long term storage, we may forget something to make room for it.

In the case of "infinite" things, we think of them in terms of a short fixed description of behavior, so we don't need a lot of storage for infinite things. The computer statement

is a short description of an endless process. We don't actually think of the entire infinite thing, but rather finite descriptions of the behavior behind the process. [1]

10 goto 10

Rasmussen's proof fails because the claim that there needs to be a unique physical property for each mental state doesn't stand. Much of our physical memory is reusable and we have access to external storage (books, videos, other people). In fact, as I wrote in 2015, "man is the animal that uses external storage". [2]

Since the final sections 4 and 5 aren't supported by 1, 2, and 3, they will be skipped over.

[1] See "Lazy Evaluation" for some ways to deal with infinite sequences with limited storage.

[2] "Man is the Animal...". Almost seven years later, this statement is still unique to me. Don't know why. It's obvious "to the most casual observer."

On Limited Atonement

09/01/21 03:10 PM

[updated 5/9/2023 to fix link]

The scope and application of the Atonement is an issue, it seems, that is a fairly modern development. Up until the 9th century, the writings of the Church fathers showed agreement that the scope of the atonement was universal -- for everyone -- but that its effect was limited to those who believe[1]. Many (but not all) Calvinists affirm that the Atonement is limited in scope and limited in effect. And this is clearly important to some Presbyterians.

John McLeod Campbell was a Scottish minister and highly regarded Reform theologian. A number of his writings are still available on Amazon. He allegedly disagreed with the Westminster Confession of Faith regarding the doctrine of limited atonement by teaching that the Atonement was unlimited in scope, was charged with heresy, and was removed from the ministry. Campbell might have been able to raise a defense if he had had a copy of Grudem's Systematic Theology[2], where Grudem writes:

Alas for Campbell, he was born some 180 years too soon. To add insult to excommunication, as mentioned in the previous post on limited atonement, the Confession was written by a committee. And the committee consisted of members who held to both interpretations of the scope of the Atonement. The wording of section VI of chapter 3 was such that both sides could sign the confession[see also 3]. Section 3.VI of Westminster states:

I happen to agree with this. It says:

So while I agree with 3.VI, I don't agree with this commentary!

The commentary wonders how anyone could read 3.VI any other way:

I would reply that if you don't know what language would be more clear, perhaps you should talk to those who find the language opaque. Specifically adding, "Christ died only for the elect" would make the section more clear. Or "the atonement precedes God's call and guarantees election". More on this last point later.

The positive case for universal atonement can be made from two passages of scripture: Romans 5:6 and 3:23-26:

-- Romans 5:6, NRSV

-- Romans 3:23-26, NRSV

Grudem nowhere references Romans 5:6, and Romans 3:23-26 are not found in his discussion on the extent of the atonement. Berkhof [4] references neither. To me, that's a telling omission in any argument attempting to limit the scope of the atonement.

So where does the doctrine of limited atonement come from? The argument from Berkhof will be examined.

In VI.3.b, Berkhof claims that “Scripture repeatedly qualifies those for whom Christ laid down His life in such a way as to point to a very definite limitation” and points to John 10:11 & 15 as the primary proof texts. "I lay down my life for the sheep" is read as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep." Now this is an odd way to read this statement. If I say, "I give money to my children," it in no way precludes my giving money to strangers. Why Jesus' words are read this way is a mystery, but I can make two guesses.

First, the declarative statement is read as a conditional: "If I lay down my life then it is for a sheep." If read this way, then simple logic shows that this is equivalent to "if not a sheep then I do not lay down my life." [6] Voila! Limited atonement. But you can't validly turn a declarative statement into a conditional.

Second, the passage is read as if it is the act of giving money that makes someone a child. The payment is taken from the outstretched hand, the legal paperwork is completed, and the person actually becomes a part of the family. The offer guarantees the reception. But that cannot be found in this verse. It has to be found elsewhere. Berkhof makes the attempt to show this and his arguments will be addressed in turn.

Reading John as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep" has a cascade effect throughout scripture. The following passages would have to be changed. The changes are in underlined italics.

-- John 1:29, NRSV

-- 1 John 2:2, NRSV

-- Rom 5:6, NRSV

-- 2 Cor. 5:14-15, NRSV

This is not an exhaustive list of the changes that would have to be made. Yet changes of this type are what is argued. In VI.4.a, Berkhof writes:

Granted. But at some point the addition of epicycle upon epicycle turns the perspicuity of Scripture on its head. Eventually we have to say, "Enough!". Grudem as much admits this when he writes:

Having dealt with VI.3.b and VI.4.a, we next look at VI.3.c, where Berkhof writes:

Note that no Scripture is referenced to support the claim "the scope of atonement can be no wider than the scope of His intercessory prayer." Instead, the proposition is "supported" by a rhetorical question. But the answer is really simple. In John 17, Jesus prays that He would be glorified (17:1 [5]), that His disciples would be protected and united (v. 11). For those who are not yet His disciples, He calls out “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest.” [Mt. 11:28] and "Follow me" [Lk 9:59]. The Psalmist wrote:

Note the universal scope of God's love in the Psalm. All may take refuge. 2 Cor. 5:14-15, which has already been cited, likewise shows universal scope but limited effect:

If the atonement was only for the elect, it should have been "all," not "those who live" and "will live" not "might live".

In VI.3.d, a straw man argument against a slippery slope is made:

Christ died that all might be saved and creation re-made, not that all will be saved. It must not be forgotten that because of the atonement there will be a "new heavens and a new earth". [2 Peter 3:13]

VI.3.e tries to make the case that the offer guarantees reception. Berkhof writes:

He cites six passages to support this claim: Matt. 18:11; Rom. 5:10; II Cor. 5:21; Gal. 1:4; 3:13; and Eph. 1:7. The problem is that these passages don't speak to the scope of the atonement! Someone who holds to limited atonement will read these passages without discomfort, and someone who holds to unlimited atonement will also read these passages without discomfort! Try it. Read the verses. Switch sides. Read them again. If you find a problem, check your assumptions.

VI.3.f conflates two issues. For the first, Berkhof writes:

This is a straw argument. Election is conditional, based on the sovereign choice of God. "For he says to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.” So it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who shows mercy" [Rom 9:15-16].

Berkhof them claims:

He's repeating that which he is trying to prove. At this point, the argument becomes circular. Once again, the passages offered in support of this position: Rom. 2:4; Gal. 3:13,14; Eph. 1:3,4; 2:8; Phil. 1:29; and II Tim. 3:5,6 simply do not bear the weight of his case. They do not speak to the scope of the atonement. A possible explicit counter-example to Berkhof's might be 2 Peter 2:1:

This who hold to limited atonement might argue that "denying the Master who bought them" is equivalent to Peter's denial of Christ at His trial. But this is Peter writing about these false teachers and there is no hint of recognition that their denial is like his denial. One thinks of Hebrews 10:29. Perhaps the only question asked of everyone at the final judgement is, "what did you do with the blood of My Son?" Nevertheless, both sides have their explanations so this can't be considered conclusive.

Having looked at the positive case and found it wanting, Berkhof examines four objections to the doctrine of limited atonement. Reviewing the first three, VI.4.a, VI.4.b, and VI.4.c, would be redundant. But VI.4.d is important. Berkhof writes:

That is, under limited atonement, one cannot truthfully say, "Christ died for your sins." Nor, as Berkhof claims, is “the atoning work of Christ as in itself sufficient for the redemption of all men”. For it is sufficient only for the elect.

You cannot say, "well, the offer is only for the elect but, since we don't know who is and isn't elect, we can make the offer." For those who hold to the "third use of the Law," this is ignorant of what the Law says. Leviticus, chapter 4, deals with the atonement that must be made for sins committed in ignorance. "Ignorance is no excuse" is a Biblical principle. We cannot use ignorance as an excuse to do good. Under limited atonement, there is no bona fide offer of salvation to the non-elect.

[1] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 61: "Important to note here is the fact that the question of the extent of the atonement had not been argued previously, and Gottschalk’s views are important 'because it is the first extant articulation of a definite atonement in church history.'"

[2] Systematic Theology, Wayne Grudem, 1994

[3] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 23: "... some at Dort and Westminster differed over the extent question and the final canons reflect deliberate ambiguity to allow both groups to affirm and sign the canons."

[4] Systematic Theology, Louis Berkhof, 1941

[5] Note that in John 17:2, Jesus claims that He has authority over "all people". But, clearly, His authority extends only to the elect, since the atonement extends only to the elect. If the Reformed want to be consistent, then they have to actually be consistent!

[6] The contrapositive of a conditional statement is logically equivalent to the conditional statement.

The scope and application of the Atonement is an issue, it seems, that is a fairly modern development. Up until the 9th century, the writings of the Church fathers showed agreement that the scope of the atonement was universal -- for everyone -- but that its effect was limited to those who believe[1]. Many (but not all) Calvinists affirm that the Atonement is limited in scope and limited in effect. And this is clearly important to some Presbyterians.

John McLeod Campbell was a Scottish minister and highly regarded Reform theologian. A number of his writings are still available on Amazon. He allegedly disagreed with the Westminster Confession of Faith regarding the doctrine of limited atonement by teaching that the Atonement was unlimited in scope, was charged with heresy, and was removed from the ministry. Campbell might have been able to raise a defense if he had had a copy of Grudem's Systematic Theology[2], where Grudem writes:

Finally, we may ask why this matter is so important after all. Although Reformed people have sometimes made belief in particular redemption a test of doctrinal orthodoxy, it would be healthy to realize that Scripture itself never singles this out as a doctrine of major importance, nor does it once make it the subject of any explicit theological discussion. Our knowledge of the issue comes only from incidental references to it in passages whose concern is with other doctrinal or practical matters.

Alas for Campbell, he was born some 180 years too soon. To add insult to excommunication, as mentioned in the previous post on limited atonement, the Confession was written by a committee. And the committee consisted of members who held to both interpretations of the scope of the Atonement. The wording of section VI of chapter 3 was such that both sides could sign the confession[see also 3]. Section 3.VI of Westminster states:

As God has appointed the elect unto glory, so has He, by the eternal and most free purpose of His will, foreordained all the means thereunto.[12] Wherefore, they who are elected, being fallen in Adam, are redeemed by Christ,[13] are effectually called unto faith in Christ by His Spirit working in due season, are justified, adopted, sanctified,[14] and kept by His power, through faith, unto salvation.[15] Neither are any other redeemed by Christ, effectually called, justified, adopted, sanctified, and saved, but the elect only.[16]

I happen to agree with this. It says:

- God has ordained the means of salvation

- Those whom God has foreordained for salvation will be saved.

- Only those foreordained for salvation will be saved.

In this section, then, we are taught, ... ThatChrist died exclusively for the elect, and purchased redemption for them alone; in other words, that Christ made atonement only for the elect, and that in no sense did he die for the rest of the race. Our Confession first asserts, positively, that the elect are redeemed by Christ; and then, negatively, that none other are redeemed by Christ but the elect only.

So while I agree with 3.VI, I don't agree with this commentary!

The commentary wonders how anyone could read 3.VI any other way:

If this does not affirm the doctrine of particular redemption, or of a limited atonement, we know not what language could express that doctrine more explicitly.

I would reply that if you don't know what language would be more clear, perhaps you should talk to those who find the language opaque. Specifically adding, "Christ died only for the elect" would make the section more clear. Or "the atonement precedes God's call and guarantees election". More on this last point later.

The positive case for universal atonement can be made from two passages of scripture: Romans 5:6 and 3:23-26:

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for theungodly.

-- Romans 5:6, NRSV

... sinceall have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

-- Romans 3:23-26, NRSV

Grudem nowhere references Romans 5:6, and Romans 3:23-26 are not found in his discussion on the extent of the atonement. Berkhof [4] references neither. To me, that's a telling omission in any argument attempting to limit the scope of the atonement.

So where does the doctrine of limited atonement come from? The argument from Berkhof will be examined.

In VI.3.b, Berkhof claims that “Scripture repeatedly qualifies those for whom Christ laid down His life in such a way as to point to a very definite limitation” and points to John 10:11 & 15 as the primary proof texts. "I lay down my life for the sheep" is read as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep." Now this is an odd way to read this statement. If I say, "I give money to my children," it in no way precludes my giving money to strangers. Why Jesus' words are read this way is a mystery, but I can make two guesses.

First, the declarative statement is read as a conditional: "If I lay down my life then it is for a sheep." If read this way, then simple logic shows that this is equivalent to "if not a sheep then I do not lay down my life." [6] Voila! Limited atonement. But you can't validly turn a declarative statement into a conditional.

Second, the passage is read as if it is the act of giving money that makes someone a child. The payment is taken from the outstretched hand, the legal paperwork is completed, and the person actually becomes a part of the family. The offer guarantees the reception. But that cannot be found in this verse. It has to be found elsewhere. Berkhof makes the attempt to show this and his arguments will be addressed in turn.

Reading John as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep" has a cascade effect throughout scripture. The following passages would have to be changed. The changes are in underlined italics.

The next day he saw Jesus coming toward him and declared, “Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of theelect in the world!”

-- John 1:29, NRSV

and he is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of theelect in the whole world.

-- 1 John 2:2, NRSV

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for theelect ungodly.

-- Rom 5:6, NRSV

For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. And he died for allof the elect, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them.

-- 2 Cor. 5:14-15, NRSV

This is not an exhaustive list of the changes that would have to be made. Yet changes of this type are what is argued. In VI.4.a, Berkhof writes:

The objection based on these passages proceeds on the unwarranted assumption that the word “world” as used in them means “all the individuals that constitute the human race.” If this were not so, the objection based on them would have no point. But it is perfectly evident from Scripture that the term “world” has a variety of meanings...

Granted. But at some point the addition of epicycle upon epicycle turns the perspicuity of Scripture on its head. Eventually we have to say, "Enough!". Grudem as much admits this when he writes:

On the other hand, the sentence, “Christ died for all people,” is true if it means, “Christ died to make salvation available to all people” or if it means, “Christ died to bring the free offer of the gospel to all people.” In fact, this is the kind of language Scripture itself uses in passages like John 6:51; 1 Timothy 2:6; and 1 John 2:2. It really seems to be only nit-picking that creates controversies and useless disputes when Reformed people insist on being such purists in their speech that they object any time someone says that “Christ died for all people.” There are certainly acceptable ways of understanding that sentence that areconsistent with the speech of the scriptural authors themselves.

Having dealt with VI.3.b and VI.4.a, we next look at VI.3.c, where Berkhof writes:

The sacrificial work of Christ and His intercessory work are simply two different aspects of His atoning work, and therefore the scope of the one can be no wider than that of the other. ... Why should He limit His intercessory prayer, if He had actually paid the price for all?

Note that no Scripture is referenced to support the claim "the scope of atonement can be no wider than the scope of His intercessory prayer." Instead, the proposition is "supported" by a rhetorical question. But the answer is really simple. In John 17, Jesus prays that He would be glorified (17:1 [5]), that His disciples would be protected and united (v. 11). For those who are not yet His disciples, He calls out “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest.” [Mt. 11:28] and "Follow me" [Lk 9:59]. The Psalmist wrote:

Your steadfast love, O LORD, extends to the heavens, your faithfulness to the clouds. Your righteousness is like the mighty mountains, your judgments are like the great deep; you save humans and animals alike, O LORD. How precious is your steadfast love, O God! All people may take refuge in the shadow of your wings.

-- Psalms 36:5-7, NRSV

Note the universal scope of God's love in the Psalm. All may take refuge. 2 Cor. 5:14-15, which has already been cited, likewise shows universal scope but limited effect:

For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. Andhe died for all, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them.

If the atonement was only for the elect, it should have been "all," not "those who live" and "will live" not "might live".

In VI.3.d, a straw man argument against a slippery slope is made:

It should also be noted that the doctrine that Christ died for the purpose of saving all men, logically leads to absolute universalism, that is, to the doctrine that all men are actually saved.

Christ died that all might be saved and creation re-made, not that all will be saved. It must not be forgotten that because of the atonement there will be a "new heavens and a new earth". [2 Peter 3:13]

VI.3.e tries to make the case that the offer guarantees reception. Berkhof writes:

... it should be pointed out that there is an inseparable connection between the purchase and the actual bestowal of salvation.

He cites six passages to support this claim: Matt. 18:11; Rom. 5:10; II Cor. 5:21; Gal. 1:4; 3:13; and Eph. 1:7. The problem is that these passages don't speak to the scope of the atonement! Someone who holds to limited atonement will read these passages without discomfort, and someone who holds to unlimited atonement will also read these passages without discomfort! Try it. Read the verses. Switch sides. Read them again. If you find a problem, check your assumptions.

VI.3.f conflates two issues. For the first, Berkhof writes:

And if the assertion be made that the design of God and of Christ was evidently conditional, contingent on the faith and obedience of man...

This is a straw argument. Election is conditional, based on the sovereign choice of God. "For he says to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.” So it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who shows mercy" [Rom 9:15-16].

Berkhof them claims:

... the Bible clearly teaches that Christ by His death purchased faith, repentance, and all the other effects of the work of the Holy Spirit, for His people.

He's repeating that which he is trying to prove. At this point, the argument becomes circular. Once again, the passages offered in support of this position: Rom. 2:4; Gal. 3:13,14; Eph. 1:3,4; 2:8; Phil. 1:29; and II Tim. 3:5,6 simply do not bear the weight of his case. They do not speak to the scope of the atonement. A possible explicit counter-example to Berkhof's might be 2 Peter 2:1:

But false prophets also arose among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you, who will secretly bring in destructive opinions. They will evendeny the Master who bought them—bringing swift destruction on themselves.

This who hold to limited atonement might argue that "denying the Master who bought them" is equivalent to Peter's denial of Christ at His trial. But this is Peter writing about these false teachers and there is no hint of recognition that their denial is like his denial. One thinks of Hebrews 10:29. Perhaps the only question asked of everyone at the final judgement is, "what did you do with the blood of My Son?" Nevertheless, both sides have their explanations so this can't be considered conclusive.

Having looked at the positive case and found it wanting, Berkhof examines four objections to the doctrine of limited atonement. Reviewing the first three, VI.4.a, VI.4.b, and VI.4.c, would be redundant. But VI.4.d is important. Berkhof writes:

Finally, there is an objection derived from the bona fide offer of salvation

That is, under limited atonement, one cannot truthfully say, "Christ died for your sins." Nor, as Berkhof claims, is “the atoning work of Christ as in itself sufficient for the redemption of all men”. For it is sufficient only for the elect.

You cannot say, "well, the offer is only for the elect but, since we don't know who is and isn't elect, we can make the offer." For those who hold to the "third use of the Law," this is ignorant of what the Law says. Leviticus, chapter 4, deals with the atonement that must be made for sins committed in ignorance. "Ignorance is no excuse" is a Biblical principle. We cannot use ignorance as an excuse to do good. Under limited atonement, there is no bona fide offer of salvation to the non-elect.

[1] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 61: "Important to note here is the fact that the question of the extent of the atonement had not been argued previously, and Gottschalk’s views are important 'because it is the first extant articulation of a definite atonement in church history.'"

[2] Systematic Theology, Wayne Grudem, 1994

[3] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 23: "... some at Dort and Westminster differed over the extent question and the final canons reflect deliberate ambiguity to allow both groups to affirm and sign the canons."

[4] Systematic Theology, Louis Berkhof, 1941

[5] Note that in John 17:2, Jesus claims that He has authority over "all people". But, clearly, His authority extends only to the elect, since the atonement extends only to the elect. If the Reformed want to be consistent, then they have to actually be consistent!

[6] The contrapositive of a conditional statement is logically equivalent to the conditional statement.

Ravi Zacharias on Objective Morality

03/07/20 04:12 PM

In this short video (5 minutes), Ravi Zacharias is asked the question, "why are you so afraid of subjective moral reasoning?" To which Ravi replied, "do you lock your door at night?"

This is an flawed answer, simply because people don't always do what they know they should do. That is, if morals are objective, people won't always act morally1, and if morals are subjective, then people won't always act morally2. Therefore, this answer has no bearing on the question!

Ravi further states:

If morality is purely subjective then you have absolutely nothing from stopping anybody from being a subjective moralist to choose to just zing one through your forehead and say 'that's my answer.'" How do you stop that? If you're willing to say to me that moral reasoning can be purely subjective, I just say to you, "look out, you ain't seen nothing yet."

This answer fails for (at least) four reasons.

First, it's the fallacy of the "appeal to consequences." That is, the desirability of something generally has no bearing on whether or not a statement is true or false. The statement "it is true (or false) that morals are subjective" is not proved by "subjective morality isn't desirable."

Second, it requires an appeal to authority. After all, who says that "subjective morality isn't desirable?" Ravi? The listener?3 God? For an appeal to authority to have some credibility, everyone has to agree on the authority. Atheists certainly don't agree that God carries any authority.

Third, Ravi knows that governments wield the sword against "evildoers".4 "Wield the sword." "Zing one through the forehead". Same difference. When Paul wrote this, the citizens didn't get to choose the kind of government they had or what the government thought was good and evil. Paul was imprisoned and eventually executed by that government.5

Fourth, and most importantly, Ravi should know the answer to "how do you stop that?" By preaching the gospel, that's how. God pours His love into the hearts of those who believe and "love does no wrong to a neighbor."6

That this particular response does not adequately address whether morals are objective, does not prove that they are subjective. After all, there could be a better answer. One would have hoped that a renowned apologist would have had a better response.

[1] The initial course, "Introduction: First Five Lessons" in the Open Yale course Game Theory, shows where students are asked to play a game. Most of them don't know, and therefore don't use, the optimal strategy when they first play the game. But after the instructor analyzes the problem and shows them the objective answer -- the right thing to do -- some of them still don't make that choice!

[2] See Another Short Conversation...

[3] I once had a conversation with an Indian coworker. He didn't understand why the US didn't nuke Pakistan in order to take out Bin Laden. When I replied that the fallout would take out tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of his countrymen he responded, "So what? They're just surplus people." What horrified me was a desirable outcome for him.

[4] Romans 13:4.

[5] Genesis 50:20

[6] Romans 13:10.

This is an flawed answer, simply because people don't always do what they know they should do. That is, if morals are objective, people won't always act morally1, and if morals are subjective, then people won't always act morally2. Therefore, this answer has no bearing on the question!

Ravi further states:

If morality is purely subjective then you have absolutely nothing from stopping anybody from being a subjective moralist to choose to just zing one through your forehead and say 'that's my answer.'" How do you stop that? If you're willing to say to me that moral reasoning can be purely subjective, I just say to you, "look out, you ain't seen nothing yet."

This answer fails for (at least) four reasons.

First, it's the fallacy of the "appeal to consequences." That is, the desirability of something generally has no bearing on whether or not a statement is true or false. The statement "it is true (or false) that morals are subjective" is not proved by "subjective morality isn't desirable."

Second, it requires an appeal to authority. After all, who says that "subjective morality isn't desirable?" Ravi? The listener?3 God? For an appeal to authority to have some credibility, everyone has to agree on the authority. Atheists certainly don't agree that God carries any authority.

Third, Ravi knows that governments wield the sword against "evildoers".4 "Wield the sword." "Zing one through the forehead". Same difference. When Paul wrote this, the citizens didn't get to choose the kind of government they had or what the government thought was good and evil. Paul was imprisoned and eventually executed by that government.5

Fourth, and most importantly, Ravi should know the answer to "how do you stop that?" By preaching the gospel, that's how. God pours His love into the hearts of those who believe and "love does no wrong to a neighbor."6

That this particular response does not adequately address whether morals are objective, does not prove that they are subjective. After all, there could be a better answer. One would have hoped that a renowned apologist would have had a better response.

[1] The initial course, "Introduction: First Five Lessons" in the Open Yale course Game Theory, shows where students are asked to play a game. Most of them don't know, and therefore don't use, the optimal strategy when they first play the game. But after the instructor analyzes the problem and shows them the objective answer -- the right thing to do -- some of them still don't make that choice!

[2] See Another Short Conversation...

[3] I once had a conversation with an Indian coworker. He didn't understand why the US didn't nuke Pakistan in order to take out Bin Laden. When I replied that the fallout would take out tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of his countrymen he responded, "So what? They're just surplus people." What horrified me was a desirable outcome for him.

[4] Romans 13:4.

[5] Genesis 50:20

[6] Romans 13:10.

John Owen's Trilemma

01/05/20 04:16 PM

In today's adult Sunday class on the parable of the wedding banquet (Matthew 22:14), the trilemma of John Owen was mentioned as an aside. Owen tries to show the doctrine of Limited Atonement -- formulated as Christ died only for the elect -- from this argument:

I would argue that this argument fails because the correct answer is #3: Christ died for some of the sins of all men. In fact, I would propose a modified form of #3: Christ died for all but one sin of all men. This is, in fact, what Jesus Himself said in Matthew 12:31:

We might argue about what the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit entails, but I hold that it refers to unbelief, since Paul, in Romans 3:21-25, wrote:

Showing an error in an argument for something, of course, does not prove that thing and this post is not looking at the doctrine of Limited Atonement in general. However, in reviewing the doctrine of Atonement in the Westminster Confessions, I found this discussion interesting, in that it said that the Amyrauldians present at the Westminster Assembly were not hesitant to sign the Confession. That argues for some ambiguity in the wording of the Confession.

The Father imposed His wrath due unto, and the Son underwent punishment for, either:In which case it may be said:

- All the sins of all men.

- All the sins of some men, or

- Some of the sins of all men.

You answer, "Because of unbelief."

- That if the last be true, all men have some sins to answer for, and so, none are saved.

- That if the second be true, then Christ, in their stead suffered for all the sins of all the elect in the whole world, and this is the truth.

- But if the first be the case, why are not all men free from the punishment due unto their sins?

I ask, Is this unbelief a sin, or is it not? If it be, then Christ suffered the punishment due unto it, or He did not. If He did, why must that hinder them more than their other sins for which He died? If He did not, He did not die for all their sins!"

I would argue that this argument fails because the correct answer is #3: Christ died for some of the sins of all men. In fact, I would propose a modified form of #3: Christ died for all but one sin of all men. This is, in fact, what Jesus Himself said in Matthew 12:31:

Therefore I tell you, people will be forgiven for every sin and blasphemy, but blasphemy against the Spirit will not be forgiven.

We might argue about what the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit entails, but I hold that it refers to unbelief, since Paul, in Romans 3:21-25, wrote:

But now, apart from law, the righteousness of God has been disclosed, and is attested by the law and the prophets, the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ for all who believe. For there is no distinction, since all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

Showing an error in an argument for something, of course, does not prove that thing and this post is not looking at the doctrine of Limited Atonement in general. However, in reviewing the doctrine of Atonement in the Westminster Confessions, I found this discussion interesting, in that it said that the Amyrauldians present at the Westminster Assembly were not hesitant to sign the Confession. That argues for some ambiguity in the wording of the Confession.

Wright Runs Away -- Then Came Back

09/14/19 01:25 PM

Update 9/17 @ 11:15am: This morning I looked to see if there had been any more comments on the below referenced post and I saw that my comment, which had been deleted, was now present. So I retract the statement that Wright ran away. Still, if he would only attempt to show me where I'm wrong in my argument...

Over the years I've had several fruitless, yet generally polite, arguments[1] with author, philosopher, and theist John Wright. Fruitless, because neither of us is swayed by the other's arguments. I remain fully convinced that some of his arguments are wrong, even if some of his conclusions happen to be right. Polite, because we stick to the arguments.

But, yesterday, in Wright's Parable of the Adding Machine, he deleted a response that I made to him.

My initial response. His response. Here is the reply he deleted:

It isn't clear to me why Wright deleted this response. He's certainly free to do whatever he wants with his blog, but I didn't violate any of his conditions for posting. My guess is that this left him with a challenge he couldn't rebut. Wright very much wants to prove that immaterial things exist. That's easy. But he also wants to prove that they exist apart from material things. That's hard. It may be impossible to prove either way. What my response showed is that arithmetic is based on simple physical operations. Add a rock to a pail. Remove a rock from a pail. Determine if a pail is empty. Do something if a pail is empty otherwise do something else. These actions give you addition, subtraction, multiplication, and exponentiation over the non-negative integers. Attach labels to these actions and you have elementary arithmetic. Attach labels to collections of labels and you have shortcuts that hide a tremendous amount of physical activity. Wright doesn't know how to sever the ideas of math (which are basically just "potential actions," not unlike a high jumper who looks where he's going to make each step on his approach to jumping over the bar before he actually does it). This argument supports the idea that math is "matter in motion in certain patterns," which Wright very much does not want to be true.

This explains why, in a previous discussion, Wright was so opposed to the following observation about Euclidean geometry, by Marvin Jay Greenberg, from Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries:

This challenged his assertion that Euclidean geometry was purely non-physical.

Am I right as to why he deleted my post? I may never know, because he avoided the challenge.

A partial catalog of discussions with Wright:

Over the years I've had several fruitless, yet generally polite, arguments[1] with author, philosopher, and theist John Wright. Fruitless, because neither of us is swayed by the other's arguments. I remain fully convinced that some of his arguments are wrong, even if some of his conclusions happen to be right. Polite, because we stick to the arguments.

But, yesterday, in Wright's Parable of the Adding Machine, he deleted a response that I made to him.

My initial response. His response. Here is the reply he deleted:

A stopsign written in Chinese only means STOP to someone who reads Chinese.Drop me in the middle of China and I'll tell you which sign means "stop" after watching how the Chinese behave around them.

[The symbols] must follow arithmetic rules.Sure. But the rules are labels for behaviors. Show me the behaviors and I'll tell you what the symbols mean.

The behavior of the gear train is a thoughtless therefore blind and meaningless motion of bit of matter in reaction to a clerk pressing a lever.The behavior follows a pattern, a pattern which is the same as that performed with stones and pails. Since we've given labels to the latter behaviors, because the behavior of the machine matches that pattern, we can use the same labels.

... because the form of both the clerks calculation and the gears' motion share the same formSo you agree with the first sentence of the prior blockquote. Do you disagree with the second sentence? If so, why?

But the machine cannot count.It implements the successor function for a finite set of numbers. The behavior is what matters.

It is not alive.Define "alive". Is a virus alive?

The same symbols written in a different order on another part of the machine, or on a piece of paper, would have no meaning at allSure, if they can't be associated with behavior. But, just like watching Chinese behavior around a Chinese stop sign to learn what 停 means, if I could watch the behavior of whatever made the marks, I might be able to learn what they mean. Or find a Rosetta stone, which is just a shortcut for the same thing.

It isn't clear to me why Wright deleted this response. He's certainly free to do whatever he wants with his blog, but I didn't violate any of his conditions for posting. My guess is that this left him with a challenge he couldn't rebut. Wright very much wants to prove that immaterial things exist. That's easy. But he also wants to prove that they exist apart from material things. That's hard. It may be impossible to prove either way. What my response showed is that arithmetic is based on simple physical operations. Add a rock to a pail. Remove a rock from a pail. Determine if a pail is empty. Do something if a pail is empty otherwise do something else. These actions give you addition, subtraction, multiplication, and exponentiation over the non-negative integers. Attach labels to these actions and you have elementary arithmetic. Attach labels to collections of labels and you have shortcuts that hide a tremendous amount of physical activity. Wright doesn't know how to sever the ideas of math (which are basically just "potential actions," not unlike a high jumper who looks where he's going to make each step on his approach to jumping over the bar before he actually does it). This argument supports the idea that math is "matter in motion in certain patterns," which Wright very much does not want to be true.

This explains why, in a previous discussion, Wright was so opposed to the following observation about Euclidean geometry, by Marvin Jay Greenberg, from Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries:

Ancient geometry was actually a collection of rule-of-thumb procedures arrived at through experimentation, observation of analogies, guessing, and occasional flashes of intuition. In short, it was an empirical subject in which approximate answers were usually sufficient for practical purposes.

This challenged his assertion that Euclidean geometry was purely non-physical.

Am I right as to why he deleted my post? I may never know, because he avoided the challenge.

A partial catalog of discussions with Wright:

Date Title 9/8/2010 Dialog With An Adding Machine 1/26/2011 Materialism, Theism, and Information 3/24/2011 Taking Ideas Seriously 4/16/2011 Bad Arguments Against Materialism 5/8/2012 My Instinct is to say the Morality is not Instinctive 4/29/2014 The Cosmic Chessboard, or, ONCE MORE FOR OLD TIMES SAKE! 12/15/2014 When Wright Is Wrong 5/17/2015 The Notorious Meat Robot Letters – Expanded! 5/16/2015 Man Is The Animal... 5/8/2019 No Metaphysics, No Physics

The Trinity by Dale Tuggy : A Critique

11/24/17 05:09 PM

[updated 8/22/19 to correct spelling of "Mermin"]

A Unitarian friend of mine loaned me this book as part of our ongoing debate about the nature of God. The Introduction isn't bad, but it contains the seeds of two problems that the author will have to address when discussing the alleged shortcomings of the doctrine of the Trinity. The first is the actual Biblical evidence. Anti-Trinitarians, in my experience, tend to focus on the writings of Church Fathers, creedal statements and their origins, political infighting, and so on. Indeed, the introduction beings with:

A Unitarian friend of mine loaned me this book as part of our ongoing debate about the nature of God. The Introduction isn't bad, but it contains the seeds of two problems that the author will have to address when discussing the alleged shortcomings of the doctrine of the Trinity. The first is the actual Biblical evidence. Anti-Trinitarians, in my experience, tend to focus on the writings of Church Fathers, creedal statements and their origins, political infighting, and so on. Indeed, the introduction beings with:

Read More...

Read More...

Dr. Larycia Hawkins and Wheaton College

01/09/16 05:01 PM

[Updated 9/18/19 to use a link to an archived version of the Wheaton FAQ concerning Dr. Hawkins, and to remove a possible ambiguity from my initial paragraph.]

Wheaton College has initiated termination proceedings against tenured professor Dr. Larycia Hawkins who has been a faculty member since 2007 and who received tenure in 2013. Wheaton is taking this action because of her statement that Christians and Muslims worship the same God. Apparently, this idea is counter to the Wheaton statement of faith. I note, for the record, that there is no explicit sentence in their statement of faith regarding which groups worship which God. Furthermore, in a FAQ published by Wheaton, question 7 asks "Is it true that Christians and Muslims worship the same God?" Wheaton lists doctrines which are distinctive to Christianity but are denied by Islam. But, note carefully, that Wheaton doesn't specifically answer the question with a simple "yes" or "no." For if they did, a bright undergraduate would then ask, "given this criteria, do Christians and Jews worship the same God?" I suspect Wheaton doesn't want that question to be asked.

But I digress. On December 17, 2015, Dr. Hawkins wrote to Wheaton in which she explained the reasons for her position as well as her personal statement of faith.

Opinion is of course, split, concerning the question of whether or not Muslims and Christians worship the same God. Dr. Edward Feser addressed the issue in the affirmative here. Vox Day, and many of his readers, answered in the negative, here. Last night at dinner, my wife initially said, "no"; this morning at breakfast, my reform seminary graduate friend Steve immediately said "yes."

I think Wheaton College is about to fall into a pit that they just don't yet see.

Let us consider two cases, one from literature and one from science. For literature, consider the two authors C. S. Lewis, who wrote the Narnia Chronicles, and Gene Roddenberry, who wrote Star Trek. Now suppose that there are two groups of people. One group asserts that humans owe their existence to having entered our world through a gate from Narnia. This is, of course, backwards from the way Lewis told the story in "The Magicians Nephew" — but bear with me. The other group asserts that humans originally came from the planet Vulcan. And again, in the original lore, it was the Romulans who were the offshoots of the Vulcans — just let me run with this. The only thing these two groups have in common is the idea that we came from somewhere else. Everything else is completely different and they are completely different because they are solely products of human imagination. Fans may argue the differences between Narnia and Star Trek, or Battlestar Galactica and Babylon 5. No one takes them seriously (except themselves) because we know it's "just fiction." It doesn't make sense to argue about which imaginary world is right.

Now consider the realm of science which attempts to discern how Nature works. We believe that this Nature exists independently of us. It is not a product of our imagination. At one time, science advanced the theory of the aether which was thought to be necessary for the propagation of light. But the Michelson-Morley experiments showed that this theory was wrong. Improvements to experiments to test Bell's inequality have shown that local realism isn't a viable theory of quantum mechanics. No discussion of misguided and incorrect scientific theories would be complete without mention of the famous phrase, attributed to Wolfgang Pauli, "That is not only not right, it is not even wrong." And let us not forget to mention String Theory, where some scientists say that not only is it not good science, it isn't science at all; while other scientists claim that it's really the only theory which can unite relativity and quantum mechanics. (As always, Lubos Motl is entertaining and instructive to read when it comes to String Theory).

In this case, we do not say, "you aren't studying the same nature we are." We say, "your understanding of nature is flawed."

If Wheaton continues down this path with Dr. Hawkins, whether they know it or not, they will be giving aid and comfort to those who claim that God is purely imaginary. And if they do that, then they are the ones who have betrayed their statement of faith.

Wheaton College has initiated termination proceedings against tenured professor Dr. Larycia Hawkins who has been a faculty member since 2007 and who received tenure in 2013. Wheaton is taking this action because of her statement that Christians and Muslims worship the same God. Apparently, this idea is counter to the Wheaton statement of faith. I note, for the record, that there is no explicit sentence in their statement of faith regarding which groups worship which God. Furthermore, in a FAQ published by Wheaton, question 7 asks "Is it true that Christians and Muslims worship the same God?" Wheaton lists doctrines which are distinctive to Christianity but are denied by Islam. But, note carefully, that Wheaton doesn't specifically answer the question with a simple "yes" or "no." For if they did, a bright undergraduate would then ask, "given this criteria, do Christians and Jews worship the same God?" I suspect Wheaton doesn't want that question to be asked.

But I digress. On December 17, 2015, Dr. Hawkins wrote to Wheaton in which she explained the reasons for her position as well as her personal statement of faith.

Opinion is of course, split, concerning the question of whether or not Muslims and Christians worship the same God. Dr. Edward Feser addressed the issue in the affirmative here. Vox Day, and many of his readers, answered in the negative, here. Last night at dinner, my wife initially said, "no"; this morning at breakfast, my reform seminary graduate friend Steve immediately said "yes."

I think Wheaton College is about to fall into a pit that they just don't yet see.

Let us consider two cases, one from literature and one from science. For literature, consider the two authors C. S. Lewis, who wrote the Narnia Chronicles, and Gene Roddenberry, who wrote Star Trek. Now suppose that there are two groups of people. One group asserts that humans owe their existence to having entered our world through a gate from Narnia. This is, of course, backwards from the way Lewis told the story in "The Magicians Nephew" — but bear with me. The other group asserts that humans originally came from the planet Vulcan. And again, in the original lore, it was the Romulans who were the offshoots of the Vulcans — just let me run with this. The only thing these two groups have in common is the idea that we came from somewhere else. Everything else is completely different and they are completely different because they are solely products of human imagination. Fans may argue the differences between Narnia and Star Trek, or Battlestar Galactica and Babylon 5. No one takes them seriously (except themselves) because we know it's "just fiction." It doesn't make sense to argue about which imaginary world is right.

Now consider the realm of science which attempts to discern how Nature works. We believe that this Nature exists independently of us. It is not a product of our imagination. At one time, science advanced the theory of the aether which was thought to be necessary for the propagation of light. But the Michelson-Morley experiments showed that this theory was wrong. Improvements to experiments to test Bell's inequality have shown that local realism isn't a viable theory of quantum mechanics. No discussion of misguided and incorrect scientific theories would be complete without mention of the famous phrase, attributed to Wolfgang Pauli, "That is not only not right, it is not even wrong." And let us not forget to mention String Theory, where some scientists say that not only is it not good science, it isn't science at all; while other scientists claim that it's really the only theory which can unite relativity and quantum mechanics. (As always, Lubos Motl is entertaining and instructive to read when it comes to String Theory).

In this case, we do not say, "you aren't studying the same nature we are." We say, "your understanding of nature is flawed."

If Wheaton continues down this path with Dr. Hawkins, whether they know it or not, they will be giving aid and comfort to those who claim that God is purely imaginary. And if they do that, then they are the ones who have betrayed their statement of faith.

Feser's Philosophy of Mind, #3

10/26/15 09:15 PM

This chapter deals with materialistic views of mind, namely that reality, and therefore the mind:

I note, purely in passing, that the second sentence doesn't necessarily follow from the first. In any case, Feser then proceeds to argue that it is difficult to see how things like cultural conventions, for example, are:

and

Here is how it's done. We have no problem understanding that there are quarks and electrons. We have no problem understanding that quarks combine to form protons and neutrons, and that protons, neutrons, and electrons form atoms. Atoms form trees and stars, bacteria and brains.