The Universe Inside

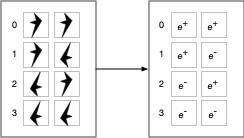

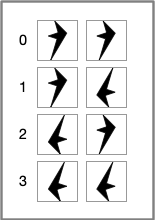

Let us replace distinguishable objects with objects that distinguish themselves:

Then the physical operation that determines if two elements are equal is:

As shown in the previous post, e+ (the positron and its behavior) and e- (the electron and its behavior) are the behaviors assigned to the labels "true" and "false". One could swap e+ and e-. The physical system would still exhibit consistent logical behavior. In any case, this physical operation answers the question "are we the same?", "Is this me?", because these fundamental particles are self-identifying.

From this we see that logical behavior - the selection of one item from a set of two - is fully determined behavior.

In contrast to logic, nature features fully undetermined behavior where a selection is made from a group at random. The double-slit experiment shows the random behavior of light as it travels through a barrier with two slits and lands somewhere on a detector.

In between these two options, there is partially determined, or goal directed behavior where selections are made from a set of choices that lead to a desired state. It is a mixture of determined and undetermined behavior. This is where the problem of teleology comes in. To us, moving toward a goal state indicates purpose. But what if the goal is chosen at random? Another complication is that, while random events are unpredictable, sequences of random events have predictable behavior. Over time, a sequence of random events with tend to its expected value. We are faced with having to decide if randomness indicates no purpose or hidden purpose, agency or no agency.

In this post, from 2012, I made a claim about a relationship between software and hardware. In the post, "On the Undecidability of Materialism vs. Idealism", I presented an argument using the Lambda Calculus to show how software and hardware are so entwined that you can't physically take them apart. This low-level view of nature reinforces these ideas. All logical operations are physical (all software is hardware). Not all physical operations are logical (not all hardware is software). Computing is behavior and the behavior of the elementary particles cannot be separated from the particles themselves. If we're going to choose between idealism and physicalism, it must be based on a coin flip2.

If computers are built of logic "circuits" then computer behavior ought to be fully determined. But when we add peripherals to the system and inject random behavior (either in the program itself, or from external sources), we get non-logical behavior in addition to logic. If a computer is a microcosm of the brain, the brain is a microcosm of the universe.

[1] Quarks have fractional charge, but quarks aren't found outside the atomic nucleus. The strong nuclear force keeps them together. Electrons and positrons are elementary particles.

[2] Dualism might be the only remaining choice, but I think that dualism can't be right. That's a post for another day.

Electric Charge, Truth, and Self-Awareness

John 18:38, NRSV

What is truth?

— Pilate,

To say of what is that it is not, or of what is not that it is, is false, while to say of

what is that it is, and of what is not that it is not, is true.

— Aristotle

"The truth points to itself."

"What?"

"The truth points to itself."

"I do not understand."

"You will."

— Kosh and Delenn in Babylon 5:"In the Beginning"

The one quote that I want, but can no longer find, is to the effect that philosophers don't really know what truth is. Introductions to the philosophy of truth (e.g. here) make for fascinating reading. I claim that the philosophers can't reach agreement because they aren't trying to build a self-aware creature. Were they to attempt it, they might reason something like the following.

Aristotle's definition of truth is clumsy. It simplifies to:If true then [say] true is true.

In hindsight, this isn't a totally terrible definition. It combines the behavior (say "true") with the behavior ("truth leads to truth"). But it's still circular. "True ... is true" doesn't tell us what truth is, so it's useless for building something.

Still, this formulation anticipated a definition of truth in computer programming languages by some 1,700 years:if true then truth-action else false-action

"True" is a special symbol that is given the special meaning of truth. In Lisp, t is true and nil is false. In FORTRAN, .true. is true and .false. is false. Python uses True and False. And so on. But this still doesn't tell you what truth is other than it is a special symbol that can be used for making selections.

Looking at how "true" is defined in the Lambda Calculus provides a critical clue. Considering the Lambda Calculus is important, because it describes all computation in terms of behaviors (denoted by the special symbols λ, ., (, ), and blank) and meaningless symbols. There is no special symbol for "true".def true = λx.λy.x

What this means is that "true" is a function of two objects, x and y and it returns the first object x. Truth is a behavior that can be used as a property. That is, this behavior can be attached to other symbols. It is the behavior that selects true things and rejects false things. False has symmetric behavior. It selects false things and rejects true things. So we've advanced from a special symbol to a behavior. But we aren't yet done.

The simplest if-then statement is:if true then true else false

Truth is the behavior that selects itself. So we've derived the basis for the quote from Babylon 5, above. But we need to take one more step. Fundamental to the Lambda Calculus is the ability to distinguish between symbols. It is a behavior that is assumed by the Lambda calculus, one that doesn't have a special symbol like λ, ., (, ), and space to denote the behavior of distinguishing between symbols.

So consider a Lambda Calculus with two symbols:

And so, we find that truth is the ability to recognize self and select similar self-recognizing things.

And so, we find that electric charge gives us the laws of thought and truth, all in one force.

On Limited Atonement

The scope and application of the Atonement is an issue, it seems, that is a fairly modern development. Up until the 9th century, the writings of the Church fathers showed agreement that the scope of the atonement was universal -- for everyone -- but that its effect was limited to those who believe[1]. Many (but not all) Calvinists affirm that the Atonement is limited in scope and limited in effect. And this is clearly important to some Presbyterians.

John McLeod Campbell was a Scottish minister and highly regarded Reform theologian. A number of his writings are still available on Amazon. He allegedly disagreed with the Westminster Confession of Faith regarding the doctrine of limited atonement by teaching that the Atonement was unlimited in scope, was charged with heresy, and was removed from the ministry. Campbell might have been able to raise a defense if he had had a copy of Grudem's Systematic Theology[2], where Grudem writes:

Finally, we may ask why this matter is so important after all. Although Reformed people have sometimes made belief in particular redemption a test of doctrinal orthodoxy, it would be healthy to realize that Scripture itself never singles this out as a doctrine of major importance, nor does it once make it the subject of any explicit theological discussion. Our knowledge of the issue comes only from incidental references to it in passages whose concern is with other doctrinal or practical matters.

Alas for Campbell, he was born some 180 years too soon. To add insult to excommunication, as mentioned in the previous post on limited atonement, the Confession was written by a committee. And the committee consisted of members who held to both interpretations of the scope of the Atonement. The wording of section VI of chapter 3 was such that both sides could sign the confession[see also 3]. Section 3.VI of Westminster states:

As God has appointed the elect unto glory, so has He, by the eternal and most free purpose of His will, foreordained all the means thereunto.[12] Wherefore, they who are elected, being fallen in Adam, are redeemed by Christ,[13] are effectually called unto faith in Christ by His Spirit working in due season, are justified, adopted, sanctified,[14] and kept by His power, through faith, unto salvation.[15] Neither are any other redeemed by Christ, effectually called, justified, adopted, sanctified, and saved, but the elect only.[16]

I happen to agree with this. It says:

- God has ordained the means of salvation

- Those whom God has foreordained for salvation will be saved.

- Only those foreordained for salvation will be saved.

In this section, then, we are taught, ... ThatChrist died exclusively for the elect, and purchased redemption for them alone; in other words, that Christ made atonement only for the elect, and that in no sense did he die for the rest of the race. Our Confession first asserts, positively, that the elect are redeemed by Christ; and then, negatively, that none other are redeemed by Christ but the elect only.

So while I agree with 3.VI, I don't agree with this commentary!

The commentary wonders how anyone could read 3.VI any other way:

If this does not affirm the doctrine of particular redemption, or of a limited atonement, we know not what language could express that doctrine more explicitly.

I would reply that if you don't know what language would be more clear, perhaps you should talk to those who find the language opaque. Specifically adding, "Christ died only for the elect" would make the section more clear. Or "the atonement precedes God's call and guarantees election". More on this last point later.

The positive case for universal atonement can be made from two passages of scripture: Romans 5:6 and 3:23-26:

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for theungodly.

-- Romans 5:6, NRSV

... sinceall have sinned and fall short of the glory of God; they are now justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement by his blood, effective through faith.

-- Romans 3:23-26, NRSV

Grudem nowhere references Romans 5:6, and Romans 3:23-26 are not found in his discussion on the extent of the atonement. Berkhof [4] references neither. To me, that's a telling omission in any argument attempting to limit the scope of the atonement.

So where does the doctrine of limited atonement come from? The argument from Berkhof will be examined.

In VI.3.b, Berkhof claims that “Scripture repeatedly qualifies those for whom Christ laid down His life in such a way as to point to a very definite limitation” and points to John 10:11 & 15 as the primary proof texts. "I lay down my life for the sheep" is read as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep." Now this is an odd way to read this statement. If I say, "I give money to my children," it in no way precludes my giving money to strangers. Why Jesus' words are read this way is a mystery, but I can make two guesses.

First, the declarative statement is read as a conditional: "If I lay down my life then it is for a sheep." If read this way, then simple logic shows that this is equivalent to "if not a sheep then I do not lay down my life." [6] Voila! Limited atonement. But you can't validly turn a declarative statement into a conditional.

Second, the passage is read as if it is the act of giving money that makes someone a child. The payment is taken from the outstretched hand, the legal paperwork is completed, and the person actually becomes a part of the family. The offer guarantees the reception. But that cannot be found in this verse. It has to be found elsewhere. Berkhof makes the attempt to show this and his arguments will be addressed in turn.

Reading John as if Jesus said, "I lay down my life only for the sheep" has a cascade effect throughout scripture. The following passages would have to be changed. The changes are in underlined italics.

The next day he saw Jesus coming toward him and declared, “Here is the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of theelect in the world!”

-- John 1:29, NRSV

and he is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of theelect in the whole world.

-- 1 John 2:2, NRSV

For while we were still weak, at the right time Christ died for theelect ungodly.

-- Rom 5:6, NRSV

For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. And he died for allof the elect, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them.

-- 2 Cor. 5:14-15, NRSV

This is not an exhaustive list of the changes that would have to be made. Yet changes of this type are what is argued. In VI.4.a, Berkhof writes:

The objection based on these passages proceeds on the unwarranted assumption that the word “world” as used in them means “all the individuals that constitute the human race.” If this were not so, the objection based on them would have no point. But it is perfectly evident from Scripture that the term “world” has a variety of meanings...

Granted. But at some point the addition of epicycle upon epicycle turns the perspicuity of Scripture on its head. Eventually we have to say, "Enough!". Grudem as much admits this when he writes:

On the other hand, the sentence, “Christ died for all people,” is true if it means, “Christ died to make salvation available to all people” or if it means, “Christ died to bring the free offer of the gospel to all people.” In fact, this is the kind of language Scripture itself uses in passages like John 6:51; 1 Timothy 2:6; and 1 John 2:2. It really seems to be only nit-picking that creates controversies and useless disputes when Reformed people insist on being such purists in their speech that they object any time someone says that “Christ died for all people.” There are certainly acceptable ways of understanding that sentence that areconsistent with the speech of the scriptural authors themselves.

Having dealt with VI.3.b and VI.4.a, we next look at VI.3.c, where Berkhof writes:

The sacrificial work of Christ and His intercessory work are simply two different aspects of His atoning work, and therefore the scope of the one can be no wider than that of the other. ... Why should He limit His intercessory prayer, if He had actually paid the price for all?

Note that no Scripture is referenced to support the claim "the scope of atonement can be no wider than the scope of His intercessory prayer." Instead, the proposition is "supported" by a rhetorical question. But the answer is really simple. In John 17, Jesus prays that He would be glorified (17:1 [5]), that His disciples would be protected and united (v. 11). For those who are not yet His disciples, He calls out “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest.” [Mt. 11:28] and "Follow me" [Lk 9:59]. The Psalmist wrote:

Your steadfast love, O LORD, extends to the heavens, your faithfulness to the clouds. Your righteousness is like the mighty mountains, your judgments are like the great deep; you save humans and animals alike, O LORD. How precious is your steadfast love, O God! All people may take refuge in the shadow of your wings.

-- Psalms 36:5-7, NRSV

Note the universal scope of God's love in the Psalm. All may take refuge. 2 Cor. 5:14-15, which has already been cited, likewise shows universal scope but limited effect:

For the love of Christ urges us on, because we are convinced that one has died for all; therefore all have died. Andhe died for all, so that those who live might live no longer for themselves, but for him who died and was raised for them.

If the atonement was only for the elect, it should have been "all," not "those who live" and "will live" not "might live".

In VI.3.d, a straw man argument against a slippery slope is made:

It should also be noted that the doctrine that Christ died for the purpose of saving all men, logically leads to absolute universalism, that is, to the doctrine that all men are actually saved.

Christ died that all might be saved and creation re-made, not that all will be saved. It must not be forgotten that because of the atonement there will be a "new heavens and a new earth". [2 Peter 3:13]

VI.3.e tries to make the case that the offer guarantees reception. Berkhof writes:

... it should be pointed out that there is an inseparable connection between the purchase and the actual bestowal of salvation.

He cites six passages to support this claim: Matt. 18:11; Rom. 5:10; II Cor. 5:21; Gal. 1:4; 3:13; and Eph. 1:7. The problem is that these passages don't speak to the scope of the atonement! Someone who holds to limited atonement will read these passages without discomfort, and someone who holds to unlimited atonement will also read these passages without discomfort! Try it. Read the verses. Switch sides. Read them again. If you find a problem, check your assumptions.

VI.3.f conflates two issues. For the first, Berkhof writes:

And if the assertion be made that the design of God and of Christ was evidently conditional, contingent on the faith and obedience of man...

This is a straw argument. Election is conditional, based on the sovereign choice of God. "For he says to Moses, “I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.” So it depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who shows mercy" [Rom 9:15-16].

Berkhof them claims:

... the Bible clearly teaches that Christ by His death purchased faith, repentance, and all the other effects of the work of the Holy Spirit, for His people.

He's repeating that which he is trying to prove. At this point, the argument becomes circular. Once again, the passages offered in support of this position: Rom. 2:4; Gal. 3:13,14; Eph. 1:3,4; 2:8; Phil. 1:29; and II Tim. 3:5,6 simply do not bear the weight of his case. They do not speak to the scope of the atonement. A possible explicit counter-example to Berkhof's might be 2 Peter 2:1:

But false prophets also arose among the people, just as there will be false teachers among you, who will secretly bring in destructive opinions. They will evendeny the Master who bought them—bringing swift destruction on themselves.

This who hold to limited atonement might argue that "denying the Master who bought them" is equivalent to Peter's denial of Christ at His trial. But this is Peter writing about these false teachers and there is no hint of recognition that their denial is like his denial. One thinks of Hebrews 10:29. Perhaps the only question asked of everyone at the final judgement is, "what did you do with the blood of My Son?" Nevertheless, both sides have their explanations so this can't be considered conclusive.

Having looked at the positive case and found it wanting, Berkhof examines four objections to the doctrine of limited atonement. Reviewing the first three, VI.4.a, VI.4.b, and VI.4.c, would be redundant. But VI.4.d is important. Berkhof writes:

Finally, there is an objection derived from the bona fide offer of salvation

That is, under limited atonement, one cannot truthfully say, "Christ died for your sins." Nor, as Berkhof claims, is “the atoning work of Christ as in itself sufficient for the redemption of all men”. For it is sufficient only for the elect.

You cannot say, "well, the offer is only for the elect but, since we don't know who is and isn't elect, we can make the offer." For those who hold to the "third use of the Law," this is ignorant of what the Law says. Leviticus, chapter 4, deals with the atonement that must be made for sins committed in ignorance. "Ignorance is no excuse" is a Biblical principle. We cannot use ignorance as an excuse to do good. Under limited atonement, there is no bona fide offer of salvation to the non-elect.

[1] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 61: "Important to note here is the fact that the question of the extent of the atonement had not been argued previously, and Gottschalk’s views are important 'because it is the first extant articulation of a definite atonement in church history.'"

[2] Systematic Theology, Wayne Grudem, 1994

[3] The Extent of the Atonement, David L. Allen, pg. 23: "... some at Dort and Westminster differed over the extent question and the final canons reflect deliberate ambiguity to allow both groups to affirm and sign the canons."

[4] Systematic Theology, Louis Berkhof, 1941

[5] Note that in John 17:2, Jesus claims that He has authority over "all people". But, clearly, His authority extends only to the elect, since the atonement extends only to the elect. If the Reformed want to be consistent, then they have to actually be consistent!

[6] The contrapositive of a conditional statement is logically equivalent to the conditional statement.